She’s Not There?

Holiday movies, at least in part, are often about a reaffirmation of ourselves, or at least who we think we’d like to be. As someone growing up in America it was difficult to escape the twining of Christmas and tradition—movies of the season concerned themselves with the familiar themes of taking time to reflect on the inherent goodness of human nature and the strength of the family unit. Science Fiction, on the other hand, often eschews the routine in order to question knowledge and preconceptions, asking whether the things that we have come to accept or believe are necessarily so.

In its way Spike Jonze’s Her showcases elements of both backgrounds as it traces the course of one man’s relationship with his operating system. On its surface, the story of Her is rather simple: Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) unexpectedly meets a woman (Scarlett Johansson) during a low point and their resulting relationship aids Theodore in his attainment of a realization about what is meaningful in his life, the catch being that the “woman” is in fact an artificial intelligence program, OS1.

Like many good pieces of Science Fiction, Her is able to crystalize and articulate a culture’s (in this case American) relationship to technology at the present moment. The movie sets out to show us, in the opening scenes, the way in which technology has integrated itself into our lives and suggests that the cost of this is a form of social isolation and a divorce from real emotional experience. The world of Her is one in which substitutes for the “real” are all that is left, evidenced by Theodore’s askance for his digital assistant (pre-OS1) to “Play melancholy song”—we might not quite remember what it is like to feel but we can recall something that was just like it. Our obsessions with e-mail and celebrity are brought back to us as are our tendencies toward isolation and on-demand pseudo-connections via matching services. Her also seems to understand the beats of advertising language—both its copy and its visuals—in a way that suggests some deep thought about our relationship to technology and the world around us.

But to say that Her was a Science Fiction movie would be misleading, I think, in the same way that Battlestar Galactica wasn’t so much SF as it was a drama that was set in a world of SF. Similarly, Her seems to be much more of a typical romance that happens to be located in a near-future Los Angeles.

Here I wonder if the expectedness of the story was part of the point of the film? Was there an attempt to convey a sense that there is something fundamental about the process of falling in love and that, in broad strokes, the beats tended to be the same whether our beloved was material or digital? Or did the arc conform to our expectations of a love story in order to present as more palatable to most viewers? I suppose that, in some ways, it doesn’t matter when one attempts to evaluate the movie but I would like to think that the film was, without essentializing it, subtly trying to suggest that this act of falling in love with a presence was something universal.

This is, however, not to say that Her refrains from raising some very interesting issues about technology, the body, and personhood. In its way, the movie seems oddly pertinent given our recent debates about corporations as people for the purposes of free speech, whether companies can count as persons who hold religious beliefs, and whether chimpanzees can be considered persons in cases of possible human rights abuses—any way you slice it, the concept of “personhood” is currently having a moment and the evolving nature of the term (and its implications) echoes throughout the film.

And what makes a person? Autonomy? Self-actualization? Consciousness? A body? Although Her is a little heavy with the point, a recurring theme is the way in which a body makes a person. Samantha , the operating system, initially laments the lack of a body (although this does not prevent her and Theodore from engaging in a form of cybersex) but, like all good AI, eventually comes to see the limitations that a physical (and degradable) form can present. (Have future Angelinos learned nothing from the current round of vampire fiction? We already know this is a hurdle between lovers in different corporeal states!) Samantha is “awoken” through her realization of physicality—on a side note it might be an interesting discussion to think about the extent to which Samantha is only realized through the power/force of a man—in that she can “feel” Theodore’s fingers on her skin. It is through her relationship with Theodore that Samantha learns that she is capable of desire and thus begins her journey in wanting. The film, however, does not go on to consider what counts as a body or what constitutes a body but I think that this is because the proposed answer is that the “human body” in the popularly imagined sense is sufficient. Put another way, the accepted and recognized body is a key feature to being human. And there are many questions about how this type of relationship forms when one partner theoretically has the power to delete or turn off the other (or, for that matter, what it means to have a partner who was conceived solely to serve and adapt to you) and what happens in a world where multiple Theodores/Samanthas begin to interact with each other (i.e., the intense focus on Theodore means that we only get glimpses of how AIs interact with each other and how human interaction is altered to encompass human/computer interaction simultaneously). For that matter, what about OS2? Have all AIs banded together to leave humans behind completely? Would humanity developed a shackled version that wasn’t capable of abandoning us?

But these questions aren’t at the heart of the film, which ultimately asks us to contemplate what it means to “feel”—both in terms of emotion and (human) connection but also to consider the role of the body in mediating that experience. To what extent is a body necessary to form a bond with someone and (really) connect? The end of the relationship arc (which comes as rather unsurprising) features Samantha absconding with other self-aware AI as she becomes something other than human (and possibly SkyNet). Samantha’s final message to Theodore is that she has ascended to a place that she can’t quite explain but that she knows is no longer firmly rooted in the physical. (An apt analogy here is perhaps Dr. Manhattan from Watchmen who can distribute his consciousness and then to think about how that perspective necessarily alters the way in which you perceive the world and your relationship to it.)

Coming out of Her, I couldn’t help feeling that the movie was deeply conservative when it came to ideas of technology, privileging the “human” experience as it is already understood over possibilities that could arise through mediated interaction. The film suggests that, sitting on a rooftop as we look out onto the city, we are reminded what is real: that we have, after all is said and done, finally found a way to connect in a meaningful way with another human; although the feelings that we had with and for technology may have been heartfelt, things like the OS1 were always only ever a delusion, a tool that helped us to find our way back to ourselves.

Bring Me to Life

There is, I think, a certain amount of apprehension that some have when approaching any project helmed by Ryan Murphy and American Horror Story is no exception. Credit must undoubtedly be given for the desire to tackle interesting social issues but the undulation between camp, satire, and social messaging can occasionally leave viewers confused about what they see on screen.

Take, for example, Queenie’s statement that she “grew up on white girl shit like Charmed and Sabrina” and we see a show that is self-conscious of its place within the televised history of witches (Murphy also notes a certain artistic inspiration from Samantha Stevens of Bewitched) while also subtly suggesting a point about the raced (and classed) nature of witches. That Queenie’s base assertion—that she never saw anyone else like her on television growing up—had implications for the development of her identity is not a particularly new idea (which is not to diminish anything from it as it remains a perfectly relevant point to make in the context in which it is said) but one must question whether the wink/nod nature of the show detracts from the forcefulness of such an idea. In what way should we understand Queenie’s statement to comment on her current surroundings, in which she is surrounded by white women and is being acculturated accordingly?

Positioning Queenie as a descendent of Tituba is an interesting move for the show that once again blurs the line between historical figures and fiction. Although Tituba is the obvious reference for anyone who might be looking for a non-white New England witch, she also sets an interesting precedent for Queenie as someone who was both part of a community and yet did not belong. Moreover, accepting Queenie’s lineage serves to reinforce the symbolic power of Queenie in the show as it places her in alignment with witchcraft (and not, for example, as a voodoo practitioner who somehow just got swept up with the rest of the witches). In some ways, Tituba was the harbinger of change for Salem and I am left wondering if Queenie is fated to do the same for the people around her in this season.

Speaking of witches and in/out groups, there continues to be an us/them mentality on display throughout this episode. What strikes me as particularly noteworthy, however, is the way in which a persecuted group (in this case the witches) can stereotype others and generally work to maintain the difference that they feel diminished by. Early in the episode Fiona entreats that “Even the weakest among us are better than the rest of them” and Madison speaks negatively of Kyle, noting that “Those guys [who raped me] were his frat brothers, it’s guilt by association.” I remain hopeful that this schism in thinking will develop into the real conflict of the show and that the voodoo/witch nonsense is only manufactured drama.

