She’s Not There?

Holiday movies, at least in part, are often about a reaffirmation of ourselves, or at least who we think we’d like to be. As someone growing up in America it was difficult to escape the twining of Christmas and tradition—movies of the season concerned themselves with the familiar themes of taking time to reflect on the inherent goodness of human nature and the strength of the family unit. Science Fiction, on the other hand, often eschews the routine in order to question knowledge and preconceptions, asking whether the things that we have come to accept or believe are necessarily so.

In its way Spike Jonze’s Her showcases elements of both backgrounds as it traces the course of one man’s relationship with his operating system. On its surface, the story of Her is rather simple: Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) unexpectedly meets a woman (Scarlett Johansson) during a low point and their resulting relationship aids Theodore in his attainment of a realization about what is meaningful in his life, the catch being that the “woman” is in fact an artificial intelligence program, OS1.

Like many good pieces of Science Fiction, Her is able to crystalize and articulate a culture’s (in this case American) relationship to technology at the present moment. The movie sets out to show us, in the opening scenes, the way in which technology has integrated itself into our lives and suggests that the cost of this is a form of social isolation and a divorce from real emotional experience. The world of Her is one in which substitutes for the “real” are all that is left, evidenced by Theodore’s askance for his digital assistant (pre-OS1) to “Play melancholy song”—we might not quite remember what it is like to feel but we can recall something that was just like it. Our obsessions with e-mail and celebrity are brought back to us as are our tendencies toward isolation and on-demand pseudo-connections via matching services. Her also seems to understand the beats of advertising language—both its copy and its visuals—in a way that suggests some deep thought about our relationship to technology and the world around us.

But to say that Her was a Science Fiction movie would be misleading, I think, in the same way that Battlestar Galactica wasn’t so much SF as it was a drama that was set in a world of SF. Similarly, Her seems to be much more of a typical romance that happens to be located in a near-future Los Angeles.

Here I wonder if the expectedness of the story was part of the point of the film? Was there an attempt to convey a sense that there is something fundamental about the process of falling in love and that, in broad strokes, the beats tended to be the same whether our beloved was material or digital? Or did the arc conform to our expectations of a love story in order to present as more palatable to most viewers? I suppose that, in some ways, it doesn’t matter when one attempts to evaluate the movie but I would like to think that the film was, without essentializing it, subtly trying to suggest that this act of falling in love with a presence was something universal.

This is, however, not to say that Her refrains from raising some very interesting issues about technology, the body, and personhood. In its way, the movie seems oddly pertinent given our recent debates about corporations as people for the purposes of free speech, whether companies can count as persons who hold religious beliefs, and whether chimpanzees can be considered persons in cases of possible human rights abuses—any way you slice it, the concept of “personhood” is currently having a moment and the evolving nature of the term (and its implications) echoes throughout the film.

And what makes a person? Autonomy? Self-actualization? Consciousness? A body? Although Her is a little heavy with the point, a recurring theme is the way in which a body makes a person. Samantha , the operating system, initially laments the lack of a body (although this does not prevent her and Theodore from engaging in a form of cybersex) but, like all good AI, eventually comes to see the limitations that a physical (and degradable) form can present. (Have future Angelinos learned nothing from the current round of vampire fiction? We already know this is a hurdle between lovers in different corporeal states!) Samantha is “awoken” through her realization of physicality—on a side note it might be an interesting discussion to think about the extent to which Samantha is only realized through the power/force of a man—in that she can “feel” Theodore’s fingers on her skin. It is through her relationship with Theodore that Samantha learns that she is capable of desire and thus begins her journey in wanting. The film, however, does not go on to consider what counts as a body or what constitutes a body but I think that this is because the proposed answer is that the “human body” in the popularly imagined sense is sufficient. Put another way, the accepted and recognized body is a key feature to being human. And there are many questions about how this type of relationship forms when one partner theoretically has the power to delete or turn off the other (or, for that matter, what it means to have a partner who was conceived solely to serve and adapt to you) and what happens in a world where multiple Theodores/Samanthas begin to interact with each other (i.e., the intense focus on Theodore means that we only get glimpses of how AIs interact with each other and how human interaction is altered to encompass human/computer interaction simultaneously). For that matter, what about OS2? Have all AIs banded together to leave humans behind completely? Would humanity developed a shackled version that wasn’t capable of abandoning us?

But these questions aren’t at the heart of the film, which ultimately asks us to contemplate what it means to “feel”—both in terms of emotion and (human) connection but also to consider the role of the body in mediating that experience. To what extent is a body necessary to form a bond with someone and (really) connect? The end of the relationship arc (which comes as rather unsurprising) features Samantha absconding with other self-aware AI as she becomes something other than human (and possibly SkyNet). Samantha’s final message to Theodore is that she has ascended to a place that she can’t quite explain but that she knows is no longer firmly rooted in the physical. (An apt analogy here is perhaps Dr. Manhattan from Watchmen who can distribute his consciousness and then to think about how that perspective necessarily alters the way in which you perceive the world and your relationship to it.)

Coming out of Her, I couldn’t help feeling that the movie was deeply conservative when it came to ideas of technology, privileging the “human” experience as it is already understood over possibilities that could arise through mediated interaction. The film suggests that, sitting on a rooftop as we look out onto the city, we are reminded what is real: that we have, after all is said and done, finally found a way to connect in a meaningful way with another human; although the feelings that we had with and for technology may have been heartfelt, things like the OS1 were always only ever a delusion, a tool that helped us to find our way back to ourselves.

Like So Much Processed Meat

“The hacker mystique posits power through anonymity. One does not log on to the system through authorized paths of entry; one sneaks in, dropping through trap doors in the security program, hiding one’s tracks, immune to the audit trails that we put there to make the perceiver part of the data perceived. It is a dream of recovering power and wholeness by seeing wonders and not by being seen.”

—Pam Rosenthal

Flesh Made Data: Part I

This quote, which comes from a chapter in Wendy Hui Kyong Chun’s Control and Freedom on the Orientalization of cyberspace, gestures toward the values embedded in the Internet as a construct. Reading this quote, I found myself wondering about the ways in which identity, users, and the Internet intersect in the present age. Although we certainly witness remnants of the hacker/cyberpunk ethic in movements like Anonymous, it would seem that many Americans exist in a curious tension that exists between the competing impulses for privacy and visibility.

Looking deeper, however, there seems to be an extension of cyberpunk’s ethic, rather than an outright refusal or reversal: if cyberpunk viewed the body as nothing more than a meat sac and something to be shed as one uploaded to the Net, the modern American seems, in some ways, hyper aware of the body’s ability to interface with the cloud in the pursuit of peak efficiency. Perhaps the product of a self-help culture that has incorporated the technology at hand, we are now able to track our calories, sleep patterns, medical records, and moods through wearable devices like Jawbone’s UP but all of this begs the question of whether we are controlling our data or our data is controlling us. Companies like Quantified Self promise to help consumers “know themselves through numbers,” but I am not entirely convinced. Aren’t we just learning to surveil ourselves without understanding the overarching values that guide/manage our gaze?

Returning back to Rosenthal’s quote, there is a rather interesting way in which the hacker ethic has become perverted (in my opinion) as the “dream of recovering power” is no longer about systemic change but self-transformation; one is no longer humbled by the possibilities of the Internet but instead strives to become a transformed wonder visible for all to see.

Flesh Made Data: Part II

A spin-off of, and prequel to, Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009), Caprica (2011-2012) transported viewers to a world filled with futuristic technology, arguably the most prevalent of which was the holoband. Operating on basic notions of virtual reality and presence, the holoband allowed users to, in Matrix parlance, “jack into” an alternate computer-generated space, fittingly labeled by users as “V world.”[1] But despite its prominent place in the vocabulary of the show, the program itself never seemed to be overly concerned with the gadget; instead of spending an inordinate amount of time explaining how the device worked, Caprica chose to explore the effect that it had on society.

