Like So Much Processed Meat

“The hacker mystique posits power through anonymity. One does not log on to the system through authorized paths of entry; one sneaks in, dropping through trap doors in the security program, hiding one’s tracks, immune to the audit trails that we put there to make the perceiver part of the data perceived. It is a dream of recovering power and wholeness by seeing wonders and not by being seen.”

—Pam Rosenthal

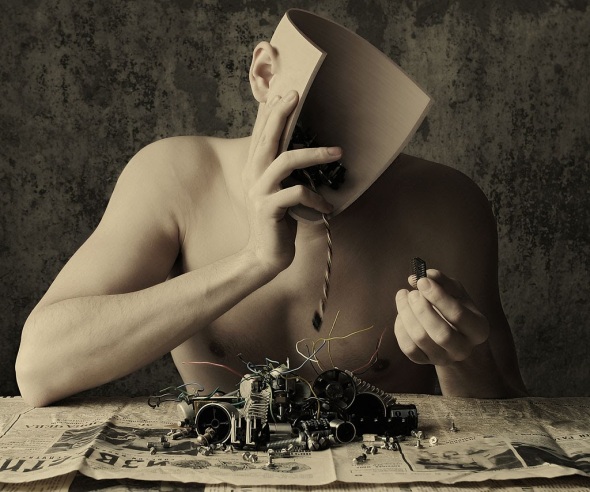

Flesh Made Data: Part I

This quote, which comes from a chapter in Wendy Hui Kyong Chun’s Control and Freedom on the Orientalization of cyberspace, gestures toward the values embedded in the Internet as a construct. Reading this quote, I found myself wondering about the ways in which identity, users, and the Internet intersect in the present age. Although we certainly witness remnants of the hacker/cyberpunk ethic in movements like Anonymous, it would seem that many Americans exist in a curious tension that exists between the competing impulses for privacy and visibility.

Looking deeper, however, there seems to be an extension of cyberpunk’s ethic, rather than an outright refusal or reversal: if cyberpunk viewed the body as nothing more than a meat sac and something to be shed as one uploaded to the Net, the modern American seems, in some ways, hyper aware of the body’s ability to interface with the cloud in the pursuit of peak efficiency. Perhaps the product of a self-help culture that has incorporated the technology at hand, we are now able to track our calories, sleep patterns, medical records, and moods through wearable devices like Jawbone’s UP but all of this begs the question of whether we are controlling our data or our data is controlling us. Companies like Quantified Self promise to help consumers “know themselves through numbers,” but I am not entirely convinced. Aren’t we just learning to surveil ourselves without understanding the overarching values that guide/manage our gaze?

Returning back to Rosenthal’s quote, there is a rather interesting way in which the hacker ethic has become perverted (in my opinion) as the “dream of recovering power” is no longer about systemic change but self-transformation; one is no longer humbled by the possibilities of the Internet but instead strives to become a transformed wonder visible for all to see.

Flesh Made Data: Part II

A spin-off of, and prequel to, Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009), Caprica (2011-2012) transported viewers to a world filled with futuristic technology, arguably the most prevalent of which was the holoband. Operating on basic notions of virtual reality and presence, the holoband allowed users to, in Matrix parlance, “jack into” an alternate computer-generated space, fittingly labeled by users as “V world.”[1] But despite its prominent place in the vocabulary of the show, the program itself never seemed to be overly concerned with the gadget; instead of spending an inordinate amount of time explaining how the device worked, Caprica chose to explore the effect that it had on society.

Calling forth a tradition steeped in teenage hacker protagonists (or, at the very least, ones that belonged to the “younger” generation), our first exposure to V world—and to the series itself—comes in the form of an introduction to an underground space created by teenagers as an escape from the real world. Featuring graphic sex, violence, and murder, this iteration does not appear to align with traditional notions of a utopia but might represent the manifestation of Caprican teenagers’ desires for a world that is both something and somewhere else. And although immersive virtual environments are not necessarily a new feature in Science Fiction television, with references stretching from Star Trek’s holodeck to Virtuality, Caprica’s real contribution to the field was its choice to foreground the process of V world’s creation and the implications of this construct for the shows inhabitants.

Seen one way, the very foundation of virtual reality and software—programming—is itself the language and act of world creation, with code serving as architecture. If we accept Lawrence Lessig’s maxim that “code is law”, we begin to see that cyberspace, as a construct, is infinitely malleable and the question then becomes not one of “What can we do?” but “What should we do?” In other words, if given the basic tools, what kind of existence will we create and why?

Running with this theme, the show’s overarching plot concerns an attempt to achieve apotheosis through the uploading of physical bodies/selves into the virtual world. I found this series particularly interesting to dwell on because here again we had something that recalls the cyberpunk notion of transcendence through data but, at the same time, the show asked readers to consider why a virtual paradise was more desirous than one constructed in the real world. Put another way, the show forces the question, “To what extent do hacker ethics hold true in the physical world?”