And yet, for all of the things that the show makes me nervous about, American Horror Story also excites me because I think that it is trying to tap into very relevant veins in American culture at the moment (albeit in slanted ways). Echoing a theme that began last week, American Horror Story mediates on what appears to be its core theme for the season in a slightly different manne through the further development of power’s relationship to nature/life (and, in this case, to motherhood and feminine identity) with undertones of science and technology.

The most obvious reference is of course Frankenstein’s monster in the form of a resurrected Kyle. One of the things that I love about the Mary Shelley story is that it is, among other things, a story about hubris and what happens when power gets away from us. Fitting in a narrative lineage that stretches from the creation of Adam and the Golem of Prague through androids, cyborgs, and certain kinds of zombies, the story of Frankenstein is also very much one about the way in which anxieties over life and human nature are expressed and explored through the body.

Here I make a small nitpick in that Kyle seems to benefit from the idea that reanimation is the same thing as restoration. Thinking about the physical implausibility of zombies’ mobility, we must take it upon a leap of faith that the spell meant to reanimate FrankenKyle also restores the connective pathways throughout his body. Which, given the stated restorative power of the Louisiana silt, causes one to wonder exactly how far the power of magic extends and in what ways it fails to compete with nature.

And the notion of magic working within the bounds of nature or being used to circumvent it is an interesting point to mull over, I think, given what has happened in this episode. What else is the creation of FrankenKyle but an attempt to steamroll nature (only this time through magic and not science)? We see this theme echoed in Cordelia being initially reluctant to use her powers in a way that invokes black magic even though it (and not science!) can restore her ability to conceive. The implications of this barrenness should not be lost on us for the ties between notions of motherhood and American female identity undoubtedly remain even if they are not as firm as they might have been in earlier years. In a rather groan-worthy line, Cordelia explicitly describes her husband’s request to intervene as “playing God,” which of course directly mirrors the story of Frankenstein and his creation.

Returning to FrankenKyle for a moment, should we really be surprised that Zoe is at the center of all of this? As one whose name suggests that she is the embodiment of life and yet brings death (in the act of what brings about life!), she is precisely the one who would be involved in the reanimation of Kyle. Ignoring the seemingly unearned emotional connection for a moment, Zoe’s ability to wake a man with a kiss was an interesting reversal of the Snow White trope that has long been ingrained in our heads. And yet there is a curious way in which the power of witches continues to be tied to concepts of emotion and feeling, which have traditionally been the province of women. Furthermore, the kiss of life also opens up questions about Zoe’s abilities regarding her powers and the connection to Misty’s compulsion to arrive.

On another level I also struggle with Zoe’s decision (and this is related to my feeling that her emotional connection is unearned) as bringing Kyle back also seems to indicate that you are not only imposing your will upon nature but also upon Kyle. As acknowledged in the car ride home from the morgue, Kyle might not have wanted to come back, much less suffer the indignity of being a shadow of his former self. Moreover, if Kyle were to regain a measure of sentience (which Murphy’s interviews have suggested that this is not necessarily the case), he must also eventually grapple with the possibility of dying, which also seems like a horrible punishment to visit upon someone. And really, what kind of life is that?

Ultimately, in this episode we see many of the women clinging to life in various forms: Fiona continues her quest to achieve immortality, Laveau is shown to have been harboring her Minotaur lover, LaLaurie laments the life she once knew, Cordelia goes dark in order to foster her ability to bring forth life, and Zoe follows through on her desire to reconnect with the life of Kyle. As Tithonus learned, eternal life is not the same as eternal youth and the show seems to be conflating the two. (Which, to be fair, I would be totally fine with a potion or magic or science granting both but I would like it made clear that they are not necessarily the same thing.) The question that undergirds all of this, then, is about the value of life. What is a life worth, what does a life mean, and what does it mean to lose/give/take a life?

As a last aside, I also remain curious about is whether the universe of the show will ascribe to some sort of cosmic balance in that it trades a life taken for a life given. Nothing about the show thus far suggests that this will be the case but I think it is an interesting point to consider if we are thinking about how the forces of nature and magic intertwine with one another. If Misty is right that “Mother Nature has an answer for everything,” should we see attempts at circumventing nature as a short-term gain in exchange for an eventual comeuppance?

*Also what to make of the assertion that Queenie did exceedingly well in math but is working at a fried chicken restaurant and that Laveau (who is portrayed as the ultimate Voodoo Queen) is running a beauty parlor in the Ninth Ward? Normally I would be interested in thinking about how these scenarios provided a commentary on opportunity for black people in New Orleans and/or suggested something about reinvesting your skills into your community but I just don’t trust Ryan Murphy to be particularly insightful about race and class issues that are outside his norm.

Like So Much Processed Meat

“The hacker mystique posits power through anonymity. One does not log on to the system through authorized paths of entry; one sneaks in, dropping through trap doors in the security program, hiding one’s tracks, immune to the audit trails that we put there to make the perceiver part of the data perceived. It is a dream of recovering power and wholeness by seeing wonders and not by being seen.”

—Pam Rosenthal

Flesh Made Data: Part I

This quote, which comes from a chapter in Wendy Hui Kyong Chun’s Control and Freedom on the Orientalization of cyberspace, gestures toward the values embedded in the Internet as a construct. Reading this quote, I found myself wondering about the ways in which identity, users, and the Internet intersect in the present age. Although we certainly witness remnants of the hacker/cyberpunk ethic in movements like Anonymous, it would seem that many Americans exist in a curious tension that exists between the competing impulses for privacy and visibility.

Looking deeper, however, there seems to be an extension of cyberpunk’s ethic, rather than an outright refusal or reversal: if cyberpunk viewed the body as nothing more than a meat sac and something to be shed as one uploaded to the Net, the modern American seems, in some ways, hyper aware of the body’s ability to interface with the cloud in the pursuit of peak efficiency. Perhaps the product of a self-help culture that has incorporated the technology at hand, we are now able to track our calories, sleep patterns, medical records, and moods through wearable devices like Jawbone’s UP but all of this begs the question of whether we are controlling our data or our data is controlling us. Companies like Quantified Self promise to help consumers “know themselves through numbers,” but I am not entirely convinced. Aren’t we just learning to surveil ourselves without understanding the overarching values that guide/manage our gaze?

Returning back to Rosenthal’s quote, there is a rather interesting way in which the hacker ethic has become perverted (in my opinion) as the “dream of recovering power” is no longer about systemic change but self-transformation; one is no longer humbled by the possibilities of the Internet but instead strives to become a transformed wonder visible for all to see.

Flesh Made Data: Part II

A spin-off of, and prequel to, Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009), Caprica (2011-2012) transported viewers to a world filled with futuristic technology, arguably the most prevalent of which was the holoband. Operating on basic notions of virtual reality and presence, the holoband allowed users to, in Matrix parlance, “jack into” an alternate computer-generated space, fittingly labeled by users as “V world.”[1] But despite its prominent place in the vocabulary of the show, the program itself never seemed to be overly concerned with the gadget; instead of spending an inordinate amount of time explaining how the device worked, Caprica chose to explore the effect that it had on society.

Calling forth a tradition steeped in teenage hacker protagonists (or, at the very least, ones that belonged to the “younger” generation), our first exposure to V world—and to the series itself—comes in the form of an introduction to an underground space created by teenagers as an escape from the real world. Featuring graphic sex, violence, and murder, this iteration does not appear to align with traditional notions of a utopia but might represent the manifestation of Caprican teenagers’ desires for a world that is both something and somewhere else. And although immersive virtual environments are not necessarily a new feature in Science Fiction television, with references stretching from Star Trek’s holodeck to Virtuality, Caprica’s real contribution to the field was its choice to foreground the process of V world’s creation and the implications of this construct for the shows inhabitants.

