Like So Much Processed Meat

“The hacker mystique posits power through anonymity. One does not log on to the system through authorized paths of entry; one sneaks in, dropping through trap doors in the security program, hiding one’s tracks, immune to the audit trails that we put there to make the perceiver part of the data perceived. It is a dream of recovering power and wholeness by seeing wonders and not by being seen.”

—Pam Rosenthal

Flesh Made Data: Part I

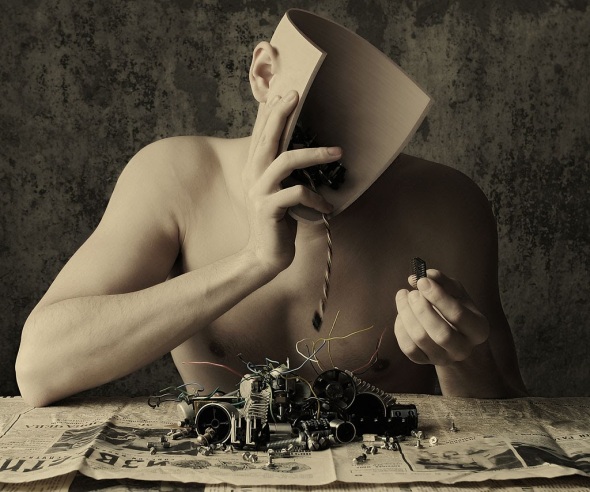

This quote, which comes from a chapter in Wendy Hui Kyong Chun’s Control and Freedom on the Orientalization of cyberspace, gestures toward the values embedded in the Internet as a construct. Reading this quote, I found myself wondering about the ways in which identity, users, and the Internet intersect in the present age. Although we certainly witness remnants of the hacker/cyberpunk ethic in movements like Anonymous, it would seem that many Americans exist in a curious tension that exists between the competing impulses for privacy and visibility.

Looking deeper, however, there seems to be an extension of cyberpunk’s ethic, rather than an outright refusal or reversal: if cyberpunk viewed the body as nothing more than a meat sac and something to be shed as one uploaded to the Net, the modern American seems, in some ways, hyper aware of the body’s ability to interface with the cloud in the pursuit of peak efficiency. Perhaps the product of a self-help culture that has incorporated the technology at hand, we are now able to track our calories, sleep patterns, medical records, and moods through wearable devices like Jawbone’s UP but all of this begs the question of whether we are controlling our data or our data is controlling us. Companies like Quantified Self promise to help consumers “know themselves through numbers,” but I am not entirely convinced. Aren’t we just learning to surveil ourselves without understanding the overarching values that guide/manage our gaze?

Returning back to Rosenthal’s quote, there is a rather interesting way in which the hacker ethic has become perverted (in my opinion) as the “dream of recovering power” is no longer about systemic change but self-transformation; one is no longer humbled by the possibilities of the Internet but instead strives to become a transformed wonder visible for all to see.

Flesh Made Data: Part II

A spin-off of, and prequel to, Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009), Caprica (2011-2012) transported viewers to a world filled with futuristic technology, arguably the most prevalent of which was the holoband. Operating on basic notions of virtual reality and presence, the holoband allowed users to, in Matrix parlance, “jack into” an alternate computer-generated space, fittingly labeled by users as “V world.”[1] But despite its prominent place in the vocabulary of the show, the program itself never seemed to be overly concerned with the gadget; instead of spending an inordinate amount of time explaining how the device worked, Caprica chose to explore the effect that it had on society.

Calling forth a tradition steeped in teenage hacker protagonists (or, at the very least, ones that belonged to the “younger” generation), our first exposure to V world—and to the series itself—comes in the form of an introduction to an underground space created by teenagers as an escape from the real world. Featuring graphic sex, violence, and murder, this iteration does not appear to align with traditional notions of a utopia but might represent the manifestation of Caprican teenagers’ desires for a world that is both something and somewhere else. And although immersive virtual environments are not necessarily a new feature in Science Fiction television, with references stretching from Star Trek’s holodeck to Virtuality, Caprica’s real contribution to the field was its choice to foreground the process of V world’s creation and the implications of this construct for the shows inhabitants.