[1] Although the show is generally quite smart about displaying the right kind of content for the medium of television (e.g., flushing out the world through channel surfing, which not only gives viewers glimpses of the world of Caprica but also reinforces the notion that Capricans experience their world through technology), the ability to visualize V world (and the transitions into it) are certainly an element unique to an audio-visual presentation. One of the strengths of the show, I think, is its ability to add layers of information through visuals that do not call attention to themselves. These details, which are not crucial to the story, flush out the world of Caprica in a way that a book could not, for while a book must generally mention items (or at least allude to them) in order to bring them into existence, the show does not have to ever name aspects of the world or actively acknowledge that they exist.

Until It’s Vegas Everywhere We Are

In 1954, psychologists James Olds and Peter Milner conducted a landmark experiment in the field of Behaviorism: implanting electrodes into rats, Olds and Milner allowed the animals to stimulate the pleasure centers of their brains via a lever. Depressing the control up to 700 times a day, the allure of the stimulation was so strong that, given a choice between pleasure and food, rats eventually died from exhaustion.

In 1954, psychologists James Olds and Peter Milner conducted a landmark experiment in the field of Behaviorism: implanting electrodes into rats, Olds and Milner allowed the animals to stimulate the pleasure centers of their brains via a lever. Depressing the control up to 700 times a day, the allure of the stimulation was so strong that, given a choice between pleasure and food, rats eventually died from exhaustion.

Initial reactions to this scenario often include a measure of shock and disbelief as individuals try to make sense of what they observe. Why would an animal literally pleasure itself to death? Although we as humans—and supposed exemplars of rationality—might make different choices in a similar situation, the lesson to learn from the Olds and Milner study is that the pursuit of pleasure can be a powerful influence on our lives.

The continued resonance of the Olds and Milner experiment is perhaps most evident in the appearance of “click bait.” Typically relying on provocative visual elements (e.g., a headline and/or image), the concept of click bait adopts strategies and logics gleaned from advertising as it employs old models that form a direct correlation between value and number of views. Inhabiting a space at the intersection of attention, pleasure, and economic forces, the concept of click bait represents an interesting object of inquiry as we read about notions of visibility.

The continued resonance of the Olds and Milner experiment is perhaps most evident in the appearance of “click bait.” Typically relying on provocative visual elements (e.g., a headline and/or image), the concept of click bait adopts strategies and logics gleaned from advertising as it employs old models that form a direct correlation between value and number of views. Inhabiting a space at the intersection of attention, pleasure, and economic forces, the concept of click bait represents an interesting object of inquiry as we read about notions of visibility.

Click bait does not invite us to linger, to savor, or to contemplate; click bait entreats us to look but not to see or to imagine, encapsulating Nicholas Mirzoeff’s understanding of visuality as a force that is determined to impose a singular unified vision of the world on multiple levels. Take online slideshows as an example of notorious forms of click bait that rob us of the ability to curate our own collections and to develop our own connections between things. Visual displays such as these provide tangible examples of Mirzoeff’s position that visuality operates through classifying, ordering, and naturalizing—an assertion that offers a certain amount of overlap with the role that language plays in our experiences as it mediates the transformation from sensation into perception. Here, the price that we pay for a brief moment of pleasure is the loss of our imagination—we not only dampen our ability to see other realities but fundamentally inhibit our ability to believe that they can even exist. Click bait represents an entity that screams for our attention, offering a fleeing moment of pleasure in exchange for the opportunity to subvert our vision to its purposes as it directs us where to look.

Wrestling with these very notions of sight and seeing, Kanye West’s music video for “All of the Lights” speaks to the way in which stimulation and novelty has become increasingly integrated into the everyday experience of urbanized individuals.

The first viewing of West’s video is often difficult as viewers are confronted with frenetic visuals that invoke the light-filled cityscapes of Tokyo, Times Square, and Las Vegas. And yet, what strikes me is just how readily one becomes attuned to a display that boasts a prominent seizure warning.[1] What does this suggest about the way in which we have been trained to respond to visual stimuli in general and to incessant calls for our attention in particular? Or, perhaps more frighteningly, just how quickly we can habituate ourselves into unseeing.

“All of the Lights” is an interesting cultural artifact for me because it also wrestles with these notions of seeing and being seen through the lyrics of the song itself: concerned with the attempts of a parolee to see his daughter (and for his daughter to see him), the song (unwittingly) builds upon Mirzoeff’s position on the relatedness between autonomy and sight.[2] And yet the song goes further as it calls attention to situations that cultural outsiders might willfully refrain from seeing. “Turn up the lights in here, baby / Extra bright, I want y’all to see this,” the song implores as it endeavors to realize Mirzoeff’s suggestion that visuality be countered through the presentation of alternate forms of realism. Additionally, the sequence pays homage to the opening credits for Gaspar Noe’s Enter the Void, a movie that plays with perspective and perception, continually reminding us to pay attention to the fact that we are paying attention.[3]

This sort of critical self-reflection is, as Cathy Davidson notes in her book Now You See It, a helpful reminder that we have been trained to pay attention to particular facets of the world—mistakenly inferring that these elements constitute the world in its entirety—at the expense of others. Davidson points to the structural and systematic ways in which we are socialized to pay attention to, and thus value, particular objects, ideas, and actions over others. From family, to school, to politics, institutions shape what is worthy of attention and therefore what are values are; attention, then, is not just about what we see but also how we see it.