Seen one way, the very foundation of virtual reality and software—programming—is itself the language and act of world creation, with code serving as architecture. If we accept Lawrence Lessig’s maxim that “code is law”, we begin to see that cyberspace, as a construct, is infinitely malleable and the question then becomes not one of “What can we do?” but “What should we do?” In other words, if given the basic tools, what kind of existence will we create and why?

Running with this theme, the show’s overarching plot concerns an attempt to achieve apotheosis through the uploading of physical bodies/selves into the virtual world. I found this series particularly interesting to dwell on because here again we had something that recalls the cyberpunk notion of transcendence through data but, at the same time, the show asked readers to consider why a virtual paradise was more desirous than one constructed in the real world. Put another way, the show forces the question, “To what extent do hacker ethics hold true in the physical world?”

[1] Although the show is generally quite smart about displaying the right kind of content for the medium of television (e.g., flushing out the world through channel surfing, which not only gives viewers glimpses of the world of Caprica but also reinforces the notion that Capricans experience their world through technology), the ability to visualize V world (and the transitions into it) are certainly an element unique to an audio-visual presentation. One of the strengths of the show, I think, is its ability to add layers of information through visuals that do not call attention to themselves. These details, which are not crucial to the story, flush out the world of Caprica in a way that a book could not, for while a book must generally mention items (or at least allude to them) in order to bring them into existence, the show does not have to ever name aspects of the world or actively acknowledge that they exist.

Until It’s Vegas Everywhere We Are

In 1954, psychologists James Olds and Peter Milner conducted a landmark experiment in the field of Behaviorism: implanting electrodes into rats, Olds and Milner allowed the animals to stimulate the pleasure centers of their brains via a lever. Depressing the control up to 700 times a day, the allure of the stimulation was so strong that, given a choice between pleasure and food, rats eventually died from exhaustion.

In 1954, psychologists James Olds and Peter Milner conducted a landmark experiment in the field of Behaviorism: implanting electrodes into rats, Olds and Milner allowed the animals to stimulate the pleasure centers of their brains via a lever. Depressing the control up to 700 times a day, the allure of the stimulation was so strong that, given a choice between pleasure and food, rats eventually died from exhaustion.

Initial reactions to this scenario often include a measure of shock and disbelief as individuals try to make sense of what they observe. Why would an animal literally pleasure itself to death? Although we as humans—and supposed exemplars of rationality—might make different choices in a similar situation, the lesson to learn from the Olds and Milner study is that the pursuit of pleasure can be a powerful influence on our lives.

The continued resonance of the Olds and Milner experiment is perhaps most evident in the appearance of “click bait.” Typically relying on provocative visual elements (e.g., a headline and/or image), the concept of click bait adopts strategies and logics gleaned from advertising as it employs old models that form a direct correlation between value and number of views. Inhabiting a space at the intersection of attention, pleasure, and economic forces, the concept of click bait represents an interesting object of inquiry as we read about notions of visibility.

The continued resonance of the Olds and Milner experiment is perhaps most evident in the appearance of “click bait.” Typically relying on provocative visual elements (e.g., a headline and/or image), the concept of click bait adopts strategies and logics gleaned from advertising as it employs old models that form a direct correlation between value and number of views. Inhabiting a space at the intersection of attention, pleasure, and economic forces, the concept of click bait represents an interesting object of inquiry as we read about notions of visibility.

Click bait does not invite us to linger, to savor, or to contemplate; click bait entreats us to look but not to see or to imagine, encapsulating Nicholas Mirzoeff’s understanding of visuality as a force that is determined to impose a singular unified vision of the world on multiple levels. Take online slideshows as an example of notorious forms of click bait that rob us of the ability to curate our own collections and to develop our own connections between things. Visual displays such as these provide tangible examples of Mirzoeff’s position that visuality operates through classifying, ordering, and naturalizing—an assertion that offers a certain amount of overlap with the role that language plays in our experiences as it mediates the transformation from sensation into perception. Here, the price that we pay for a brief moment of pleasure is the loss of our imagination—we not only dampen our ability to see other realities but fundamentally inhibit our ability to believe that they can even exist. Click bait represents an entity that screams for our attention, offering a fleeing moment of pleasure in exchange for the opportunity to subvert our vision to its purposes as it directs us where to look.

Wrestling with these very notions of sight and seeing, Kanye West’s music video for “All of the Lights” speaks to the way in which stimulation and novelty has become increasingly integrated into the everyday experience of urbanized individuals.

The first viewing of West’s video is often difficult as viewers are confronted with frenetic visuals that invoke the light-filled cityscapes of Tokyo, Times Square, and Las Vegas. And yet, what strikes me is just how readily one becomes attuned to a display that boasts a prominent seizure warning.[1] What does this suggest about the way in which we have been trained to respond to visual stimuli in general and to incessant calls for our attention in particular? Or, perhaps more frighteningly, just how quickly we can habituate ourselves into unseeing.

“All of the Lights” is an interesting cultural artifact for me because it also wrestles with these notions of seeing and being seen through the lyrics of the song itself: concerned with the attempts of a parolee to see his daughter (and for his daughter to see him), the song (unwittingly) builds upon Mirzoeff’s position on the relatedness between autonomy and sight.[2] And yet the song goes further as it calls attention to situations that cultural outsiders might willfully refrain from seeing. “Turn up the lights in here, baby / Extra bright, I want y’all to see this,” the song implores as it endeavors to realize Mirzoeff’s suggestion that visuality be countered through the presentation of alternate forms of realism. Additionally, the sequence pays homage to the opening credits for Gaspar Noe’s Enter the Void, a movie that plays with perspective and perception, continually reminding us to pay attention to the fact that we are paying attention.[3]

This sort of critical self-reflection is, as Cathy Davidson notes in her book Now You See It, a helpful reminder that we have been trained to pay attention to particular facets of the world—mistakenly inferring that these elements constitute the world in its entirety—at the expense of others. Davidson points to the structural and systematic ways in which we are socialized to pay attention to, and thus value, particular objects, ideas, and actions over others. From family, to school, to politics, institutions shape what is worthy of attention and therefore what are values are; attention, then, is not just about what we see but also how we see it.

Chris Tokuhama

[1] Although difficult to watch in its entirety, Enter the Void’s title sequence is particularly memorable for the way in which it disrupts the viewing process and dislocates the viewer as foreshadowing for the experience that follows.

[2] On page 25 of The Right to Look Mizroeff writes, “By the same token, the right to look is never individual: my right to look depends on your recognition of me, and vice versa.”

[3] Similarly, I think that the opening scenes of American Horror Story: Asylum (https://www.facebook.com/americanhorrorstory/app_216209925175894) perform a similar function, which ties into the season’s overall theme of truth/reality. The thing that the show makes evident is the way in which our interaction with the world is intimately tied to our perception of it.

Communicating Interest and the Interest of Communication

In “That’s Interesting! Towards a Phenomenology of Sociology and a Sociology of Phenomenology” Murray Davis outlines a number of variations on a single theme: the reversal of established expectations constitutes the basis for an “interesting” finding. Although Davis adequately details of why a particular publication or study may hold interest for an audience, we must be careful not to equate interest with value (or, as Davis notes, with accuracy).