Calling forth a tradition steeped in teenage hacker protagonists (or, at the very least, ones that belonged to the “younger” generation), our first exposure to V world—and to the series itself—comes in the form of an introduction to an underground space created by teenagers as an escape from the real world. Featuring graphic sex, violence, and murder, this iteration does not appear to align with traditional notions of a utopia but might represent the manifestation of Caprican teenagers’ desires for a world that is both something and somewhere else. And although immersive virtual environments are not necessarily a new feature in Science Fiction television, with references stretching from Star Trek’s holodeck to Virtuality, Caprica’s real contribution to the field was its choice to foreground the process of V world’s creation and the implications of this construct for the shows inhabitants.

Seen one way, the very foundation of virtual reality and software—programming—is itself the language and act of world creation, with code serving as architecture. If we accept Lawrence Lessig’s maxim that “code is law”, we begin to see that cyberspace, as a construct, is infinitely malleable and the question then becomes not one of “What can we do?” but “What should we do?” In other words, if given the basic tools, what kind of existence will we create and why?

Running with this theme, the show’s overarching plot concerns an attempt to achieve apotheosis through the uploading of physical bodies/selves into the virtual world. I found this series particularly interesting to dwell on because here again we had something that recalls the cyberpunk notion of transcendence through data but, at the same time, the show asked readers to consider why a virtual paradise was more desirous than one constructed in the real world. Put another way, the show forces the question, “To what extent do hacker ethics hold true in the physical world?”

[1] Although the show is generally quite smart about displaying the right kind of content for the medium of television (e.g., flushing out the world through channel surfing, which not only gives viewers glimpses of the world of Caprica but also reinforces the notion that Capricans experience their world through technology), the ability to visualize V world (and the transitions into it) are certainly an element unique to an audio-visual presentation. One of the strengths of the show, I think, is its ability to add layers of information through visuals that do not call attention to themselves. These details, which are not crucial to the story, flush out the world of Caprica in a way that a book could not, for while a book must generally mention items (or at least allude to them) in order to bring them into existence, the show does not have to ever name aspects of the world or actively acknowledge that they exist.

Bouncing Off the Wall

Personalization, as exemplified by the popularity of music services like Pandora, has become a defining characteristic of a 21st century American musical sensibility; with an increasing number of Americans gaining access to on demand content, it would seem that the creation of a contemporary Great American Songbook is not only unlikely but quite possibly unwanted. And yet, despite the growing insularity of listening habits, it would seem that American popular culture continues to present individuals with auditory cultural touchstones in the form of viral singles. For better or for worse, creations like Rebecca Black’s “Friday” have become entities that we organize around, forming taste communities grounded in our reaction to the song.

The importance of music in personal history and the construction of identity became oddly salient recently with the broadcast of HBO’s Phil Spector. It is, I think, all too easy to get caught up in ridiculing the appearance of Phil Spector. A notable recluse in his later years, Spector was thrust into the spotlight while on trial in 2003 for the murder of Lana Clarkson; somewhat given to eccentricity in both lifestyle and presentation, publicized images of Spector lent themselves to commentary that, more often than not, almost necessarily included mention of Spector’s hair.

The importance of music in personal history and the construction of identity became oddly salient recently with the broadcast of HBO’s Phil Spector. It is, I think, all too easy to get caught up in ridiculing the appearance of Phil Spector. A notable recluse in his later years, Spector was thrust into the spotlight while on trial in 2003 for the murder of Lana Clarkson; somewhat given to eccentricity in both lifestyle and presentation, publicized images of Spector lent themselves to commentary that, more often than not, almost necessarily included mention of Spector’s hair.

And although we might criticize the movie for overacting and underdeveloped characters, upon reflection what struck me as particularly poignant about the film was the way in which it reminded me that Phil Spector songs have had a memorable influence in my life.[1]

Using Spector as a jumping off point I began to think this week on the relationship between music, technology, and American social history; although it is tempting to look back and claim that landmark songs “changed” American culture, I instead want to pick up on the idea from this week’s readings that technology and culture (both in the form of music and more broadly) are mutually constitutive processes.

It is, for example, difficult to talk about the impact of Phil Spector’s songs without referencing The Wall of Sound. Born out of a (in retrospect) rather stubborn refusal to embrace stereo sound, Spector engineered a technique wherein sound from the musicians was piped down into echo chambers and then recorded, in effect creating a metaphorical “wall” of sound.

Having not studied music extensively as an academic subject, I find myself still struggling with some questions and concepts. Does the Wall of Sound provide an example of Simon Frith’s (building on Andrew Chester) assertion that Western popular music absorbed Afro-American forms and conventions, producing an “intentionally” complex artifact? As Firth notes, an intentionally complex structure “is that constituted by the parameters of melody, harmony and beat, while the complex is built up by modulation of the basic notes and by inflexion of the basic beat.” (269)

More importantly, however, I wonder how Spector’s technique builds upon conventions that had long been established in African American gospel music and to what extent it was really “new.” Consistent with a larger move in rock music at the time, I marvel at how Phil Spector’s early songs helped to elevate ethnic minorities into the spotlight but also, at the same time, claimed their cultural practices for mainstream America.

Music, History, and Bioshock Infinite

Consistent with Phil Spector, what I am most interested in is the way in which we use fiction to look back on a past that is both imagined and real. How do we make sense of things in retrospect and what does our thought process tell us about the way that we understand the present? Although my thoughts are not fully formed on the subject, I am curious about how pieces of our cultural past are strategically deployed to foreground certain parts of our cultural history while obscuring others.

Bioshock Infinite is a video game premised on a many worlds theory, presenting an alternate history of America in the form of the utopic/dystopic floating city of Columbia. Reflecting sentiments from early 20th century America, the city evidences strong tones of nationalism, theocracy, and jingoism. And, given our continuing struggle with race (see “Accidental Racist”), I wonder about how something like Bioshock Infinite speaks to the way in which we see ourselves in relationship to our own history.

To be sure, the game plays fast and lose with history as it incorporates musical easter eggs throughout the world. “God Only Knows,” a song influenced by Spector’s Wall of Sound technique, makes an appearance early on in the form of a barbershop quartet.

Although rather charming, there is a way in which this type of action reflects a modern sensibility that songs (or perhaps moments in history in general) can be divorced from their surrounding context and transplanted as discrete units. Given the game’s logic I am fully willing to concede that a composer could have peered through dimensions and lifted this song but it seems unlikely that he would know why such a song was popular in the first place. This move seems to be much more about the developers trying to establish a relationship with players than creating a world (which is fine), but the way in which they have gone about it makes me worry that our understanding of cultural artifacts ignores the way in which they are part of systems.

As a parting gift, Bioshock Infinite also features this…

[1] This is, to be sure, an intentional on the part of writer/director David Mamet who even has Phil Spector suggest at one point that his song was playing the first time that his lawyer was felt up.

A Light in the Dark

In his recent post “Where Are Our Bright Science-Fiction Futures?” Graeme McMillan reflects on the dire portraits of the future portended by summer science fiction blockbusters. Here McMillian gestures toward—but does not ultimately articulate—a very specific cultural history that is infused with a sense of nostalgia for the American past.

“There was a stretch of time — from the early 20th century through the beginning of comic books — when science fiction was an exercise in optimism and what is these days referred to as a “can-do” attitude.”