Chris Tokuhama

[1] Although difficult to watch in its entirety, Enter the Void’s title sequence is particularly memorable for the way in which it disrupts the viewing process and dislocates the viewer as foreshadowing for the experience that follows.

[2] On page 25 of The Right to Look Mizroeff writes, “By the same token, the right to look is never individual: my right to look depends on your recognition of me, and vice versa.”

[3] Similarly, I think that the opening scenes of American Horror Story: Asylum (https://www.facebook.com/americanhorrorstory/app_216209925175894) perform a similar function, which ties into the season’s overall theme of truth/reality. The thing that the show makes evident is the way in which our interaction with the world is intimately tied to our perception of it.

Secrets and Li(v)es

In retrospect, it was rather obvious: I was intrigued by Cultural Studies before I even knew what it was. My fascination with PostSecret—a site that began as a public art project wherein people anonymously mailed in secrets on postcards—began in early 2005, particularly timely given that I was just about to graduate from college and was feeling no small amount of anxiety about what would become of my life. Beyond an emotional connection, however, I also loved looking at the way in which the simple declarative statements combined with typography and associated images to produce a rather powerful artifact; the choices that people made in displaying their secrets—these innermost thoughts—fascinated me and I started down my path toward becoming a sort of amateur semiotician.

Over the years, the site has floated around in my head but one of the foundations of the project/website also serves as one of its greatest barriers to study: the anonymous submission process. All postcards are sent to an intermediary, Frank Warren, who selects and uploads the images to the site—this means that the original authors are impossible to study without violating users’ trust (and possibly a few laws). As a result, I cannot ascertain who feels compelled to create a postcard and, at times, that failure troubles me for these are the people who most need support.

I don’t mean to imply that I wish to know exactly who wrote which card but I would love to get an analysis of the demographics for the makers. What types of people feel the need to create cards and send them in? Are these individuals who feel as though they cannot express their voice through other channels? How does the population of makers compare to the population of readers? One might argue that there is likely to be a certain amount of overlap but the very notion that one set is driven to craft something is intriguing to me. And even if we were able to recruit study participants (ignoring likely IRB complications for a moment), we would have to suspect a kind of volunteer bias, particularly given the nature of the material being disclosed on the site.

So instead I endeavor to study the way in which the site and its associated products (museum exhibits, books, and speaking engagements) intersect with, and create, culture. The project raises a number of questions for me, specifically how it reflects our current culture of confession. In particular, I often wonder how the current state of media might have affected the success of a movement like PostSecret.

So instead I endeavor to study the way in which the site and its associated products (museum exhibits, books, and speaking engagements) intersect with, and create, culture. The project raises a number of questions for me, specifically how it reflects our current culture of confession. In particular, I often wonder how the current state of media might have affected the success of a movement like PostSecret.

Growing up, I remember watching the first seasons of The Real World and Road Rules on MTV and was always entranced by the confessional monologues. As a teen, the confessionals possessed a conspiratorial allure, for I was now privy to insider information about the inner workings of the group. However, looking back, I wonder if this constant exposure to the format of the confessional has changed the way that I think about my secrets.

The confessional has become rather commonplace on the slew of reality shows that have filled the airwaves of the past decade and the practice creates, for me, an interesting metaphor for how Americans have to come to deal with our struggles. As confessors sit in an isolation booth, they simultaneously talk to nobody and to everybody; place this in stark contrast to the typical connotation of “confession” and its associated images of an intimate discussion with a priest.

PostSecret, in some ways, is merely a more vivid take on St. Augustine’s seemingly far-removed literary testimony in Confessions and yet also an extension of the modern practice of mediated confession: we hold our secrets in until we get the chance to broadcast them across media channels. We exist in a culture that has transformed the act of confession into a spectacle—we celebrate press conference apologies and revelations of sexual orientation make the front page. Has our desire for information transformed us into a society that hounds after secrets, compelling others to confess the things they hope to keep to themselves? Are secrets worth something only in their threat to expose or reveal? What does this whole practice of secret keeping tell us about the way that we relate to ourselves and to others? We oscillate between silence and shouting—perhaps we’ve forgotten how to talk—and we are desperate to make connections, to find validation, and to be heard. Are we so consumed with tending to our own secrets and revealing those of others that we have, in some ways, become nothing more than a site of secrets? How does this intersect with notions of empathy and narcissism?

PostSecret, in some ways, is merely a more vivid take on St. Augustine’s seemingly far-removed literary testimony in Confessions and yet also an extension of the modern practice of mediated confession: we hold our secrets in until we get the chance to broadcast them across media channels. We exist in a culture that has transformed the act of confession into a spectacle—we celebrate press conference apologies and revelations of sexual orientation make the front page. Has our desire for information transformed us into a society that hounds after secrets, compelling others to confess the things they hope to keep to themselves? Are secrets worth something only in their threat to expose or reveal? What does this whole practice of secret keeping tell us about the way that we relate to ourselves and to others? We oscillate between silence and shouting—perhaps we’ve forgotten how to talk—and we are desperate to make connections, to find validation, and to be heard. Are we so consumed with tending to our own secrets and revealing those of others that we have, in some ways, become nothing more than a site of secrets? How does this intersect with notions of empathy and narcissism?