Additionally, we might note how Davis’ construction of binaries may struggle to find resonance is a post-modern world. While the core of Davis’ argument may continue to hold true, the language may benefit from a slight alteration: instead of “X” versus “non-X” we may consider how interesting studies may contrast “always X” and “not always X.” For example, we might point to interesting developments in audience studies that argue against the passive nature of consumers. Although we see the emergence of agency and active audience, this phenomenon exists alongside passive viewing suggesting that our dominant assumptions about the audience need to be refined but also that an either/or binary must give way to a model that incorporates a both/and stance.

However, regardless of minor issues, we can apply Davis’ notion to a host of current theories in order to assess the relative level of interest that they may hold. Media theories, for example, may be considered “interesting” as they often unpack and denaturalize adopted or learned practices. The great potential for theories of mass media or media and culture to be considered “interesting” lies in their ability to challenge the simplicity of the everyday (e.g., watching television, reading a newspaper, or browsing the Internet), arguing that media is both impacted and consumed in incredibly complex ecologies. For example, we readily see that theory like that of the knowledge gap lends itself to the conclusion that the same media artifact can hold vastly different amounts of information for various populations (with extensions of this to media literacy) and, from there, it is a short leap to the notion that various groups may respond to, or be affected by, media in different manners.

The realm of media also invokes questions about the ways in which communication is affected by information and communication technology. Ranging from issues of presence to uses and gratifications and computer mediated communication, this cluster of theories attempts to investigate the ways in which communication aided by technology may in fact be a more complex process than originally thought. Put another way, these theories question the assumptions made around the design and use of communication technologies challenging the notion that the protocols surrounding technology adoption and implementation are in any way natural.

Similar to media, of which the average person typically has an intuitive or common sense understanding, we can consider how theories of persuasion and advertising may be deemed “interesting” as they cause us to reconsider something that we rarely contemplate because it is ever-present and, on some level, simply assumed to be part of life. Alternatively, we see that persuasion theory can also be interesting as it deflates the sensationalism of catch phrases like “subliminal advertising” and explores how the process of priming actually works. This field has also seen a minor resurgence after the popularity of Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink with regard to the process of decision making for we have been exposed to the idea that our choices may not be entirely up to us (and who doesn’t love a good conspiracy theory?).

Ultimately, although we see that Davis provides one method for determining whether a project is “interesting,” we must also remember that not everything that is of interest is also significant. Using novelty as a guide may give us a place to start our investigation but we must also think carefully about the import of the cultural assumptions that surround our questions. As scholars, we must also challenge ourselves and our work to go beyond a threshold of “interesting” and be relevant and meaningful.

Secrets and Li(v)es

In retrospect, it was rather obvious: I was intrigued by Cultural Studies before I even knew what it was. My fascination with PostSecret—a site that began as a public art project wherein people anonymously mailed in secrets on postcards—began in early 2005, particularly timely given that I was just about to graduate from college and was feeling no small amount of anxiety about what would become of my life. Beyond an emotional connection, however, I also loved looking at the way in which the simple declarative statements combined with typography and associated images to produce a rather powerful artifact; the choices that people made in displaying their secrets—these innermost thoughts—fascinated me and I started down my path toward becoming a sort of amateur semiotician.

Over the years, the site has floated around in my head but one of the foundations of the project/website also serves as one of its greatest barriers to study: the anonymous submission process. All postcards are sent to an intermediary, Frank Warren, who selects and uploads the images to the site—this means that the original authors are impossible to study without violating users’ trust (and possibly a few laws). As a result, I cannot ascertain who feels compelled to create a postcard and, at times, that failure troubles me for these are the people who most need support.

I don’t mean to imply that I wish to know exactly who wrote which card but I would love to get an analysis of the demographics for the makers. What types of people feel the need to create cards and send them in? Are these individuals who feel as though they cannot express their voice through other channels? How does the population of makers compare to the population of readers? One might argue that there is likely to be a certain amount of overlap but the very notion that one set is driven to craft something is intriguing to me. And even if we were able to recruit study participants (ignoring likely IRB complications for a moment), we would have to suspect a kind of volunteer bias, particularly given the nature of the material being disclosed on the site.

So instead I endeavor to study the way in which the site and its associated products (museum exhibits, books, and speaking engagements) intersect with, and create, culture. The project raises a number of questions for me, specifically how it reflects our current culture of confession. In particular, I often wonder how the current state of media might have affected the success of a movement like PostSecret.

So instead I endeavor to study the way in which the site and its associated products (museum exhibits, books, and speaking engagements) intersect with, and create, culture. The project raises a number of questions for me, specifically how it reflects our current culture of confession. In particular, I often wonder how the current state of media might have affected the success of a movement like PostSecret.

Growing up, I remember watching the first seasons of The Real World and Road Rules on MTV and was always entranced by the confessional monologues. As a teen, the confessionals possessed a conspiratorial allure, for I was now privy to insider information about the inner workings of the group. However, looking back, I wonder if this constant exposure to the format of the confessional has changed the way that I think about my secrets.

The confessional has become rather commonplace on the slew of reality shows that have filled the airwaves of the past decade and the practice creates, for me, an interesting metaphor for how Americans have to come to deal with our struggles. As confessors sit in an isolation booth, they simultaneously talk to nobody and to everybody; place this in stark contrast to the typical connotation of “confession” and its associated images of an intimate discussion with a priest.

PostSecret, in some ways, is merely a more vivid take on St. Augustine’s seemingly far-removed literary testimony in Confessions and yet also an extension of the modern practice of mediated confession: we hold our secrets in until we get the chance to broadcast them across media channels. We exist in a culture that has transformed the act of confession into a spectacle—we celebrate press conference apologies and revelations of sexual orientation make the front page. Has our desire for information transformed us into a society that hounds after secrets, compelling others to confess the things they hope to keep to themselves? Are secrets worth something only in their threat to expose or reveal? What does this whole practice of secret keeping tell us about the way that we relate to ourselves and to others? We oscillate between silence and shouting—perhaps we’ve forgotten how to talk—and we are desperate to make connections, to find validation, and to be heard. Are we so consumed with tending to our own secrets and revealing those of others that we have, in some ways, become nothing more than a site of secrets? How does this intersect with notions of empathy and narcissism?

PostSecret, in some ways, is merely a more vivid take on St. Augustine’s seemingly far-removed literary testimony in Confessions and yet also an extension of the modern practice of mediated confession: we hold our secrets in until we get the chance to broadcast them across media channels. We exist in a culture that has transformed the act of confession into a spectacle—we celebrate press conference apologies and revelations of sexual orientation make the front page. Has our desire for information transformed us into a society that hounds after secrets, compelling others to confess the things they hope to keep to themselves? Are secrets worth something only in their threat to expose or reveal? What does this whole practice of secret keeping tell us about the way that we relate to ourselves and to others? We oscillate between silence and shouting—perhaps we’ve forgotten how to talk—and we are desperate to make connections, to find validation, and to be heard. Are we so consumed with tending to our own secrets and revealing those of others that we have, in some ways, become nothing more than a site of secrets? How does this intersect with notions of empathy and narcissism?

These questions are, of course, not unique to PostSecret but I think that the project does offer a slightly different entry point into a community that can be secretive. Moreover, the development of an iPhone app might cause us to reflect on what is represented by the barrier of physically making and sending a postcard—does convenience lower the barrier to what might be considered a “secret”? As of yet, there does not seem to be a noticeable difference between the secrets sent in through the postal mail and those generated by the app but this might be due to the fact that secrets are screened and selected prior to their public display.

On a Mission?

Consumables are the product of how a culture understands its relationship to the world around it (although it should be noted that they are not the only way) with items following an underlying logic about the way in which the world works and often fulfilling a perceived need for consumers. Manufactured products, then, are not just products but also serve as tangible artifacts of entire ideological structures: “products” are the result of, and indicative of, a specific type of relationship between consumer and consumable and it is this relationship that speaks to the underlying ideology. Accordantly, it does not seem out of the question to argue that the trade of products also allows for the transmission of values.