McMillan goes on to write that “such pessimism and fascination with future dystopias really took hold of mainstream sci-fi in the 1970s and ’80s, as pop culture found itself struggling with general disillusionment as a whole.” And McMillan is not wrong here but he is also not grasping the entirety of the situation

To be sure, the fallout the followed the idealistic futures set forth by 60s counterculture—again we must be careful to limit the scope of our discussion to America here even as we recognize that this reading only captures the broadest strokes of the genre—may have had something to do with the rise in “pessimism” but I would also contend that the time period that McMillan refers to was also one that had civil unrest pushed to the forefront of its consciousness. More than a response to hippie culture was a country that was struggling to redefine itself in the midst of an ongoing series of projects that aimed to secure rights for previously disenfranchised groups. McMillan’s nod toward disillusionment is important to bear in mind (as is a growing sense of cynicism in America), but the way in which that affective stance impacts science fiction is much more complex than McMillan suggests.

McMillan needs to, for example, consider the resurgence of fairy tales and folklore in American visual entertainment that has taken on an increasingly “dark” tone; from Batman to Snow White we see a rejection of the unfettered good. Fantasy, science fiction, and horror are all cousins and we see the explorations of our alternate futures playing out across all three genres.

In light of this it only makes sense that the utopic post-need vision of Star Trek would find no footing; American culture was actively railing against hegemonic visions of the present and so those who were in the business of speculating about possible futures began to consider the implications of this process, particularly with respect to race and gender.

Near the end of his piece McMillan opines:

That’s the edge that downbeat science fiction has over the more hopeful alternative. It’s easier to imagine a world where things go wrong, rather than right, and to believe in a future where we manage to screw it all up.

Here, McMillian demonstrates a fundamental failure to interrogate what science/speculative fiction does for us in the first place before proceeding to consider how its function is related to its tone. I would stridently argue that this binary about hopeful/pessimistic thinking is misguided for a number of reasons.

First, it is evident that McMillan is conflating the utopic/dystopic dimension with hopeful/pessimistic. While we might generally make a case that the concept of utopia feels more hopeful on the surface this is not necessarily the case; instead, I would argue that utopia feels more comforting, which is not necessarily the same thing as hopeful. To illustrate the point, we need only consider the recent trend in YA dystopic fiction which, on its surface, contains an explicit element of critique but is often somewhat hopeful about the ability of its protagonists to overcome adversity. Earlier in his piece McMillan refers to this type of scenario as a “semiwin” but I would argue that it is, for many authors and readers, a complete win, albeit one that focuses generally on humans and individualism.

The other point that McMillan likely understands but did not address is that writing about situations in which everything “goes right” is not actually all that interesting. In his invocation of the science fiction of the early 20th century McMillan fails to recognize the way in which that particular strain of science fiction was the result of a very specific inheritor of the notion of scientific progress (and the future) that dates back to the Enlightenment but was largely spurred on by the 1893 World’s Fair. Additionally, although it is somewhat of a cliché, we must consider the way in which the aftermath of the atomic bomb (and the resulting fear of the Cold War) shattered our understanding that technology and science would lead to a bright new world.

Moreover, the fiction that McMillan cites was rather exclusive to white middle class amateur males (often youth) and the “hope” represented in those fictions was largely possible because of a shared vision of the future in this community. Returning to a discussion of the 70s and 80s we see that such an idyllic scenario is really no longer possible as we understand that utopias are inherently flawed for they can only ever represent a singular idea of perfection. Put another way, one person’s utopia is another person’s subjugation.

I would also argue that it is, in fact, easier to imagine a future where everything is right because all one has to do to engage in this project is to “fix” the things that are issues in the current day and age. This is easy. The difficult task is to not only craft a compelling alternate future but to consider how we get there and this is where the “pessimistic” fiction’s inherent critique is often helpful. Fiction that is, on its surface, labeled as “pessimistic” (which is really a simplified reading when you get down to it) actually has the harder task of locating the root cause of an issue and trying to understand how the issue is perpetuated or propagated. Although it might seem paradoxical, “pessimistic” is actually hopeful because it argues that things can change and therefore there is a way out.

Alternatively, we might consider how the language of the apocalypse is linked to that of nature. On one axis we have the adoption of the apocalyptic in reference to climate change and, on a related dimension, we are beginning to see changes in the post-apocalyptic worlds that suggest the resurgence of nature as opposed to the decimation of it. McMillan laments that we should “try harder” if we can’t imagine a world that we have not ruined but I would counter this to suggest that many Americans are intimately aware, on some level, that humans have irrevocably damaged the world and so our visions of the future continue to carry this burden.

Science Fiction as a genre is much more robust than McMillan gives it credit for and, ultimately, I would suggest that he try harder to really understand how the genre is continually articulating multiple visions of the future that are complex and potentially contradictory. The simplification of these stories that takes place for a movie might strip them down into palatable themes and McMillan needs to speak to the ways in which his evidence is born out of an industry whose values most likely have an effect on the types of fictions that make it onto the screen.

The Brass Age (Redux?)

What else is speculative fiction other than a bagful of nickels?

This image, from Dexter Palmer’s book, has long haunted me since I first encountered it. Hope, possibility, dreams unrealized—the nickels manifest an interesting relationship between Harold and technology that extended far beyond the original creator’s intention. And, in a way, isn’t this what steampunk and science fiction are all about? It is what is represented by the nickels rather than the nickels themselves that are important and we might even turn to Saussure’s semiotic labels of objects, signified, sign as we realize that there also exists a tension because the only way to manifest the dreams is to spend the nickel—what is the balance between dreams realized and the pull of dreams left to dream?

This image, from Dexter Palmer’s book, has long haunted me since I first encountered it. Hope, possibility, dreams unrealized—the nickels manifest an interesting relationship between Harold and technology that extended far beyond the original creator’s intention. And, in a way, isn’t this what steampunk and science fiction are all about? It is what is represented by the nickels rather than the nickels themselves that are important and we might even turn to Saussure’s semiotic labels of objects, signified, sign as we realize that there also exists a tension because the only way to manifest the dreams is to spend the nickel—what is the balance between dreams realized and the pull of dreams left to dream?

Ultimately, however, we must also ask ourselves just how “punk” is steampunk? If the term endeavors to draw upon the Western history of punks from the 1970s, it must then speak to a form of subversion or resistance against the dominant culture of the time. Although one might argue that the aesthetic of steampunk along with an emphasis on construction or reappropriation of machines certainly represents a challenge to the status quo, the centrality of technology in the lives of steampunks certainly seems to remain aligned with current views. Technology looks different, but does it function in a fundamentally different way?

Although a casual fan of the culture, I also continue to wonder about just how deep this love of Victorian-era ideals go. Perhaps I am just sensitized to the resurgence of Gothic (e.g., horror, gothic Lolita, etc.) and Victorian because of my research interests? I find myself struggling with the grand visions put forth in steampunk (not unlike other forms of technological utopia we have encountered previously in the course) as erasing the very real struggles that surrounded the appearance of steam-powered technology in the 19th century. In addition to the pollution and physical hazards mentioned in Rebecca Onion’s piece, I also think about how the new machine culture affected workers’ health. But even beyond the scope of the machine and the factory, steampunk seems to pluck out fetishized elements of clockwork while leaving the very real (at the time) menaces of disease, improper sanitation, and corpse stealing that were intertwined with developing technology in the Victorian age.

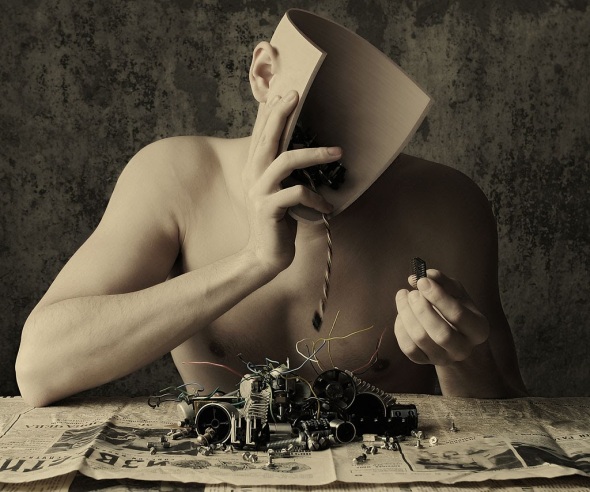

But then again, perhaps I am reading this all wrong. Does steampunk speak to a deep cultural need for us to strip away the layers of shine and sheen that surround modern implementations of technology? To see the gears and pistons is to see behind the curtain and experience a different type of technological wonder all together. Is there a sort of excitement that comes from knowing that gadgets might not work? And, as mentioned earlier, surely the culture of production that pervades the experience of being steampunk speaks to an increasingly diminished notion of the average person as tinkerer.