Seen one way, the very foundation of virtual reality and software—programming—is itself the language and act of world creation, with code serving as architecture. If we accept Lawrence Lessig’s maxim that “code is law”, we begin to see that cyberspace, as a construct, is infinitely malleable and the question then becomes not one of “What can we do?” but “What should we do?” In other words, if given the basic tools, what kind of existence will we create and why?

Running with this theme, the show’s overarching plot concerns an attempt to achieve apotheosis through the uploading of physical bodies/selves into the virtual world. I found this series particularly interesting to dwell on because here again we had something that recalls the cyberpunk notion of transcendence through data but, at the same time, the show asked readers to consider why a virtual paradise was more desirous than one constructed in the real world. Put another way, the show forces the question, “To what extent do hacker ethics hold true in the physical world?”

[1] Although the show is generally quite smart about displaying the right kind of content for the medium of television (e.g., flushing out the world through channel surfing, which not only gives viewers glimpses of the world of Caprica but also reinforces the notion that Capricans experience their world through technology), the ability to visualize V world (and the transitions into it) are certainly an element unique to an audio-visual presentation. One of the strengths of the show, I think, is its ability to add layers of information through visuals that do not call attention to themselves. These details, which are not crucial to the story, flush out the world of Caprica in a way that a book could not, for while a book must generally mention items (or at least allude to them) in order to bring them into existence, the show does not have to ever name aspects of the world or actively acknowledge that they exist.

To Be Free Is Free to Be

My provocation is this: utopia is not the place to go looking for freedom. At least not the right kind of freedom. Ironically, I think, we should examine that which is so often associated with oppression, submission, and silence—dystopia.

The idea for this paper came to me a year ago while watching an episode of Caprica, a spin-off of Battlestar Galactica. Here, Tad (gamertag: Hercules) turns to Tamara and says:

“Look, I know this must seem really random to you, but this game—it really does mean something to me. It actually allows me to be something.”

Without pausing she fires back:

“Maybe if you weren’t in here playing this game you could be something out there, too.”

I think this exchange points to an interesting way in which the relationship between youth and the world is often cast: youth are dreamers and cultivate their online selves at the expense of their real lives. But I think that this distinction between virtual and real is growing false and that the development of youth’s relationship with the intangible has everything to do with their relationship to the real.

Truth be told, this is actually my favorite episode of the series and it takes its name from a poem, “There Is Another Sky”:

There is another sky

Ever serene and fair

And there is another sunshine

Though it be darkness there

Never mind faded forests, Austin

Never mind silent fields

Here is a little forest

Whose leaf is evergreen

Here is a brighter garden

Where not a frost has been

In its unfading flowers

I hear the bright bee hum

Prithee, my brother

Into my garden come!

All of this from a woman who would never see the garden for herself.

But that’s sort of exactly the point, right? I mean, Dickinson and Tad are my people—they are the ones who are mired in the dark and they are the ones searching for a light, something more, something better. Something like a utopia.

And what is Dickinson’s garden, really, other than a form of utopia? Hearing those words, we picture a pastoral safe haven that is admittedly different from the technological utopias that we’ve been discussing in class but definitely a vision for a world that is better.

The trouble is that our utopias rarely come alone: utopias are born out of dystopias, slide into dystopia, and maintain a healthy tension by threatening to turn into dystopias. As I’ve thought about this over the course of the semester, I have come to wonder if all utopias are in fact false for one person’s utopia is easily another’s dystopia. So we have this back and forth that is, as we have seen, instructive, but I’m most interested in the scenarios like those in Nineteen Eighty-Four and A Brave New World wherein an established utopia sets the scene for what has become a dystopian nightmare.