Consumables are the product of how a culture understands its relationship to the world around it (although it should be noted that they are not the only way) with items following an underlying logic about the way in which the world works and often fulfilling a perceived need for consumers. Manufactured products, then, are not just products but also serve as tangible artifacts of entire ideological structures: “products” are the result of, and indicative of, a specific type of relationship between consumer and consumable and it is this relationship that speaks to the underlying ideology. Accordantly, it does not seem out of the question to argue that the trade of products also allows for the transmission of values.

Although this process is most likely apparent when trading groups are most dissimilar (e.g., when trade is first established between two communities), we can continue to glimpse aspects of this process occurring in our highly globalized Western societies. On one level, we have products that are closely connected to our understanding of culture that make their values highly visible—fashion, for example, transmits ideas through aesthetic (e.g., color, structure, cut, textile choice, etc.) that reflect how a particular group of people see themselves. Beyond just notions of status or ornamentation, we might also consider how a group’s use of materials like fur or toxic dye also reveal how a culture positions itself relative to other things in the world: things in the environment are tools or resources to be used in service of humans.

Certainly, cultural products like fashion, film/television, art, music, comics, and literature all contain a fairly visible sensibility that is easier to recognize (if not isolate) and discuss. Take, for example, the highly visible way in which Disneyland/Disneyworld portray a very particular understanding of the world through the ride “It’s a Small World.” Getting past anger that may arise from stereotypes or characterizations, we see that the animatronic dolls depict the world through a set of Western eyes (which, given their locations and likely audience makes a certain amount of sense). But also fascinating is the way in which this ride is reproduced around the world and how those iterations help to reveal the ways in which a product can not only reflect, but produce, ways in which we see ourselves in our surroundings.

Here we can look at how a likely Western family is experiencing China’s take on Disney’s version of countries like China—incredibly rich, to say the least. But we can also think about how theme parks like Disneyland/Disneyworld represent a physical sort of colonization in countries like Japan and France. Colonization, it seems, has become less about invasion and domination through force and more concerned with buying into a particular ideology through consumption; put another way, our missionaries are no longer people but products.

But we can also consider how the development of the Internet has allowed for an incredible flow of information around the world. While there are certainly positive aspects to this development (e.g., the potential for access to information and the creation of different channels for individuals to be heard), we must also grasp with the very real concerns that a free flow of information also creates a competition for survival amongst the ideas of the world. In an ideal world, this sort of competition would be the “survival of the best,” but increasingly it seems as though it is the “survival of the loudest.”

As we discussed last week, English has an incredible influence on the types of articles and information that are published in scientific journals (the influence is less in journals that concern Natural Science but English seems to continue to exert a large presence). Although some of my classmates may be able to speak to this in more nuanced ways, I also wonder about the effect that the dominance of English has on the ways in which we understand the world. I am not fluent in another language but find that when I try to speak in Japanese, I need to think in Japanese and that this causes me to adapt a different set of behaviors and thoughts. If this sort of shift occurs on a larger scale, we then not only have to question the content of the information being circulated around the world but also the form in which it manifests.

As we discussed last week, English has an incredible influence on the types of articles and information that are published in scientific journals (the influence is less in journals that concern Natural Science but English seems to continue to exert a large presence). Although some of my classmates may be able to speak to this in more nuanced ways, I also wonder about the effect that the dominance of English has on the ways in which we understand the world. I am not fluent in another language but find that when I try to speak in Japanese, I need to think in Japanese and that this causes me to adapt a different set of behaviors and thoughts. If this sort of shift occurs on a larger scale, we then not only have to question the content of the information being circulated around the world but also the form in which it manifests.

The Brass Age (Redux?)

What else is speculative fiction other than a bagful of nickels?

This image, from Dexter Palmer’s book, has long haunted me since I first encountered it. Hope, possibility, dreams unrealized—the nickels manifest an interesting relationship between Harold and technology that extended far beyond the original creator’s intention. And, in a way, isn’t this what steampunk and science fiction are all about? It is what is represented by the nickels rather than the nickels themselves that are important and we might even turn to Saussure’s semiotic labels of objects, signified, sign as we realize that there also exists a tension because the only way to manifest the dreams is to spend the nickel—what is the balance between dreams realized and the pull of dreams left to dream?

This image, from Dexter Palmer’s book, has long haunted me since I first encountered it. Hope, possibility, dreams unrealized—the nickels manifest an interesting relationship between Harold and technology that extended far beyond the original creator’s intention. And, in a way, isn’t this what steampunk and science fiction are all about? It is what is represented by the nickels rather than the nickels themselves that are important and we might even turn to Saussure’s semiotic labels of objects, signified, sign as we realize that there also exists a tension because the only way to manifest the dreams is to spend the nickel—what is the balance between dreams realized and the pull of dreams left to dream?

Ultimately, however, we must also ask ourselves just how “punk” is steampunk? If the term endeavors to draw upon the Western history of punks from the 1970s, it must then speak to a form of subversion or resistance against the dominant culture of the time. Although one might argue that the aesthetic of steampunk along with an emphasis on construction or reappropriation of machines certainly represents a challenge to the status quo, the centrality of technology in the lives of steampunks certainly seems to remain aligned with current views. Technology looks different, but does it function in a fundamentally different way?

Although a casual fan of the culture, I also continue to wonder about just how deep this love of Victorian-era ideals go. Perhaps I am just sensitized to the resurgence of Gothic (e.g., horror, gothic Lolita, etc.) and Victorian because of my research interests? I find myself struggling with the grand visions put forth in steampunk (not unlike other forms of technological utopia we have encountered previously in the course) as erasing the very real struggles that surrounded the appearance of steam-powered technology in the 19th century. In addition to the pollution and physical hazards mentioned in Rebecca Onion’s piece, I also think about how the new machine culture affected workers’ health. But even beyond the scope of the machine and the factory, steampunk seems to pluck out fetishized elements of clockwork while leaving the very real (at the time) menaces of disease, improper sanitation, and corpse stealing that were intertwined with developing technology in the Victorian age.

But then again, perhaps I am reading this all wrong. Does steampunk speak to a deep cultural need for us to strip away the layers of shine and sheen that surround modern implementations of technology? To see the gears and pistons is to see behind the curtain and experience a different type of technological wonder all together. Is there a sort of excitement that comes from knowing that gadgets might not work? And, as mentioned earlier, surely the culture of production that pervades the experience of being steampunk speaks to an increasingly diminished notion of the average person as tinkerer.

But then again, perhaps I am reading this all wrong. Does steampunk speak to a deep cultural need for us to strip away the layers of shine and sheen that surround modern implementations of technology? To see the gears and pistons is to see behind the curtain and experience a different type of technological wonder all together. Is there a sort of excitement that comes from knowing that gadgets might not work? And, as mentioned earlier, surely the culture of production that pervades the experience of being steampunk speaks to an increasingly diminished notion of the average person as tinkerer.