But then again, perhaps I am reading this all wrong. Does steampunk speak to a deep cultural need for us to strip away the layers of shine and sheen that surround modern implementations of technology? To see the gears and pistons is to see behind the curtain and experience a different type of technological wonder all together. Is there a sort of excitement that comes from knowing that gadgets might not work? And, as mentioned earlier, surely the culture of production that pervades the experience of being steampunk speaks to an increasingly diminished notion of the average person as tinkerer.

Black (and Brown) to the Future

In retrospect, it should have been obvious.

Growing up in Hawaii, I learned about westward expansion, the Trail of Tears, and Manifest Destiny in US history courses but was never asked to connect the events presented by my textbooks to the world around me. I was certainly aware of sovereignty movements—I’d even taken the mandatory tour that talked about the imprisonment of Hawaii’s last queen!—but never took time to understand the issue because, to me, it wasn’t my problem.

Or, worse, as a child attending a school founded by missionaries, I had internalized the ethos of Western colonization and domination. What else could I do but shrug, for that’s what Whites/Americans (and conflating those two is a whole separate host of issues) did?

So maybe this whole history combined with early space exploration in Science Fiction to convince me that colonization was something to be done in the name of progress. Although some sense of this must have floated in the background, I never questioned whose dreams had to die so that my reality was secure; history, after all, is written by the winners.

Needless to say, deconstructing this is difficult for me.

To make matters worse, I often wonder how colonialist tendencies have, like many subversive acts, become increasingly harder to see as fewer gross examples of physical imperialism appear. Instead of marching in with an army, states employ ideology in an attempt to legitimate their positions of privilege; by setting the “first-world” standard as the norm, powers like the United States strive to conquer through images, not physical occupation.

Although certainly not unique to Science Fiction, I often wonder about figures who purport to have a close relationship to the Truth: whether seeing it, speaking it, hearing it, or feeling it, there often seems to be an underlying message that one (and only one!) form of objective truth exists in these fictional worlds. In this context, words like “liberation” or “revelation” become potentially problematic as individuals profess an obligation to set people on the “right path.” In this process, false gods must be unmasked, natives need the help of mainstreamed humans, and the “primitive” treatment of women in “barbaric” cultures must be addressed. In short, wars are less about skirmishes over geography and territory in the traditional sense than they are about ideological contests.

If we accept that these represent strains of colonialist themes in the genre, then the fiction of post-colonial SF seems to present two challenges: introducing the voices of those subject to colonialist tendencies—turning them from subjects of imperial empires to anthropological subjects full of agency—and questioning the ways in which colonialist thought has been institutionalized, coded, and made systemic.

Points for Trying?

The obvious answer is that if early Science Fiction was about exploring outer space, the writings of the late 20th century were largely about exploring inner space. More than just adventure tales filled with sensation or exploration (or cyberpunk thrill) the offerings that I encountered also spoke to, in a way, the colonizing of emotion. Thinking about Science Fiction in the late 20th century and early 21st century, I wondered how some works spoke to our desire for a new form of exploration. We seek to reclaim a sense of that which is lost, for we are explorers, yes—a new form of adventurer who seeks out the raw feeling that has been largely absent from our lives. Jaded, we long to be moved; jaded, we have set the bar so high for emotion that the spectacular has become nothing more than a nighttime attraction at Disneyworld.

At our most cynical, it would be easy to blame Disney for forcing us to experience wonder in scripted terms with false emotion constructed through tricks of architectural scale and smells only achievable through chemical slight of hand. But “force” seems like the wrong word, for doesn’t a part of us—perhaps a part that we didn’t even know that we had—want all of this? We crave a Main Street that most of us have never (and will never) know because it, in some fashion, speaks to the deeply ingrained notion of what it means to be an American who has lived in the 20th and 21st centuries.

For me, there are glaring overlaps with this practice and emotional branding, but what keeps me up at night is looking at how this process may have infiltrated education through gamification.

Over the past few years, after reading thousands of applications for the USC Office of Undergraduate Admission, I began to wonder how the college application structures students’ activities and identities. On one hand, I heard admission colleagues complaining about how they just wanted applicants to exhibit a sense of passion and authenticity; on the other, I saw students stressing out over their applications and their resumes. The things that I was seeing were impressive and students seemed to devote large amounts of time to things, but I often wondered, “Are they having any fun?”

Were students just getting sucked into a culture that put a premium on achievement and not really stopping to think about what they were doing or why? We can talk about the positive aspects of gamification, levling and badges, but as the years wore on, I really began to see titles on activity summaries as things that were fetishized, obsessed over, and coveted. Students had learned the wrong lesson—not to suggest in the slightest that they are primarily or solely responsible for this movement—going from a race to accumulate experience to merely aggregating the appearance of having done so. How could I convince them that, as an admission officer, it was never really about the experience in the first place but instead how a particular activity provided an opportunity for growth. It was—and is—about the process and not the product.

But, that being said, I try not to fault students for the very actions that frustrated me as a reader are reinforced daily in all aspects of education (and life in general). Processes are messy, vague, and fluid while products are not. How would one even go about conceiving a badge for emotional maturity? Would one even want to try?

Perhaps I am clinging to notions of experience that will become outdated in the future. Science Fiction challenges us to consider worlds where experiences and memory can be saved, uploaded, and imprinted and, really, what are recreational drugs other than our clumsy attempt to achieve altered experiences through physiological change? I don’t know what the future will bring, but I do know that my former colleagues in admission are likely not thinking about the coming changes and will struggle to recalibrate their metrics as we move forward.

Eat My Dust: Uncovering who is left behind in the forward thinking of Transhumanism

It should come as no surprise that the futurist perspective of transhumanism is closely linked with Science Fiction given that both areas tend to, in various ways, focus on the intersection of technology and society. Generally concerned with the ways in which technology will serve to enhance human beings (along the way possibly evolving past “human” to become “posthuman”), the transhumanist movement generally adopts a positivist stance as it envisions a future in which disease and aging are eradicated or cognitive processes accelerated. [1] In one way, transhumanism is presented as a cure-all for the problems that have plagued human beings throughout our history, providing hope that our fragile, corruptible, mortal, and impermeable bodies can forever be augmented, maintained, fixed, or reconstituted. A seductive promise, surely. Science Fiction then takes the ideas presented by transhumanist theory and makes them a little more tangible, affording us the opportunity to visit these futurist communities as we dream about how our destiny will be changed for the better while also allowing us to glimpse warnings against hubris through works like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Without giving it much thought, it seems as though we are readily able to spot the presence of transhumanism in Science Fiction—but what if we were to reverse the gaze and instead use Science Fiction as a critical lens through which transhumanism could be viewed and understood? In short, what are lessons that we can garner from a close reading of Science Fiction texts can be used as tools to think through both the potential benefits and drawbacks of this particular direction for humanity?