These questions are, of course, not unique to PostSecret but I think that the project does offer a slightly different entry point into a community that can be secretive. Moreover, the development of an iPhone app might cause us to reflect on what is represented by the barrier of physically making and sending a postcard—does convenience lower the barrier to what might be considered a “secret”? As of yet, there does not seem to be a noticeable difference between the secrets sent in through the postal mail and those generated by the app but this might be due to the fact that secrets are screened and selected prior to their public display.

On a Mission?

Consumables are the product of how a culture understands its relationship to the world around it (although it should be noted that they are not the only way) with items following an underlying logic about the way in which the world works and often fulfilling a perceived need for consumers. Manufactured products, then, are not just products but also serve as tangible artifacts of entire ideological structures: “products” are the result of, and indicative of, a specific type of relationship between consumer and consumable and it is this relationship that speaks to the underlying ideology. Accordantly, it does not seem out of the question to argue that the trade of products also allows for the transmission of values.

Consumables are the product of how a culture understands its relationship to the world around it (although it should be noted that they are not the only way) with items following an underlying logic about the way in which the world works and often fulfilling a perceived need for consumers. Manufactured products, then, are not just products but also serve as tangible artifacts of entire ideological structures: “products” are the result of, and indicative of, a specific type of relationship between consumer and consumable and it is this relationship that speaks to the underlying ideology. Accordantly, it does not seem out of the question to argue that the trade of products also allows for the transmission of values.

Although this process is most likely apparent when trading groups are most dissimilar (e.g., when trade is first established between two communities), we can continue to glimpse aspects of this process occurring in our highly globalized Western societies. On one level, we have products that are closely connected to our understanding of culture that make their values highly visible—fashion, for example, transmits ideas through aesthetic (e.g., color, structure, cut, textile choice, etc.) that reflect how a particular group of people see themselves. Beyond just notions of status or ornamentation, we might also consider how a group’s use of materials like fur or toxic dye also reveal how a culture positions itself relative to other things in the world: things in the environment are tools or resources to be used in service of humans.

Certainly, cultural products like fashion, film/television, art, music, comics, and literature all contain a fairly visible sensibility that is easier to recognize (if not isolate) and discuss. Take, for example, the highly visible way in which Disneyland/Disneyworld portray a very particular understanding of the world through the ride “It’s a Small World.” Getting past anger that may arise from stereotypes or characterizations, we see that the animatronic dolls depict the world through a set of Western eyes (which, given their locations and likely audience makes a certain amount of sense). But also fascinating is the way in which this ride is reproduced around the world and how those iterations help to reveal the ways in which a product can not only reflect, but produce, ways in which we see ourselves in our surroundings.

Here we can look at how a likely Western family is experiencing China’s take on Disney’s version of countries like China—incredibly rich, to say the least. But we can also think about how theme parks like Disneyland/Disneyworld represent a physical sort of colonization in countries like Japan and France. Colonization, it seems, has become less about invasion and domination through force and more concerned with buying into a particular ideology through consumption; put another way, our missionaries are no longer people but products.

But we can also consider how the development of the Internet has allowed for an incredible flow of information around the world. While there are certainly positive aspects to this development (e.g., the potential for access to information and the creation of different channels for individuals to be heard), we must also grasp with the very real concerns that a free flow of information also creates a competition for survival amongst the ideas of the world. In an ideal world, this sort of competition would be the “survival of the best,” but increasingly it seems as though it is the “survival of the loudest.”

As we discussed last week, English has an incredible influence on the types of articles and information that are published in scientific journals (the influence is less in journals that concern Natural Science but English seems to continue to exert a large presence). Although some of my classmates may be able to speak to this in more nuanced ways, I also wonder about the effect that the dominance of English has on the ways in which we understand the world. I am not fluent in another language but find that when I try to speak in Japanese, I need to think in Japanese and that this causes me to adapt a different set of behaviors and thoughts. If this sort of shift occurs on a larger scale, we then not only have to question the content of the information being circulated around the world but also the form in which it manifests.

As we discussed last week, English has an incredible influence on the types of articles and information that are published in scientific journals (the influence is less in journals that concern Natural Science but English seems to continue to exert a large presence). Although some of my classmates may be able to speak to this in more nuanced ways, I also wonder about the effect that the dominance of English has on the ways in which we understand the world. I am not fluent in another language but find that when I try to speak in Japanese, I need to think in Japanese and that this causes me to adapt a different set of behaviors and thoughts. If this sort of shift occurs on a larger scale, we then not only have to question the content of the information being circulated around the world but also the form in which it manifests.

Role-Playing Games

Manipulation seems like such a dirty word.

And yet, as a Social Psychology student, my books were filled with terms like “influence,” “persuasion,” “schema activation,” and “behavior modification”—apparently, my undergraduate years were spent learning how to constrain the range of salient choices available to others. Over the years, my work has evolved, but I often think back to my initial interest in the subject and how it was closely linked to the work of Goffman, although I was not able to articulate the connection at the time.