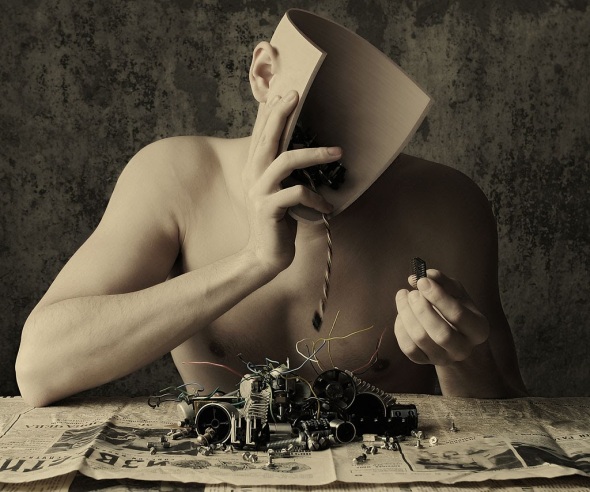

Body Assembly

There is, for Western male bodies in particular, a very distinct sense of the body as discrete and whole. In contrast to permeable female body—associated with tears, lactation, childbirth, and menstruation, women demonstrate a tendency to ooze—male bodies appear much more concerned with integrity and resistance to invasion or penetration.

The male anxieties surrounding penetration are also a bit ironic given that, in some ways, the current ideals of straight Western male bodies derive from an attempt by the gay community to respond to the threat of AIDS. In short, one factor in the rise of the ideal hard body—although certainly not the only influence—was the effort made by gay individuals to project a healthy and robust body in the 1980s. As AIDS was considered a “wasting disease” at the time, exaggerated musculature served as an immediate visual signal that one did not have the disease. As this particular image propagated in society, societal norms surrounding the male body changed and straight men began to adopt the new form, although importantly not for the same reasons of gay men.

The male anxieties surrounding penetration are also a bit ironic given that, in some ways, the current ideals of straight Western male bodies derive from an attempt by the gay community to respond to the threat of AIDS. In short, one factor in the rise of the ideal hard body—although certainly not the only influence—was the effort made by gay individuals to project a healthy and robust body in the 1980s. As AIDS was considered a “wasting disease” at the time, exaggerated musculature served as an immediate visual signal that one did not have the disease. As this particular image propagated in society, societal norms surrounding the male body changed and straight men began to adopt the new form, although importantly not for the same reasons of gay men.

This process, then, challenges the naturalization of the ideal body—and even the idea of the body itself. The concept of the body can be seen as a constant site of negotiated meaning as our understanding of what the body is (and is not) arises out of an intersection of values; this means that we must look closely at the ways in which we privilege one form of the body over another, maintaining a static arbitrary form in the process.

Here, Jussi Parikka’s notion of body as assemblage offers an interesting lens through which to examine the concept of the body: the “body,” in a sense is not only an amalgamation of parts, sensations, memories, and events but also is forged in the interaction between the components that make up the body and those that surround it. What if we were to rethink the sacred nature of the body and instead understand it as a fusing of parts on multiple levels? Would we care as much about the ways in which organic and inorganic pieces interacted with our bodies? What if we changed our understanding of our body as inherently natural and saw it as a prosthetic? The state of the body is in constant flux as it responds to and affects the world around it—put another way, the body is engaged in a constant dialogue with its surroundings.

Here, Jussi Parikka’s notion of body as assemblage offers an interesting lens through which to examine the concept of the body: the “body,” in a sense is not only an amalgamation of parts, sensations, memories, and events but also is forged in the interaction between the components that make up the body and those that surround it. What if we were to rethink the sacred nature of the body and instead understand it as a fusing of parts on multiple levels? Would we care as much about the ways in which organic and inorganic pieces interacted with our bodies? What if we changed our understanding of our body as inherently natural and saw it as a prosthetic? The state of the body is in constant flux as it responds to and affects the world around it—put another way, the body is engaged in a constant dialogue with its surroundings.

On a macro scale, this adaptation might take the form of Darwinian evolution but on an individual level, we might also think about things like scars or antibodies as ways in which our body (and not our mind!) evidences a form of memory as it has been impacted by the world around it. Although layers of meaning are likely imposed upon these bodily artifacts, on their most basic level they serve as reminders that, as stable as they seem, our bodies continually contain the potential to change.

And, ultimately, it is this potential for transcendence that forms a thread through most of my work. Stretching across the lineage of Final Girls who had power in them all along, to youth striving to maximize their education, to the transhumanist tendency to push the boundaries of the body, I hold most affinity for people who cry, “This is not all that I am.”

Eat My Dust: Uncovering who is left behind in the forward thinking of Transhumanism

It should come as no surprise that the futurist perspective of transhumanism is closely linked with Science Fiction given that both areas tend to, in various ways, focus on the intersection of technology and society. Generally concerned with the ways in which technology will serve to enhance human beings (along the way possibly evolving past “human” to become “posthuman”), the transhumanist movement generally adopts a positivist stance as it envisions a future in which disease and aging are eradicated or cognitive processes accelerated. [1] In one way, transhumanism is presented as a cure-all for the problems that have plagued human beings throughout our history, providing hope that our fragile, corruptible, mortal, and impermeable bodies can forever be augmented, maintained, fixed, or reconstituted. A seductive promise, surely. Science Fiction then takes the ideas presented by transhumanist theory and makes them a little more tangible, affording us the opportunity to visit these futurist communities as we dream about how our destiny will be changed for the better while also allowing us to glimpse warnings against hubris through works like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Without giving it much thought, it seems as though we are readily able to spot the presence of transhumanism in Science Fiction—but what if we were to reverse the gaze and instead use Science Fiction as a critical lens through which transhumanism could be viewed and understood? In short, what are lessons that we can garner from a close reading of Science Fiction texts can be used as tools to think through both the potential benefits and drawbacks of this particular direction for humanity?

Although admittedly an oversimplification, the utopia/dystopia binary gives us a place to start. Lest we become overly enamored with the potential and the promise of a movement like transhumanism, we must remember to ask ourselves, “Just whose utopia is it?”[2] Using Science Fiction as framework to understand the transhumanist movement, we are wary of a body of work that has traditionally excluded minority perspectives (e.g., the female gender or race) until called to explicitly express such views (see the presence of, and need for, works labeled as “feminist Science Fiction”). This is, of course, not to suggest that exceptions to this statement do not exist. However, it seems prudent here to mention that although the current landscape of Science Fiction has been affected by the democratizing power of the Internet, its genesis was largely influenced by an author-audience relationship that drew on experiences and knowledge primarily codified in White middle-class males. Although we can readily derive examples of active exclusion on the part of the genre’s actors (i.e., we must remember that this is not a property of the genre itself), we must also recognize a cultural context that steered various types of minorities away from fiction grounded in science and technology; for individuals who did not grow up idolizing the lone boy inventor/tinkerer or fantasizing about the space race, Science Fiction of the early- to mid-20th century did not readily represent reality of any sort, alternate, speculative, future, or otherwise.

If we accept that many of the same cultural factors that worked against diversity in early forms of Science Fiction continue to persist today with respect to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (Johnson, 1987; Catsambis, 1995; Nosek, et al., 2009) we must also question the vision put forth by transhumanists and be willing to accept that, for all its glory, the movement may very well represent an incomplete ideal state—invariably all utopias need revision. Although we might consider our modern selves as more progressive than authors of early Science Fiction, examination of current discourse surrounding transhumanism reveals a continued failure to incorporate discussions surrounding race (Ikemoto, 2005). In particular, this practice is potentially problematic as the Biomedical/Health field (in which transhumanism is firmly situated) has a demonstrated history of legitimizing multiple types of discrimination based on dimensions that include, but certainly are not limited to, race and gender. By not attempting to understand the implications of the movement from the viewpoint of multiple stakeholders, transhumanism potentially becomes a site for dominant ideology to reinforce its sociocultural constructions of the biological body. Moreover, if we have learned anything from the ways in which new media use intersects with race and socioeconomic status, we must be wary of the ways in which technology/media can exacerbate existing inequalities (or create new ones!). The issue of accesses to the technology of transhumanism immediately becomes pertinent as we see the potential for the restratification of society according to who can afford (broadly defined, including not just to cost but also including things like missed work due to recovery time) to have these procedures performed. In short, much like in Science Fiction, we must not only question who the vision is authored by, but also who it is intended for. Yet, far from suggesting that current transhumanist aspirations are necessarily or inherently incompatible with other strains, I merely argue that many types of voices must be included in the conversation if we are to have any hope of maintaining a sense of human dignity.