Although admittedly an oversimplification, the utopia/dystopia binary gives us a place to start. Lest we become overly enamored with the potential and the promise of a movement like transhumanism, we must remember to ask ourselves, “Just whose utopia is it?”[2] Using Science Fiction as framework to understand the transhumanist movement, we are wary of a body of work that has traditionally excluded minority perspectives (e.g., the female gender or race) until called to explicitly express such views (see the presence of, and need for, works labeled as “feminist Science Fiction”). This is, of course, not to suggest that exceptions to this statement do not exist. However, it seems prudent here to mention that although the current landscape of Science Fiction has been affected by the democratizing power of the Internet, its genesis was largely influenced by an author-audience relationship that drew on experiences and knowledge primarily codified in White middle-class males. Although we can readily derive examples of active exclusion on the part of the genre’s actors (i.e., we must remember that this is not a property of the genre itself), we must also recognize a cultural context that steered various types of minorities away from fiction grounded in science and technology; for individuals who did not grow up idolizing the lone boy inventor/tinkerer or fantasizing about the space race, Science Fiction of the early- to mid-20th century did not readily represent reality of any sort, alternate, speculative, future, or otherwise.

If we accept that many of the same cultural factors that worked against diversity in early forms of Science Fiction continue to persist today with respect to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (Johnson, 1987; Catsambis, 1995; Nosek, et al., 2009) we must also question the vision put forth by transhumanists and be willing to accept that, for all its glory, the movement may very well represent an incomplete ideal state—invariably all utopias need revision. Although we might consider our modern selves as more progressive than authors of early Science Fiction, examination of current discourse surrounding transhumanism reveals a continued failure to incorporate discussions surrounding race (Ikemoto, 2005). In particular, this practice is potentially problematic as the Biomedical/Health field (in which transhumanism is firmly situated) has a demonstrated history of legitimizing multiple types of discrimination based on dimensions that include, but certainly are not limited to, race and gender. By not attempting to understand the implications of the movement from the viewpoint of multiple stakeholders, transhumanism potentially becomes a site for dominant ideology to reinforce its sociocultural constructions of the biological body. Moreover, if we have learned anything from the ways in which new media use intersects with race and socioeconomic status, we must be wary of the ways in which technology/media can exacerbate existing inequalities (or create new ones!). The issue of accesses to the technology of transhumanism immediately becomes pertinent as we see the potential for the restratification of society according to who can afford (broadly defined, including not just to cost but also including things like missed work due to recovery time) to have these procedures performed. In short, much like in Science Fiction, we must not only question who the vision is authored by, but also who it is intended for. Yet, far from suggesting that current transhumanist aspirations are necessarily or inherently incompatible with other strains, I merely argue that many types of voices must be included in the conversation if we are to have any hope of maintaining a sense of human dignity.

If we accept that many of the same cultural factors that worked against diversity in early forms of Science Fiction continue to persist today with respect to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (Johnson, 1987; Catsambis, 1995; Nosek, et al., 2009) we must also question the vision put forth by transhumanists and be willing to accept that, for all its glory, the movement may very well represent an incomplete ideal state—invariably all utopias need revision. Although we might consider our modern selves as more progressive than authors of early Science Fiction, examination of current discourse surrounding transhumanism reveals a continued failure to incorporate discussions surrounding race (Ikemoto, 2005). In particular, this practice is potentially problematic as the Biomedical/Health field (in which transhumanism is firmly situated) has a demonstrated history of legitimizing multiple types of discrimination based on dimensions that include, but certainly are not limited to, race and gender. By not attempting to understand the implications of the movement from the viewpoint of multiple stakeholders, transhumanism potentially becomes a site for dominant ideology to reinforce its sociocultural constructions of the biological body. Moreover, if we have learned anything from the ways in which new media use intersects with race and socioeconomic status, we must be wary of the ways in which technology/media can exacerbate existing inequalities (or create new ones!). The issue of accesses to the technology of transhumanism immediately becomes pertinent as we see the potential for the restratification of society according to who can afford (broadly defined, including not just to cost but also including things like missed work due to recovery time) to have these procedures performed. In short, much like in Science Fiction, we must not only question who the vision is authored by, but also who it is intended for. Yet, far from suggesting that current transhumanist aspirations are necessarily or inherently incompatible with other strains, I merely argue that many types of voices must be included in the conversation if we are to have any hope of maintaining a sense of human dignity.

And dignity[3] plays an incredibly important role in bioethical discussions as we being to take a larger view of transhumanism’s potential effect, folding issues of disability into the discussion as we contemplate another (perhaps more salient) way in which society can act to inscribe form onto a body. Additionally, mention of disability forces an expansion in the definition of transhumanism beyond mere “enhancement,” with its connotation of augmentation of able-bodied individuals, to include notions of treatment. Although beyond the scope of this paper, the treatment/enhancement distinction is worth investigating as it not only has the potential to designate and define concepts of normal functioning (Daniels, 2000) but also suffers from a general lack of consensus regarding use of the terms “treatment” and “enhancement” (Menuz, Hurlimann, & Godard, 2011). But, looking at the overlap of treatment, enhancement, and disability, we must ask ourselves questions like, “If one of the potential benefits of transhumanism is the prevention and/or rectification of conditions like disability and deformity, who should be fixed? Who deserves to be fixed? But, most importantly, who needs to be fixed?”

Continuing to apply perspectives used to analyze the intersection of race, class, and technology, we see the potential for transhumanism thought to impose a particular kind of label onto individual bodies, inscribing a particular system of values in the process. Take, for example, Sharon Duchesneau and Candy McCullough who have been criticized for actively attempting to conceive a deaf child (Spriggs, 2002). Although the couple (both of whom are deaf) do not consider deafness to be a disability or a liability, a prevailing view in America works to force a particular type of identity onto the couple and their child (i.e., deafness is abnormal) and the family will undoubtedly be forced to eventually confront thinking informed by transhumanism in justifying their choice and very existence.

However, even seemingly straightforward cases like Olympic hopeful Oscar Pistorius have forced us to grapple with new questions regarding the consideration of recipients of biomedical augmentation. Born without fibula, a state that would likely be classified as “disabled” by himself and others, Oscar Pistorius won gold medals in the 100, 200, and 400 meter events at the 2008 Paraolympic Games but was initially banned from entering the Olympic Games due to concern that his artificial legs conferred an unfair advantage. Although this ruling was later overturned, Pistorius failed to make the qualifying time to participate in the 2008 Olympics Games. Pistorius has, however, met the qualifying standard for the 2012 Games and his participation will assuredly affect future policy regarding the use of artificial limbs as well as a renegotiation of the term “disabled” (Burkett, McNamee, & Potthast, 2011; Van Hilvoorde & Landeweerd, 2010). Interestingly, Pistorius also raises larger issues about the nature of augmentation in Sport, an area that has long wrestled with the concept of competitive advantages conferred through body modification and enhancement.

However, even seemingly straightforward cases like Olympic hopeful Oscar Pistorius have forced us to grapple with new questions regarding the consideration of recipients of biomedical augmentation. Born without fibula, a state that would likely be classified as “disabled” by himself and others, Oscar Pistorius won gold medals in the 100, 200, and 400 meter events at the 2008 Paraolympic Games but was initially banned from entering the Olympic Games due to concern that his artificial legs conferred an unfair advantage. Although this ruling was later overturned, Pistorius failed to make the qualifying time to participate in the 2008 Olympics Games. Pistorius has, however, met the qualifying standard for the 2012 Games and his participation will assuredly affect future policy regarding the use of artificial limbs as well as a renegotiation of the term “disabled” (Burkett, McNamee, & Potthast, 2011; Van Hilvoorde & Landeweerd, 2010). Interestingly, Pistorius also raises larger issues about the nature of augmentation in Sport, an area that has long wrestled with the concept of competitive advantages conferred through body modification and enhancement.