Somewhat like the life of a teenager. Tyler Clementi was perhaps the most high-profile case in a string of gay teen suicides that occurred in the fall of last year. At the time, I can remember being incredibly upset—not at Dharun, Clementi’s roommate—but at myself and my colleagues. “This death is, in part, on all of us,” I remember telling my peers for these are the kids that we are supposed to be advocating for and we’ve failed to change the culture that causes these things to happen. We’ve known about bullying in schools for a long time and we can make steps to alter that but we can also work to make youth more resilient.

Looking to do just that, columnist Dan Savage started a project called “It Gets Better” that attempted to convince gay youth to stick around because, well, “it gets better.” Once the initial goodwill wore off, I began to get increasingly upset at the project—not because the intent was unworthy but rather because the project showed a certain lack of understanding and compassion for those it was actually trying to help.

Telling a teenager that things will get better somehow, someday is like telling him that things will get better in an eternity because every day is like a million years. Telling a teenager your story means that you are not listening to theirs. And what about all those youth who don’t feel like they can tough it out until they can leave? They feel like failures. What you’re really after with this whole thing is hope, but I think that the efforts are misguided.

I was frustrated because this position caused youth to be passive bystanders in their own lives—that one day, they’d wake up or go off to college and things would magically get better. There might be some truth to that but what about all of the challenges that youth have yet to face? Life is hard—for everyone—and it’ll kick you while you’re down; but we need to teach our youth not to be afraid to get back up because the wrong lesson to learn from all of this is to become closed off and cynical.

So what are some of the ways that we can take a look at young adult culture and reexamine the activities that youth are already engaged in, in order to tell young people that they are valued just as they are?

For me, Young Adult fiction provides a great space in which to talk about themes of utopia/dystopia, depression, and bullying. So much more than Twilight, there was recently a discussion over this past summer on Twitter with participants employing the hash tag #YASaves. The topic was sparked in response to claims that the material in Young Adult fiction was too dark. Case in point, The Hunger Games centers on an event wherein 24 teenagers fight to the death in an arena. And I say this with the caveat that I am not a parent but I get that position—I really do. Years of interacting with parents and their children in the arena of college admission has convinced me that many parents want the best for their kids—they want to protect them from harm—but simply approach the process in a way that I do not find helpful.

Although “freedom from” represents a necessary pre-condition, it would seem that a true(r) sense of agency is the province of “freedom to.” And yet much of the rhetoric surrounding the current state of politics seems to center around the former as we talk fervently about liberation from dictatorships in the Middle East during the spring of 2011 or freedom from oppressive government in the United States. And these sound like good things, right? But here those dystopias born out of utopias are instructive for they show us what happens when “freedom from” collapses. Like “It Gets Better” which forwards its own vision of a life free from bullying, the dream rots because “freedom from” leads to a utopia—a space that, by its very nature, has no exit plan.

But, to be fair, perhaps “freedom to” has a stigma, one that Dan Savage is likely familiar with.

I imagine that there is a certain amount of disillusionment with this for “Free to Be…You and Me” has not really altered the perception that boys can have dolls or that it’s okay to cry. We are not yet truly free to be. But I would argue that it is not the concept of “freedom to” that is the issue here, it is the way in which it is defined—according to the song, it is a land where children and rivers run free in the green country.

In short, a utopia.

What if we applied what we learned from this course and instead of a place, recast utopia as a process of becoming? A dream of perpetual motion, if you will. What if we taught youth to think about how “freedom from” mirrors the language of colonialism and instead suggested that the more pertinent issue is that of freedom to? Not just freedom from censorship but freedom to protest, freedom to information and access to it, freedom to be visible, freedom to be anonymous, freedom to wonder, freedom to dream, and freedom to become. We are quickly seeing that virtual spaces are becoming hotbeds for these sorts of fights and the results of those skirmishes have a very real impact on the everyday lives of young adults. If there are teens who view high school as a war zone shouldn’t we arm them with better tactics? What if utopian described not a place but a type of person? Someone who fought accepted notions of the future and did not just wait for it to get better but challenged it, and us, to be better. Just maybe someone like a poet.

I opened with Emily Dickinson and I will return to her to close.