If we accept that many of the same cultural factors that worked against diversity in early forms of Science Fiction continue to persist today with respect to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (Johnson, 1987; Catsambis, 1995; Nosek, et al., 2009) we must also question the vision put forth by transhumanists and be willing to accept that, for all its glory, the movement may very well represent an incomplete ideal state—invariably all utopias need revision. Although we might consider our modern selves as more progressive than authors of early Science Fiction, examination of current discourse surrounding transhumanism reveals a continued failure to incorporate discussions surrounding race (Ikemoto, 2005). In particular, this practice is potentially problematic as the Biomedical/Health field (in which transhumanism is firmly situated) has a demonstrated history of legitimizing multiple types of discrimination based on dimensions that include, but certainly are not limited to, race and gender. By not attempting to understand the implications of the movement from the viewpoint of multiple stakeholders, transhumanism potentially becomes a site for dominant ideology to reinforce its sociocultural constructions of the biological body. Moreover, if we have learned anything from the ways in which new media use intersects with race and socioeconomic status, we must be wary of the ways in which technology/media can exacerbate existing inequalities (or create new ones!). The issue of accesses to the technology of transhumanism immediately becomes pertinent as we see the potential for the restratification of society according to who can afford (broadly defined, including not just to cost but also including things like missed work due to recovery time) to have these procedures performed. In short, much like in Science Fiction, we must not only question who the vision is authored by, but also who it is intended for. Yet, far from suggesting that current transhumanist aspirations are necessarily or inherently incompatible with other strains, I merely argue that many types of voices must be included in the conversation if we are to have any hope of maintaining a sense of human dignity.

And dignity[3] plays an incredibly important role in bioethical discussions as we being to take a larger view of transhumanism’s potential effect, folding issues of disability into the discussion as we contemplate another (perhaps more salient) way in which society can act to inscribe form onto a body. Additionally, mention of disability forces an expansion in the definition of transhumanism beyond mere “enhancement,” with its connotation of augmentation of able-bodied individuals, to include notions of treatment. Although beyond the scope of this paper, the treatment/enhancement distinction is worth investigating as it not only has the potential to designate and define concepts of normal functioning (Daniels, 2000) but also suffers from a general lack of consensus regarding use of the terms “treatment” and “enhancement” (Menuz, Hurlimann, & Godard, 2011). But, looking at the overlap of treatment, enhancement, and disability, we must ask ourselves questions like, “If one of the potential benefits of transhumanism is the prevention and/or rectification of conditions like disability and deformity, who should be fixed? Who deserves to be fixed? But, most importantly, who needs to be fixed?”

Continuing to apply perspectives used to analyze the intersection of race, class, and technology, we see the potential for transhumanism thought to impose a particular kind of label onto individual bodies, inscribing a particular system of values in the process. Take, for example, Sharon Duchesneau and Candy McCullough who have been criticized for actively attempting to conceive a deaf child (Spriggs, 2002). Although the couple (both of whom are deaf) do not consider deafness to be a disability or a liability, a prevailing view in America works to force a particular type of identity onto the couple and their child (i.e., deafness is abnormal) and the family will undoubtedly be forced to eventually confront thinking informed by transhumanism in justifying their choice and very existence.

However, even seemingly straightforward cases like Olympic hopeful Oscar Pistorius have forced us to grapple with new questions regarding the consideration of recipients of biomedical augmentation. Born without fibula, a state that would likely be classified as “disabled” by himself and others, Oscar Pistorius won gold medals in the 100, 200, and 400 meter events at the 2008 Paraolympic Games but was initially banned from entering the Olympic Games due to concern that his artificial legs conferred an unfair advantage. Although this ruling was later overturned, Pistorius failed to make the qualifying time to participate in the 2008 Olympics Games. Pistorius has, however, met the qualifying standard for the 2012 Games and his participation will assuredly affect future policy regarding the use of artificial limbs as well as a renegotiation of the term “disabled” (Burkett, McNamee, & Potthast, 2011; Van Hilvoorde & Landeweerd, 2010). Interestingly, Pistorius also raises larger issues about the nature of augmentation in Sport, an area that has long wrestled with the concept of competitive advantages conferred through body modification and enhancement.

However, even seemingly straightforward cases like Olympic hopeful Oscar Pistorius have forced us to grapple with new questions regarding the consideration of recipients of biomedical augmentation. Born without fibula, a state that would likely be classified as “disabled” by himself and others, Oscar Pistorius won gold medals in the 100, 200, and 400 meter events at the 2008 Paraolympic Games but was initially banned from entering the Olympic Games due to concern that his artificial legs conferred an unfair advantage. Although this ruling was later overturned, Pistorius failed to make the qualifying time to participate in the 2008 Olympics Games. Pistorius has, however, met the qualifying standard for the 2012 Games and his participation will assuredly affect future policy regarding the use of artificial limbs as well as a renegotiation of the term “disabled” (Burkett, McNamee, & Potthast, 2011; Van Hilvoorde & Landeweerd, 2010). Interestingly, Pistorius also raises larger issues about the nature of augmentation in Sport, an area that has long wrestled with the concept of competitive advantages conferred through body modification and enhancement.

Ultimately we see that while improvements in human-computer interfaces, computer-mediated communication, neuroscience, and biomechanics paint a resplendent future full of possibilities for a movement like transhumanism, the philosophy also reveals a struggle over phrases like “human enhancement” that have yet to be resolved. Although I am personally most interested in issues of identity and religion that will most likely arise as a result of this cultural transformation (see Spezio, 2005), I want to suggest that larger societal issues must also be raised and discussed. Although we might understand the fundamental issue of transhumanism as a question of whether we should accept the body the way it is, I think the more instructive line of inquiry (if perhaps harder to initially understand) thoroughly examines the ways in which transhumanism builds upon a historical construction of the concept of the body as natural while simultaneously challenging it. Without such critical reflection, transhumanism, like many utopic endeavors, runs the risk of limiting our future to one that is restricted by the types of issues that we can imagine in the present; although our path forward is necessarily guided by the questions that we ask today, utopia turns to dystopia when we fixate on a idealized state and forget why we even bothered to seek advancement in the first place. If, however, we apply the theoretical frameworks provided by Science Fiction to our real lives and reconceptualize utopia as a process—a pursuit that is ongoing, reflexive, and dynamic—instead of as a product, we stand a chance of accomplishing what we sought to do without diminishing individual autonomy or being consumed by the very technology we hoped to integrate.

[1] Interestingly, in some conceptualizations, aging is now being understood as a disease-like process rather than a biological inevitability. Aside from the radical shift in thinking represented by a movement away from death as biological fact, I am fascinated by the ways in which this indicates a changing understanding of the “natural” state of our bodies.

[2] This should not suggest that a utopia/dystopia binary is the only way of considering this issue, but merely one way of utilizing language central to Science Fiction in order to understand transhumanism. Moreover, like most things, transhumanism is multidimensional and I am hesitant to cast it onto a good/bad dichotomy but I think that the notion of critical utopia can be instructive here.