Ultimately we see that while improvements in human-computer interfaces, computer-mediated communication, neuroscience, and biomechanics paint a resplendent future full of possibilities for a movement like transhumanism, the philosophy also reveals a struggle over phrases like “human enhancement” that have yet to be resolved. Although I am personally most interested in issues of identity and religion that will most likely arise as a result of this cultural transformation (see Spezio, 2005), I want to suggest that larger societal issues must also be raised and discussed. Although we might understand the fundamental issue of transhumanism as a question of whether we should accept the body the way it is, I think the more instructive line of inquiry (if perhaps harder to initially understand) thoroughly examines the ways in which transhumanism builds upon a historical construction of the concept of the body as natural while simultaneously challenging it. Without such critical reflection, transhumanism, like many utopic endeavors, runs the risk of limiting our future to one that is restricted by the types of issues that we can imagine in the present; although our path forward is necessarily guided by the questions that we ask today, utopia turns to dystopia when we fixate on a idealized state and forget why we even bothered to seek advancement in the first place. If, however, we apply the theoretical frameworks provided by Science Fiction to our real lives and reconceptualize utopia as a process—a pursuit that is ongoing, reflexive, and dynamic—instead of as a product, we stand a chance of accomplishing what we sought to do without diminishing individual autonomy or being consumed by the very technology we hoped to integrate.

[1] Interestingly, in some conceptualizations, aging is now being understood as a disease-like process rather than a biological inevitability. Aside from the radical shift in thinking represented by a movement away from death as biological fact, I am fascinated by the ways in which this indicates a changing understanding of the “natural” state of our bodies.

[2] This should not suggest that a utopia/dystopia binary is the only way of considering this issue, but merely one way of utilizing language central to Science Fiction in order to understand transhumanism. Moreover, like most things, transhumanism is multidimensional and I am hesitant to cast it onto a good/bad dichotomy but I think that the notion of critical utopia can be instructive here.

[3] A complex notion itself worthy of detailed discussion. A recent issue of The American Journal of Bioethics featured a number of articles on the concept of dignity and how transhumanism worked to uphold or undermine it. See de Melo-Martin, 2010; Bostram, 2008; Sadler, 2010; Jotterand, 2010. Although “dignity” seems difficult to define concretely, Menuz, Hurlimann, and Godard suggest a “personal optimum state” based on cultural, socio-historical, biological, and psychological features (2011). One might note, however, that the highly indivdualized nature of Menuz, Hurlimann, and Godard’s criteria makes implimentation of policy difficult.

Works Cited

Bostram, N. (2008). Dignity and Enhancement. In A. Schulman (Ed.), Human Dignity and Bioethics: Essays Commissioned by the President’s Council on Bioethics (pp. 173-207). Washington, DC: The President’s Council on Bioethics.

Burkett, B., McNamee, M., & Potthast, W. (2011). Shifting Boundaries in Sports Technology and Disability: Equal Rights or Unfair Advantage in the Case of Oscar Pistorius? Disability and Society, 26(5), 643-654.

Catsambis, S. (1995). Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Science Education in the Middle Grades. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 32(3), 243-257.

Daniels, N. (2000). Normal Functioning and the Treatment-Enhancement Distinction. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 9, 309-322.

de Melo-Martin, I. (2010). Human Dignity, Transhuman Dignity, and All That Jazz. The American Journal of Bioethics, 10(7), 53-55.

Ikemoto, L. (2005). Race to Health: Racialized Discourses in a Transhuman World. DePaul Journal of Health Care Law, 9(2), 1101-1130.

Johnson, S. (1987). Gender Differences in Science: Parallels in Interest, Experience and Performance. International Journal of Science Education, 9(4), 467-481.

Jotterand, F. (2010). Human Dignity and Transhumanism: Do Anthro-Technological Devices Have Moral Status? The American Journal of Bioethics, 10(7), 45-52.

Menuz, V., Hurlimann, T., & Godard, B. (2011). Is Human Enhancement Also a Personal Matter? Science and Engineering Ethics.

Nosek, B. A., Smyth, F. L., Sriram, N., Lindner, N. M., Devos, T., Ayala, A., et al. (2009, June 30). National Differences in Gender: Science Stereotypes Predict National Sex Differences in Science and Math Achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(26), 10593–10597.

Sadler, J. Z. (2010). Dignity, Arete, and Hubris in the Transhumanist Debate. American Journal of Bioethics, 10(7), 67-68.

Spezio, M. L. (2005). Brain and Machine: Minding the Transhuman Future. Dialog: A Journal of Theology, 44(4), 375-380.

Spriggs, M. (2002). Lesbian Couple Create a Child Who Is Deaf Like Them. Journal of Medical Ethics, 283.

Van Hilvoorde, I., & Landeweerd, L. (2010). Enhancing Disabilities: Transhumanism under the Veil of Inclusion? Disability and Rehabilitation, 32(26), 2222-2227.

I Gotta Watch My Body–I’m Not Just Anybody

Although I admittedly worked backward from The Matrix, slowly discovering Blade Runner and Snow Crash as I delved deeper into Science Fiction. In retrospect, I realize that the genre of Science Fiction is much broader than the theme of cyberpunk, but, as a child growing up in the 90s, the mainstream Science Fiction that I encountered seemed to belong to this subgenre. I suspect that I, like many others, was drawn in by the aesthetic more than the content per se (I was not heavily into technobabble much less willing to identify in any way as a computer geek), but I also wonder if the genre spoke to me on another level as well.

Going back over the works now, I find myself struck by the concept of embodiment present throughout much of the fiction. Incorporating the creation of computer technologies like the Internet and virtual reality into their work, many authors seemed to speculate on the eventual cultural impacts on the traditional mind/body duality as technological societies progressed into the future (e.g., Don Riggs’ “disembodied” and “trans-embodied”). Looking over the works of cyberpunk, there seem to be many interesting thought experiments regarding the nature of the body, what constituted it, and how our brain worked with/against our bodies. The question that I am left with is: What happened to all of that discussion?

Although I have not done an extensive study of modern Science Fiction, it seems like much of the issue appears to be settled. In recent memory, Surrogates comes to mind as an example of body swapping (albeit between live and mechanical bodies) but doesn’t seem to explore the impact of bodies’ interactions with the world around them and how this sensation also serves to constitute the construction of the body (i.e., the body is not merely bounded by skin). The logic of the movie seems to indicate that one can readily swap bodies (with a slight sense of disorientation as one moves from one body to the next) but never really addresses the issue that it is entirely possible that these bodies exist in two slightly different worlds because they react to their environments in different ways.

Although I have not done an extensive study of modern Science Fiction, it seems like much of the issue appears to be settled. In recent memory, Surrogates comes to mind as an example of body swapping (albeit between live and mechanical bodies) but doesn’t seem to explore the impact of bodies’ interactions with the world around them and how this sensation also serves to constitute the construction of the body (i.e., the body is not merely bounded by skin). The logic of the movie seems to indicate that one can readily swap bodies (with a slight sense of disorientation as one moves from one body to the next) but never really addresses the issue that it is entirely possible that these bodies exist in two slightly different worlds because they react to their environments in different ways.

I struggle with this because I wonder if we have, in a way, given up on our bodies as things that are fallible and subject to decay. We feel betrayed by our bodies when auto-immune diseases manifest and are all too aware that our bodies will wither with age (if we don’t get cancer first). For me, the major impulse in Cyberpunk seemed to be a desire to figure out a way to upload one’s mind to a distributed network, becoming one with the machine in consciousness, if not in body. And yet, in recent years, the focus seems to have swung toward the other end of the continuum (if one can indeed place such things on a linear scale) as we seek to incorporate increasingly advanced biomechanical parts in our bodies. Despite the flourishing of artificial limbs and synthetic organs, we seem to have ceased discussion on what this means for how we conceptualize and define a body. Perhaps the quiet has resulted from our culture coming to a conclusion about how the body is constituted? I think, however, that we have, in a fashion, forgotten about our bodies and how they are not merely containers for our brains. Rather, they are part of a system, with our minds accruing knowledge by virtue of experiencing things through the filter of our body as our bodies, in turn, provide a way for our minds to interact with the physical world around us.