As a former admission officer, the implications of self-presentation are often glaringly obvious for anyone who has set foot inside of a high school: from stereotypical cliques to personal dress and demeanor, students broadcast an incredible number of messages as they attempt to manufacture, consolidate, express, and identify their senses of self. Goffman suggests that this exchange of information can occur through processes that the actor willfully controls (or is perceived to) and those that are communicated without conscious knowledge. Further exploring the relationship between audience, message, and source, we encounter the work of Gross who labels sign-events either “natural” or “symbolic.” Although natural sign-events undoubtedly have a measure of usefulness when it comes to interacting with the physical world around us, the symbolic seem most relevant to Goffman’s discussion of interpersonal interaction and the nature of socially-constructed reality.

Although we might discuss the potential of fashion to figure into this process, I tend to think about it more broadly in terms of information and power; as Goffman mentions, a constant tension exists between actor and audience as both parties attempt to ascertain who knows what about whom. And, in many ways, possessing a more complete picture of the situation allows one to better dictate the nature of the interaction, for understanding the rules of the game (i.e., Goffman’s “working consensus”)—or even knowing that you are playing one in the first place!—leads to more desirable outcomes, particular when we are trying to deceive others about who we are.

There seems to be a biological imperative for deception, as the act, in its many forms, can serve to reduce the cost of obtaining something of value (e.g., goods, services, protection, contentment, etc.), but while animals have traditionally employed this tactic for self-preservation (e.g., mimicry), human beings have taken the practice to more complex levels. Perhaps unsurprisingly, as we slowly exit the Age of Information, many current deceptive practices revolve around the manipulation of knowledge. Online, we might “fudge” our profile pictures in an attempt to lessen the rejection that we so desperately seek to avoid in real life or we might alter a personal characteristic in order to test the waters of a new identity in an environment that allows us to process anxiety and judgment from the safety of our homes. I often wonder how those of us who use social media cultivate our profiles, tending to them like gardens: to what extent do we fetishize our online presence, letting it define us instead of the other way around? It would seem that while the relative ease of online deception confers us some cognitive defense, it also threatens to overwhelm us with delusion.

We lie to others and, perhaps even worse, lie to ourselves.[1] We look outward for acceptance and affirmation instead of delving inward to confront the deepest parts of ourselves. Technology has allowed us, as individuals, to connect over vast differences and afforded us many opportunities that we might not otherwise have; yet, in some ways, it has also left us disconnected from the things that (arguably) matter the most.

[1] Although this is a separate topic, I am incredibly interested in the ways in which perform acts of self-deception, as I think that these have the potential to harm us in spectacular ways. Using Goffman’s theater metaphor, I think it is fascinating to consider what happens when the “backstage” is really just the “front stage” for our inner psyche.

I Can Be Your Hero, Baby

The world is a dangerous place not because of those who do evil but because of those who look on and do nothing.

—Albert Einstein

These words, known to most who have ever encountered a course on Ethics, set the tone for HBO’s documentary Superheroes, which profiles individuals involved in the Real Life Superhero movement. Although there is truth to Einstein’s words—for failing to stop injustice can represent a form of evil—the question becomes one of perspective: in a simplified system that includes three perceived parties (victim, perpetrator, and savior), the solution seems rather obvious for we know what we should do, regardless of whether we actually intercede. But what happens when we situate the same concept in the context of a community or society? Vigilante justice leads to societal breakdown as we each enforce our own moral codes.

It is for this reason that I’m often suspect of these individuals who undoubtedly have good intentions. Although it is easy to judge and express disdain for grown adults who seem out of touch with society, the fringe often worry me. I’m not so much concerned that they do not look like I do or that they “dress up,” but rather worry because they do not play by my rules. And, ultimately, isn’t it just a short hop from there to a defining characteristic of a villain? Regardless of if the individual in question is a nuisance, helpful, or a menace, the fact that he or she has checked out of the system that you live in raises should raise some red flags.

The invocation of Kitty Genovese is also perhaps unsettling because it misses the forest for the trees. Again, on an individual level, the story is perhaps one that inspires you to action, but donning your gear does nothing to address the larger issue of apathy, the bystander effect, or the diffusion of responsibility (whatever you choose to call it).

And although it has not yet come to this, what if super villain groups formed in opposition to these real life superheroes? Not just gangs or the mafia, but groups of individuals who preferentially targeted those who would do good? The streets would devolve into a sort of war zone with casual citizens and public property caught in the crossfire. I suspect that these superheroes only survive because nobody is actively trying to hunt them.

This of course raises the notion of who should be a superhero.

I certainly get some of the impulse to become a superhero, transforming yourself into a powerful figure as you draw out the traits in yourself that you most admire. In many ways, I am all for that. And I also recognize the power and prestige that comes from donning a mask or a cape or a costume—these accouterments are symbols of your office and confer power, status, and meaning.

My constant struggle, however, is to walk the fine line between seeing the everyday as worthy of superhero status while fighting the impulse to disconnect from the system. In the best possible world, everyone is a superhero and everyone works together (using the particular talents that we each have) to contribute to a whole. In some ways, perhaps, similar to Communism (and we know how that went), but never with the expectation that you are going to necessarily get something for your efforts. You work because you believe in the system and because you place hope in your community.