[3] A complex notion itself worthy of detailed discussion. A recent issue of The American Journal of Bioethics featured a number of articles on the concept of dignity and how transhumanism worked to uphold or undermine it. See de Melo-Martin, 2010; Bostram, 2008; Sadler, 2010; Jotterand, 2010. Although “dignity” seems difficult to define concretely, Menuz, Hurlimann, and Godard suggest a “personal optimum state” based on cultural, socio-historical, biological, and psychological features (2011). One might note, however, that the highly indivdualized nature of Menuz, Hurlimann, and Godard’s criteria makes implimentation of policy difficult.

Works Cited

Bostram, N. (2008). Dignity and Enhancement. In A. Schulman (Ed.), Human Dignity and Bioethics: Essays Commissioned by the President’s Council on Bioethics (pp. 173-207). Washington, DC: The President’s Council on Bioethics.

Burkett, B., McNamee, M., & Potthast, W. (2011). Shifting Boundaries in Sports Technology and Disability: Equal Rights or Unfair Advantage in the Case of Oscar Pistorius? Disability and Society, 26(5), 643-654.

Catsambis, S. (1995). Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Science Education in the Middle Grades. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 32(3), 243-257.

Daniels, N. (2000). Normal Functioning and the Treatment-Enhancement Distinction. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 9, 309-322.

de Melo-Martin, I. (2010). Human Dignity, Transhuman Dignity, and All That Jazz. The American Journal of Bioethics, 10(7), 53-55.

Ikemoto, L. (2005). Race to Health: Racialized Discourses in a Transhuman World. DePaul Journal of Health Care Law, 9(2), 1101-1130.

Johnson, S. (1987). Gender Differences in Science: Parallels in Interest, Experience and Performance. International Journal of Science Education, 9(4), 467-481.

Jotterand, F. (2010). Human Dignity and Transhumanism: Do Anthro-Technological Devices Have Moral Status? The American Journal of Bioethics, 10(7), 45-52.

Menuz, V., Hurlimann, T., & Godard, B. (2011). Is Human Enhancement Also a Personal Matter? Science and Engineering Ethics.

Nosek, B. A., Smyth, F. L., Sriram, N., Lindner, N. M., Devos, T., Ayala, A., et al. (2009, June 30). National Differences in Gender: Science Stereotypes Predict National Sex Differences in Science and Math Achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(26), 10593–10597.

Sadler, J. Z. (2010). Dignity, Arete, and Hubris in the Transhumanist Debate. American Journal of Bioethics, 10(7), 67-68.

Spezio, M. L. (2005). Brain and Machine: Minding the Transhuman Future. Dialog: A Journal of Theology, 44(4), 375-380.

Spriggs, M. (2002). Lesbian Couple Create a Child Who Is Deaf Like Them. Journal of Medical Ethics, 283.

Van Hilvoorde, I., & Landeweerd, L. (2010). Enhancing Disabilities: Transhumanism under the Veil of Inclusion? Disability and Rehabilitation, 32(26), 2222-2227.

I Want to Break Free

It seems only fitting that Queen’s “I Want to Break Free” begins with a domestic scene that features a housewife vacuuming, for perhaps no time in recent history has been as evocative as the mid-20th century matriarch.[1] Arguably trading potential for security, women were indeed presented with “overchoice” as hundreds of new products became available for consumers—but although the sheer number of choices available increased, one might also argue that the meaningful choices that a woman could make also decreased as society restructured itself in the years following World War II. Science fiction offerings by authors like Pamela Zoline and James Tiptree, Jr. point to various roles for women in America at the time, illuminating the narrow ways in which women could insert themselves into a world that was not their own. Moreover, the path highlighted society lay fraught with ennui, boredom, monotony, and despair—so much so, in fact, that Pamela Zoline’s Sarah Boyle attempts to disrupt her routine and, in so doing, bring about the heat death of the universe (and the end of her suffering).

It seems only fitting that Queen’s “I Want to Break Free” begins with a domestic scene that features a housewife vacuuming, for perhaps no time in recent history has been as evocative as the mid-20th century matriarch.[1] Arguably trading potential for security, women were indeed presented with “overchoice” as hundreds of new products became available for consumers—but although the sheer number of choices available increased, one might also argue that the meaningful choices that a woman could make also decreased as society restructured itself in the years following World War II. Science fiction offerings by authors like Pamela Zoline and James Tiptree, Jr. point to various roles for women in America at the time, illuminating the narrow ways in which women could insert themselves into a world that was not their own. Moreover, the path highlighted society lay fraught with ennui, boredom, monotony, and despair—so much so, in fact, that Pamela Zoline’s Sarah Boyle attempts to disrupt her routine and, in so doing, bring about the heat death of the universe (and the end of her suffering).

Fast forward fifty years and we again see another batch of Desperate Housewives, who suffer from some of the same emotions as their 50s counterparts. Restless and losing a sense of self, the women on Marc Cherry’s drama attempt to illustrate that even well-to-do mothers living in gated communities still struggle to have it all.

And, in many ways, Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror have dealt with the same issues throughout the years, with witches in the 60s like Samantha Stevens (Bewitched) going through the same sorts of domestic trials as the modern Halliwell sisters (Charmed). Important in both of these shows is the presence of the accepting/tolerant (White) male who, although occasionally lacking in comprehension of women or their magic, is certainly understanding. In the case of Bewitched, we see a male who puts up with his wife’s misdeeds and tolerates the existence of magic even as he discourages its use.

Additionally, we see women in these shows often struggling with the expectations of motherhood, which raises notions about feminine identity, female bodies, and reproduction. Explored by Octavia Butler, we are introduced to the theme of male pregnancy, which often results in disastrous consequences for men.[2] Men’s bodies, it seems, cannot handle the task of birth as they are often destroyed in the process of labor.

Additionally, we see women in these shows often struggling with the expectations of motherhood, which raises notions about feminine identity, female bodies, and reproduction. Explored by Octavia Butler, we are introduced to the theme of male pregnancy, which often results in disastrous consequences for men.[2] Men’s bodies, it seems, cannot handle the task of birth as they are often destroyed in the process of labor.

Although uncomfortable, I believe that these types of fiction allow our culture to wrestle with pertinent questions about our relationships to our bodies. Although some scenarios seem impossible (at present, for example, biological males are unable to give birth to offspring), the idea that technology might eventually intervene and allow men to carry to babies to term does not seem to be out of the question. Should such a day come, we can refer back to fiction like that of Octavia Butler in order to better articulate our views on reproduction and sex as we come to see that what we have long considered “natural” is, in fact, merely socially constructed.

Something in the Air Tonight

Something in the Air Tonight – PowerPoint Slides

1660 was a year of great upheaval in England, with the beginning of the English Restoration marked by the ascendancy of Charles II to the throne. That same year, another event—lesser known, although no less revolutionary—occurred, which would affect the future of Science forever: the invention of air.

1660 was a year of great upheaval in England, with the beginning of the English Restoration marked by the ascendancy of Charles II to the throne. That same year, another event—lesser known, although no less revolutionary—occurred, which would affect the future of Science forever: the invention of air.

Now I don’t mean that someone found a container and mixed together 78% Nitrogen, 21% Oxygen, and some other stuff. Air as a gas had existed for millennia. And I don’t mean air as an idea or concept. Rather, I mean the invention of air as an object of inquiry—something that could be studied and was worthy of such scrutiny.

Using the recently invented vacuum pump as an experimental apparatus, Robert Boyle published a book called New Experiments Physico-Mechanicall, a volume that aimed to describe the properties of air. Although this milestone may seem somewhat uninteresting to non-science geeks, the thoughts forwarded in this work formed the cornerstone of Boyle’s Law, which would later become incorporated into our fundamental understanding of how gasses behaved in closed systems. In short, Boyle’s publication helped to change the way in which we saw the world, rendering the once-invisible apparent, if still ephemeral.