I Want to Break Free

It seems only fitting that Queen’s “I Want to Break Free” begins with a domestic scene that features a housewife vacuuming, for perhaps no time in recent history has been as evocative as the mid-20th century matriarch.[1] Arguably trading potential for security, women were indeed presented with “overchoice” as hundreds of new products became available for consumers—but although the sheer number of choices available increased, one might also argue that the meaningful choices that a woman could make also decreased as society restructured itself in the years following World War II. Science fiction offerings by authors like Pamela Zoline and James Tiptree, Jr. point to various roles for women in America at the time, illuminating the narrow ways in which women could insert themselves into a world that was not their own. Moreover, the path highlighted society lay fraught with ennui, boredom, monotony, and despair—so much so, in fact, that Pamela Zoline’s Sarah Boyle attempts to disrupt her routine and, in so doing, bring about the heat death of the universe (and the end of her suffering).

It seems only fitting that Queen’s “I Want to Break Free” begins with a domestic scene that features a housewife vacuuming, for perhaps no time in recent history has been as evocative as the mid-20th century matriarch.[1] Arguably trading potential for security, women were indeed presented with “overchoice” as hundreds of new products became available for consumers—but although the sheer number of choices available increased, one might also argue that the meaningful choices that a woman could make also decreased as society restructured itself in the years following World War II. Science fiction offerings by authors like Pamela Zoline and James Tiptree, Jr. point to various roles for women in America at the time, illuminating the narrow ways in which women could insert themselves into a world that was not their own. Moreover, the path highlighted society lay fraught with ennui, boredom, monotony, and despair—so much so, in fact, that Pamela Zoline’s Sarah Boyle attempts to disrupt her routine and, in so doing, bring about the heat death of the universe (and the end of her suffering).

Fast forward fifty years and we again see another batch of Desperate Housewives, who suffer from some of the same emotions as their 50s counterparts. Restless and losing a sense of self, the women on Marc Cherry’s drama attempt to illustrate that even well-to-do mothers living in gated communities still struggle to have it all.

And, in many ways, Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror have dealt with the same issues throughout the years, with witches in the 60s like Samantha Stevens (Bewitched) going through the same sorts of domestic trials as the modern Halliwell sisters (Charmed). Important in both of these shows is the presence of the accepting/tolerant (White) male who, although occasionally lacking in comprehension of women or their magic, is certainly understanding. In the case of Bewitched, we see a male who puts up with his wife’s misdeeds and tolerates the existence of magic even as he discourages its use.

Additionally, we see women in these shows often struggling with the expectations of motherhood, which raises notions about feminine identity, female bodies, and reproduction. Explored by Octavia Butler, we are introduced to the theme of male pregnancy, which often results in disastrous consequences for men.[2] Men’s bodies, it seems, cannot handle the task of birth as they are often destroyed in the process of labor.

Additionally, we see women in these shows often struggling with the expectations of motherhood, which raises notions about feminine identity, female bodies, and reproduction. Explored by Octavia Butler, we are introduced to the theme of male pregnancy, which often results in disastrous consequences for men.[2] Men’s bodies, it seems, cannot handle the task of birth as they are often destroyed in the process of labor.

Although uncomfortable, I believe that these types of fiction allow our culture to wrestle with pertinent questions about our relationships to our bodies. Although some scenarios seem impossible (at present, for example, biological males are unable to give birth to offspring), the idea that technology might eventually intervene and allow men to carry to babies to term does not seem to be out of the question. Should such a day come, we can refer back to fiction like that of Octavia Butler in order to better articulate our views on reproduction and sex as we come to see that what we have long considered “natural” is, in fact, merely socially constructed.

Legends of the Fall

When reading the fiction of Cordwainer Smith, I found myself making connections to Richard Matheson‘s I Am Legend. Although I would classify I Am Legend as more of a horror story than a work of Science Fiction—that being said, the genres have a tendency to overlap and a strict distinction, for this current article, is not necessary—both pieces were published in the 1950s, a time assuredly rife with psychological stress. Although we certainly witness an environment coming to terms with the potential impact of mass media and advertising (see discussion from last week’s class), I also associate the time period with the incredible mental reorganization that resulted for many due to the increased migration to the suburbs—a move that would cause many to grapple with issues of competition, conformity, routine, and paranoia. In a way, just as 1950s society feared, the threat did really come from within.

When reading the fiction of Cordwainer Smith, I found myself making connections to Richard Matheson‘s I Am Legend. Although I would classify I Am Legend as more of a horror story than a work of Science Fiction—that being said, the genres have a tendency to overlap and a strict distinction, for this current article, is not necessary—both pieces were published in the 1950s, a time assuredly rife with psychological stress. Although we certainly witness an environment coming to terms with the potential impact of mass media and advertising (see discussion from last week’s class), I also associate the time period with the incredible mental reorganization that resulted for many due to the increased migration to the suburbs—a move that would cause many to grapple with issues of competition, conformity, routine, and paranoia. In a way, just as 1950s society feared, the threat did really come from within.

And “within,” in this case, did not just mean that one’s former neighbors could, one day, wake up and want to eat you (one of the underlying themes in zombie apocalypse films set in suburbia) but also that one’s mental state was subject to bouts of dissatisfaction, depression, and isolation. Neville (the last human in Matheson’s book, who must fight off waves of vampires) and each of the protagonists in Smith’s stories is othered in their own ways and although Smith overtly points to themes of empowerment/disenfranchisement, I could not help but wonder about the psychological stress that each character endured as a result of a sense of isolation. Martel (“Scanners Live in Vain“) fights to retain his humanity (and connection to it) through his wife and cranching, Elaine (“The Dead Lady of Clown Town“) falls in love with the Hunter and fuses with D’joan while Lord Jestocost (“The Ballad of Lost C’mell“) falls in love with an ideal, and finally Mercer (“A Planet Named Shayol“) unwittingly chooses community over isolation by refusing to give up his personality and eyesight.

Throughout the stories of Matheson and Smith, we see that the end result of warfare is a shift in (or acceptance of) a new form of ideology. (This makes sense particularly if we take Smith’s position from Psychological Warfare that “Freedom cannot be accorded to persons outside the ideological pale,” indicating that there will necessarily be winners and losers in the battle necessitated by differences in ideology.) In particular, however, I found “Scanners Live in Vain” and “The Dead Lady of Clown Town” most interesting in that their conclusions point to the mythologizing of characters (Parizianski and Elaine), which is the same sort of realization had by Matheson’s Neville as he comes to terms with the concept that although he was, in his own story, the protagonist, he will be remembered as a conquered antagonist of new humanity. Neville, like Parizianski and Elaine, has become legend.

Throughout the stories of Matheson and Smith, we see that the end result of warfare is a shift in (or acceptance of) a new form of ideology. (This makes sense particularly if we take Smith’s position from Psychological Warfare that “Freedom cannot be accorded to persons outside the ideological pale,” indicating that there will necessarily be winners and losers in the battle necessitated by differences in ideology.) In particular, however, I found “Scanners Live in Vain” and “The Dead Lady of Clown Town” most interesting in that their conclusions point to the mythologizing of characters (Parizianski and Elaine), which is the same sort of realization had by Matheson’s Neville as he comes to terms with the concept that although he was, in his own story, the protagonist, he will be remembered as a conquered antagonist of new humanity. Neville, like Parizianski and Elaine, has become legend.

Ultimately, I think that Smith’s stories weave together a number of interrelated questions: “What is the role of things that have become obsolete?” “What defines a human (or humanity)?” “How is psychological warfare something that is not just done to us by other, but by ourselves?” and, finally, “If psychological warfare is an act that is committed to replace and eradicate ‘faulty’ ideology, what is our role in crafting a new system of values and myths. What does it mean that we become legends?”