And is this also just another symptom of a society that has become desensitized to extreme and spectacle? That we believe that, in order to be empowered, we have to become superheroes? Has the groundwork been laid by Stan Lee’s shows, which have “trained” real life superheroes? Where do we draw the line between a good citizen (one who is, perhaps, civically engaged!) and having to create a superhero persona? Ultimately, why can’t we integrate the actions that we would undertake as a superhero into our everyday sense of self?

The old questions that were first raised with virtual selves and MMORPGs continue to haunt me: are these people who are compensating for a feeling of powerlessness elsewhere in their lives? In some ways, their actions seem to be a direct response to the inefficiency of law enforcement but I suspect that it runs deeper than that. If you still believed in the system, wouldn’t you fight for reform instead of doing it on your own? Is there something just viscerally satisfying about putting yourself in potential danger that adds to the equation?

Fears vs. Dreams

She cuts herself, using the blade to write “FUCK UP” large across her left forearm.

Looking back, it would have seemed quite obvious: although I’ve now grown into someone studying for a graduate degree in Communication, I have always been enthralled by the power of narrative. As a child, mythology was my go-to, with stories of ancient cultures giving me—a kid with a short cultural history in America—a sense of place. I’ve since grown into someone who has embraced storytelling as a means of information transmission, learning to see identity as a complicated real-time narrative infused with performance. I think about the world in terms of stories being written, by ourselves as well as by others.

And perhaps this is why I tend to take issue with It Gets Better. Although a valuable message, the project has always sort of rubbed me the wrong way as it seems to suggest that others will write the story of your life for you. Things will get better, it says, somewhere and someday (that’s not here). Things will get better, but you will not. My gut is always to flip that and say that things will get better because you will make them better. You get to write the story of your life and, in so doing, learn the hard lesson that the story is never about you. Well, not just you, anyway. Your story intersects with millions of others and while you are the center of your story, you are a bit character in many others. You learn humility, but also that your presence makes a difference. Given my affinity for storytelling, it makes sense, then, that projects like PostSecret and To Write Love on Her Arms hit home for me.

I am particularly in love with TWLOHA’s newest project that asks people to define their greatest fear and hope. In so many ways, this is exactly what I hope to accomplish by studying horror—although the two aren’t always directly connected, I do believe that they stem from the core of our beings. Articulating both of those concepts is the first step on a journey that can lead to nothing but goodness. Articulating both of those is how you become a fighter, an activist, and a healer.

The video puts forth a series of statements:

This world needs you.

Your family needs you.

Your friends need you.

Your children—maybe someday, maybe now—need you.

But, to that, I would add: You need you.

Fight.

EVE Online

A profile piece in PC Gamer sparked a class discussion on the ethics of ramifications of virtual murder in EVE Online, causing me to wonder further about issues of ownership in MMORPGs. Given the situation described in the assigned reading, one might very well make the argument that much fuss was raised over Negroponte’s bits, essentially a meaningless commodity in and of itself. By all accounts, however, the sense of loss felt by victims of online theft seems very real. In order to better explain this phenomenon, I would suggest that what is lost is not just the item, but the representation of that item; badges, achievements, and trophies have become a method for us to gauge ourselves against one another and provide a palatable way for us to measure up. Status and identity have coalesced into (worthless if meaningful?) bytes, and the stealing of these items represents a loss in our sense of self. Can we ever go back to valuing what the badges are supposed to represent? Can we ever go back to an appreciation for having had an experience?

In a broader sense, the question of possession becomes increasingly relevant as we also seem to be moving toward a culture in which the lines of ownership have suddenly become much blurrier. We freely (if perhaps unknowingly) release personal data online, engage in a continual process of remix through sites like YouTube, and have begun to realize the power of crowdsourcing. Facebook owns the data that we upload and yet we bristle when the company chooses to use that information in a way that violates our assumptions regarding fair use. Where and why do we draw the line regarding ownership?

Going back to EVE Online as an example of an MMORPG, why is that we feel that anything in the game is ours in the first place? Put another way, all of the loot/drops/rares are the property of the game company—although we may have them temporarily in our inventories, we do not necessarily “own” them. Do we unavoidably apply the principles gleaned from real life (e.g., physically possessing an object means that we, in some way, own it) to the online realm? As we increasingly integrate virtual worlds into our lives, will we develop new rules and/or standards regarding the ownership of information as opposed to property? Is information in fact property and, if so, to what extent?

Ethnicity

Issues of ethnicity, another important (and perhaps arguably fundamental) aspect of identity, do not solely manifest in online spaces and although their virtual presentation confers a set of challenges that remain unique to that environment, lessons from real life racial politics can still apply.