The Real-Life Implications of Virtual Selves

“The end is nigh!”—the plethora of words, phrases, and warnings associated with the impending apocalypse has saturated American culture to the point of being jaded, as picketing figures bearing signs have become a fixture of political cartoons and echoes of the Book of Revelation appear in popular media like Legion and the short-lived television series Revelations. On a secular level, we grapple with the notion that our existence is a fragile one at best, with doom portended by natural disasters (e.g, Floodland and The Day after Tomorrow), rogue asteroids (e.g., Life as We Knew It and Armageddon), nuclear fallout (e.g., Z for Zachariah and The Terminator), biological malfunction (e.g., The Chrysalids and Children of Men) and the increasingly-visible zombie apocalypse (e.g., Rot and Ruin and The Walking Dead). Clearly, recent popular media offerings manifest the strain evident in our ongoing relationship with the end of days; to be an American in the modern age is to realize that everything under—and including—the sun will kill us if given half a chance. Given the prevalence of the themes like death and destruction in the current entertainment environment, it comes as no surprise that we turn to fiction to craft a kind of saving grace; although these impulses do not necessarily take the form of traditional utopias, our current culture definitely seems to yearn for something—or, more accurately, somewhere—better.

In particular, teenagers, as the subject of Young Adult (YA) fiction, have long been subjects for this kind of exploration with contemporary authors like Cory Doctorow, Paolo Bacigalupi, and M. T. Anderson exploring the myriad issues that American teenagers face as they build upon a trend that includes foundational works by Madeline L’Engle, Lois Lowry, and Robert C. O’Brien. Arguably darker in tone than previous iterations, modern YA dystopia now wrestles with the dangers of depression, purposelessness, self-harm, sexual trauma, and suicide. For American teenagers, psychological collapse can be just as damning as physical decay. Yet, rather than ascribe this shift to an increasingly rebellious, moody, or distraught teenage demographic, we might consider the cultural factors that contribute to the appeal of YA fiction in general—and themes of utopia/dystopia in particular—as manifestations spill beyond the confines of YA fiction, presenting through teenage characters in programming ostensibly designed for adult audiences as evidenced by television shows like Caprica (2009-2010).

Transcendence through Technology

A spin-off of, and prequel to, Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009), Caprica transported viewers to a world filled with futuristic technology, arguably the most prevalent of which was the holoband. Operating on basic notions of virtual reality and presence, the holoband allowed users to, in Matrix parlance, “jack into” an alternate computer-generated space, fittingly labeled by users as “V world.”[1] But despite its prominent place in the vocabulary of the show, the program itself never seemed to be overly concerned with the gadget; instead of spending an inordinate amount of time explaining how the device worked, Caprica chose to explore the effect that it had on society.

A spin-off of, and prequel to, Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009), Caprica transported viewers to a world filled with futuristic technology, arguably the most prevalent of which was the holoband. Operating on basic notions of virtual reality and presence, the holoband allowed users to, in Matrix parlance, “jack into” an alternate computer-generated space, fittingly labeled by users as “V world.”[1] But despite its prominent place in the vocabulary of the show, the program itself never seemed to be overly concerned with the gadget; instead of spending an inordinate amount of time explaining how the device worked, Caprica chose to explore the effect that it had on society.

Calling forth a tradition steeped in teenage hacker protagonists (or, at the very least, ones that belonged to the “younger” generation), our first exposure to V world—and to the series itself—comes in the form of an introduction to an underground space created by teenagers as an escape from the real world. Featuring graphic sex[2], violence, and murder, this iteration does not appear to align with traditional notions of a utopia but does represent the manifestation of Caprican teenagers’ desires for a world that is both something and somewhere else. And although immersive virtual environments are not necessarily a new feature in Science Fiction television,[3] with references stretching from Star Trek’s holodeck to Virtuality, Caprica’s real contribution to the field was its choice to foreground the process of V world’s creation and the implications of this construct for the shows inhabitants.

Taken at face value, shards like the one shown in Caprica’s first scene might appear to be nothing more than virtual parlors, the near-future extension of chat rooms[4] for a host of bored teenagers. And in some ways, we’d be justified in this reading as many, if not most, of the inhabitants of Caprica likely conceptualize the space in this fashion. Cultural critics might readily identify V world as a proxy for modern entertainment outlets, blaming media forms for increases in the expression of uncouth urges. Understood in this fashion, V world represents the worst of humanity as it provides an unreal (and surreal) existence that is without responsibilities or consequences. But Caprica also pushes beyond a surface understanding of virtuality, continually arguing for the importance of creation through one of its main characters, Zoe.[5]

Taken at face value, shards like the one shown in Caprica’s first scene might appear to be nothing more than virtual parlors, the near-future extension of chat rooms[4] for a host of bored teenagers. And in some ways, we’d be justified in this reading as many, if not most, of the inhabitants of Caprica likely conceptualize the space in this fashion. Cultural critics might readily identify V world as a proxy for modern entertainment outlets, blaming media forms for increases in the expression of uncouth urges. Understood in this fashion, V world represents the worst of humanity as it provides an unreal (and surreal) existence that is without responsibilities or consequences. But Caprica also pushes beyond a surface understanding of virtuality, continually arguing for the importance of creation through one of its main characters, Zoe.[5]

Seen one way, the very foundation of virtual reality and software—programming—is itself the language and act of world creation, with code serving as architecture (Pesce, 1999). If we accept Lawrence Lessig’s maxim that “code is law” (2006), we begin to see that cyberspace, as a construct, is infinitely malleable and the question then becomes not one of “What can we do?” but “What should we do?” In other words, if given the basic tools, what kind of existence will we create and why?

One answer to this presents in the form of Zoe, who creates an avatar that is not just a representation of herself but is, in effect, a type of virtual clone that is imbued with all of Zoe’s memories. Here we invoke a deep lineage of creation stories in Science Fiction that exhibit resonance with Frankenstein and even the Judeo-Christian God who creates man in his image. In effect, Zoe has not just created a piece of software but has, in fact, created life!—a discovery whose implications are immediate and pervasive in the world of Caprica. Although Zoe has not created a physical copy of her “self” (which would raise an entirely different set of issues), she has achieved two important milestones through her development of artificial sentience: the cyberpunk dream of integrating oneself into a large-scale computer network and the manufacture of a form of eternal life.[6]

Despite Caprica’s status as Science Fiction, we see glimpses of Zoe’s process in modern day culture as we increasingly upload bits of our identities onto the Internet, creating a type of personal information databank as we cultivate our digital selves.[7] Although these bits of information have not been constructed into a cohesive persona (much less one that is capable of achieving consciousness), we already sense that our online presence will likely outlive our physical bodies—long after we are dust, our photos, tweets, and blogs will most likely persist in some form, even if it is just on the dusty backup server of a search engine company—and, if we look closely, Caprica causes us to ruminate on how our data lives on after we’re gone. With no one to tend to it, does our data run amok? Take on a life of its own? Or does it adhere to the vision that we once had for it?

Despite Caprica’s status as Science Fiction, we see glimpses of Zoe’s process in modern day culture as we increasingly upload bits of our identities onto the Internet, creating a type of personal information databank as we cultivate our digital selves.[7] Although these bits of information have not been constructed into a cohesive persona (much less one that is capable of achieving consciousness), we already sense that our online presence will likely outlive our physical bodies—long after we are dust, our photos, tweets, and blogs will most likely persist in some form, even if it is just on the dusty backup server of a search engine company—and, if we look closely, Caprica causes us to ruminate on how our data lives on after we’re gone. With no one to tend to it, does our data run amok? Take on a life of its own? Or does it adhere to the vision that we once had for it?