Before proceeding, it should be noted that I draw distinctions between the terms “ethnicity” and “race,” although they are often used interchangeably in literature and vernacular. A result of my background in Biology, I conceptualize race in terms of biologically derived aspects like skin color while I define ethnicity as comprising of cultural elements that include locale, religious practices, and/or traditions (i.e., the physical layer versus the social layer). Given this schema and their dependence on the presentation of physical traits, online issues of racial identity, then, might be different in MUDs/MOOs and MMORPGs, as the latter potentially possesses fewer graphical constraints. Defining oneself as “African American,” for example, has different consequences in the various constructs considering the available resources available to players to create such an identity—given a lack of appropriate visual cues, using “African American” in a MOO might be interpreted as racial or ethnic identity (or, more likely, as a confluence of both), presenting an ambiguity that a visualized avatar does not.

Yet, regardless of our individual definitions of “race” and “ethnicity,” we can examine some of the various real world strategies employed to mediate racial differences in order to obtain overarching lessons and warnings. Looking at metaphors for ethnic diversity in the real world, we often hear the term “colorblind,” indicating that a subject (e.g., a person, a group, or an institution) professes not to see the differences presented by various racial groups. Although a good-hearted gesture, “colorblind” and the related concept of “melting pot” ultimately serve to essentially erase the notion of race by subsuming all individuals into the dominant racial or ethnic group; we no longer see color because we are all the same color. A much more difficult model has been introduced and labeled as the “fruit salad,” which attempts to encapsulate the idea that each ethnicity brings something different to the mix and that the final product should celebrate these differences. Translating this to the online sphere, it seems only prudent to encourage individuals to understand their virtual ecology, respecting the various niches and roles that other users might fulfill or perform.

The Future of Reputation

At its heart, Daniel Solove’s book The Future of Reputation is a frank discussion about the ways in which information aggregation, transmission, and expression affect online and offline social structures. While Solove recognizes that the Internet has undoubtedly conferred benefits to users, he also notes significant challenges posed by the architecture of online media and attempts to make readers aware of the slowly shifting changes within American (and, to some extent global) culture.

Although not necessarily central to Solove’s position, a basic understanding of computer-mediated communication is essential for appreciating the author’s later arguments regarding privacy and reputation. One point to consider, for example, is that a number of factors have increased the amount of information accessible to the average person (e.g., lowered barriers to participation, increasingly democratic access to the Internet with regard to both cost and tools, and the improvement of infrastructure) and, perhaps more importantly, the ability of the individual to produce content that is readily displayed on the Internet. The net result of this activity is an increase in the amount of information that is available online and the sheer mass is something not readily comprehended by individual users who do not have a strong sense of the bigger picture. To be entirely fair, this conclusion is not necessarily anomalous given that most users (1) do not have an internalized bird’s eye view of the structure of the Internet and (2) most likely do not have a valid/tangible frame of reference in real life. Nevertheless, Solove argues that the unchecked flow of information can result in incredibly damaging consequences—what we don’t see can definitely hurt us.

Take, for example, Solove’s discussion of social norms and behavior enforcement via shaming as a particularly salient case where unseen forces can present a very real threat; it is precisely because norms are hidden that they possess an enormous potential for havoc. Solove argues that social norms in real life have been fairly well established, even when they revolve around relatively recent advances in technology like cellular phones. Put another way, these are the sort of “unwritten rules” that govern social conduct in societies and may certainly differ based on group members and situational context; a norm is, quite simply, a standard of behavior that stems from mutual agreement as opposed to a sanctioned law (although laws, as Solove notes, may very well derive from social norms).[1] Conversely, however, behavioral norms in online life are still being formulated, which leads to confusion, misinformation, and unexpected consequences. Littered throughout Solove’s book are examples where an attempt to enforce social norms through online media careened out of control—although individuals anticipated a particular reaction to their outrage, intending, perhaps, to gain sympathy or commiseration, the end result was a firestorm of activity that quickly magnified into potentially treacherous proportions as audiences became vigilantes. The problem, Solove suggests, arises when we change the context for presented information without providing sufficient indicators regarding the surrounding conditions.[2] In essence, we take the information gleaned through a snapshot and attempt to build a global explanation that attempts to answer “how” or “why” a particular situation exists.

This change of context has important ramifications for discussions of the public/private continuum, which Solove notes has historically been considered a binary equation. Most notably, Solove argues that a gradation of public and private exists based on, among other things, reasonable expectation of privacy in a given situation. Connecting this back to information flow, Solove also notes that notions of privacy also exist in social networking services—indeed, who hasn’t heard about Facebook’s ongoing struggles with privacy issues?—and suggests that a closer examination of social network structures might offer some insight into considerations of privacy. For Solove, an understanding of the relationships between individuals in a network is a key component of recognizing the difference between secrecy and confidentiality (2007).

Finally, Solove weaves a discussion of reputation throughout his book, demonstrating how the concept can be construed as a social construct that is based upon an amassment of information. As such, the problems that plague information networks on the Internet greatly affect reputation construction, maintenance, systems, and management. For example, the aforementioned flood of information (both good and bad) has somewhat dire consequences for reputation as accurate statements mingle with the incorrect or defamatory in online spaces until the two become indistinguishable. Moreover, the negative pieces of information are able to propagate and linger on the Internet with relatively little concern for the resulting damage; at its worst, the relative anonymity of the online world allows people to eschew personal responsibility for their actions and occasionally promotes vicious rumor mongering that only serves to satiate our basest desires as humans.

[1]Solove, D. J. (2007). The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. For further discussion, see Ferdinand Tonnies’ discussion of Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft.

[2] I would also suggest that even if sufficient indicators were included, audiences might still be subject to the Fundamental Attribution Error (i.e., the preferential explanatory heuristic that serves to overemphasize personality characteristics of the subject in deference to possible environmental factors).

Ushahidi

Generally speaking, advances in technology have not only allowed us to streamline existing processes but have also caused us to radically reconsider traditional modes of operation. As individuals and societies become increasingly familiar with technology, and its use becomes seamlessly integrated into everyday life, room for striking innovation develops. In particular, mobile-based applications represent an area with interesting implications for growth.

In response to Kenya’s post-election violence in 2008, an organization called Ushahidi developed a simple cross-platform tool that would allow citizens to report incidents of intimidation as they happened via text/picture message or the Internet. By focusing on mobile phone technology, developers tapped into the most pervasive technology available in the developing country; mobile phones also provided additional elements such as ease of access and location-specific crowdsourced data. Amazingly, Ushahidi developed a simple open-source tool that aggregated reports of incidents and displayed them on a Google map—the genius was not necessarily in this mash up, although visualization allowed for new ways to understand the problems plaguing the country, but in the idea that this program could be employed anywhere for almost any type of crisis situation from monitoring swine flu to the recent Haitian earthquake.

Ushahidi, much like Twitter, has an advantage in that it represents a bottom-up model of information integration and reports come directly from the people being affected; institutions such as Ushahidi give people a voice, especially when the presiding government cannot be trusted. However, Ushahidi is not a success story merely because it has developed a new method to present knowledge, but because it has also allowed individuals to create a new system for manipulating it. Ushahidi has empowered citizens to become active participants in their communities and taught individuals how to leverage information in order to affect social, political, or economic change.

The Matrix

Lawrence Lessig’s words continue to haunt me. An avid fan of The Matrix, Lessig’s thoughts on the manipulation of code caused me to flash back to a particular moment near the end of the movie. For the majority of the film, Neo, the protagonist, has progressed in his training but is constrained by the fact that the Matrix is based on rules that can be bent, but seldom broken. However, after a resurrection—conferred by true love’s kiss!—Neo performs a physically impossible feat demonstrating a newfound mastery over his world. Fittingly, our first look at the world through Neo’s eyes after this event displays the virtual environment as code; to Neo, the world is nothing more than a string of symbols. One might argue that Neo’s rebirth has enabled him to see things as they really are (a sort of ultimate payoff of the red pill) and it is his understanding of the Matrix’s governing processes that affords him his powers. For a particular generation, The Matrix provides a highly visible example of Lessig’s position that code dictates law. Neo’s epiphany, visually laid out for audiences, allows observers to grasp Lessig’s theories—even if they might not be able to articulate what they have witnessed.

The implications of code have not change since the movie’s release. No longer the stuff of science fiction, code is affecting our real lives through seemingly mundane conduits like traffic signal regulation and the (perhaps) more surprising selling of online real estate; I still remember being fascinated by news of code from Ultima Online being auctioned in a live marketplace—here were parties that were willing to trade resources for (arguably useless) bits!

Currently, we continue to grapple with the navigation of these virtual spaces, made difficult by the notion that many do not understand the rules that govern our spaces. Augmented reality will further complicate this process as additional layers of code are overlaid upon our physical reality; wearable computing might change the ways that we deal with access, permission, and restrictions as we attempt to balance code and natural laws.

Cyberspace

Almost a year ago, Elizabeth Coleman, the president of Bennington College, gave a talk that challenged listeners to reconsider their views on the Liberal Arts. The current educational structure, Coleman argued, did not force students to engage in community-based thinking; specifically, students were not asked to question the types of worlds that they could be making, much less what types of worlds they should be making.

Given this perspective, Lawrence Lessig’s discussion of “is-ism” and cyberspace seems more apt (and also appears as a symptom of a larger issue). In Code 2.0, Lessig argues that a majority of the population accepts the Internet as it is, complete with all of its limitations and frustrations. Accepting the situation, we make the best of our surroundings and fail to consider that the current state of cyberspace might not be the best of all possible worlds. Importantly, Lessig advances the idea that the man-made structure of cyberspace shapes its functionality (a theme echoed in Biology as well); Lessig’s statement implies that we can change the nature of cyberspace if we alter the underlying foundational code.

Lessig’s also contrasts the US Constitution with the regulatory forces that govern cyberspace, noting differences in amendment processes between the two. While the Federal process contains checks and balances that aim to prevent abuse of power, the rules that govern cyberspace are somewhat more fluid. In short, average citizens could have more opportunities to effect change because they can more directly affect the structure of these online spaces.

Going back to Coleman’s point regarding civic involvement, one can foresee potential problems ahead for Americans if they continue to be relatively complacent with the regulation of cyberspace. With Internet usage being integrated firmly into citizens’ lives, it seems obvious that we should care about issues of regulation, content, and access but, unfortunately, we may simply may not have been taught to think along these lines.

You must be logged in to post a comment.