We’d never know how high we are

Until we’re called to rise

And then, if we are true to plan

Our statures touch the skies

Take what you’ve learned from this class and encourage youth to struggle with these notions of “freedom from” and “freedom to.” Help them rise.

Underneath It All

WARNING: The following contains images that may be considered graphic in nature. As a former Biology student (and Pre-Med at that!), I have spent a number of hours around bodies and studying anatomy but I realize that this desensitization might not exist for everyone. I watched surgeries while eating dinner in college and study horror films (which I realize is not normal). Please proceed at your own risk.

At first glance, the anatomical model to the left (also known as “The Doll,” “Medical Venus,” or simply “Venus) might seem like nothing more than an inspired illustration from the most well-known text of medicine, Gray’s Anatomy. To most modern viewers, the image (and perhaps even the model itself) raise a few eyebrows but is unlikely to elicit a reaction much stronger than that. And why should it? We are a culture that has grown accustomed to watching surgeries on television, witnessed the horrible mutilating effects of war, and even turned death into a spectacle of entertainment. Scores of school children have visited Body Worlds or have been exposed to the Visible Human Project (if you haven’t watched the video, it is well worth the minute). We have also been exposed to a run of “torture porn” movies in the 2000s that included offerings like Saw, Hostel, and Captivity. Although we might engage in a larger discussion about our relationship to the body, it seems evident that we respond to, and use, images of the body quite differently in a modern context. (If there’s any doubt, one only need to look at a flash-based torture game that appeared in 2007, generating much discussion.) Undoubtedly, our relationship to the body has changed over the years—and will likely continue to do so with forays into transhumanism—which makes knowledge of the image’s original context all the more crucial to fully understanding its potential import.

At first glance, the anatomical model to the left (also known as “The Doll,” “Medical Venus,” or simply “Venus) might seem like nothing more than an inspired illustration from the most well-known text of medicine, Gray’s Anatomy. To most modern viewers, the image (and perhaps even the model itself) raise a few eyebrows but is unlikely to elicit a reaction much stronger than that. And why should it? We are a culture that has grown accustomed to watching surgeries on television, witnessed the horrible mutilating effects of war, and even turned death into a spectacle of entertainment. Scores of school children have visited Body Worlds or have been exposed to the Visible Human Project (if you haven’t watched the video, it is well worth the minute). We have also been exposed to a run of “torture porn” movies in the 2000s that included offerings like Saw, Hostel, and Captivity. Although we might engage in a larger discussion about our relationship to the body, it seems evident that we respond to, and use, images of the body quite differently in a modern context. (If there’s any doubt, one only need to look at a flash-based torture game that appeared in 2007, generating much discussion.) Undoubtedly, our relationship to the body has changed over the years—and will likely continue to do so with forays into transhumanism—which makes knowledge of the image’s original context all the more crucial to fully understanding its potential import.

Part of the image’s significance comes from it’s appearance in a culture that generally did not have a sufficient working knowledge of the body by today’s standards, with medical professionals also suffering a shortage of cadavers to study (which in turn led to an interesting panic regarding body snatching and consequentially resulted in a different relationship between people and dead bodies). The anatomical doll pictured above appeared as part of an exhibit in the Imperiale Regio Museo di Fisica e Storia Naturale (nicknamed La Specola), one of the few natural history museums open to the public at the time. This crucial piece of information allows historical researchers to immediately gain a sense of the model’s importance for, through it, knowledge of the body began to spread throughout the masses and its depiction would forever be inscribed onto visual culture.

Also important, however, is the female nature of the body, which itself reflected a then-fascination with women in Science. Take, for example, the notion that the Venus lay ensconced in a room full of uteruses and we immediately gain more information about the significance of the image above: in rather straightforward terms, the male scientist fascination with the female body and process of reproduction becomes evident. Although a more detailed discussion is warranted, this interest spoke to developments in the Enlightenment that began a systematic study of Nature, wresting way its secrets through the development of empirical modes of inquiry. Women, long aligned with Nature through religion (an additional point to be made here is that in its early incarnations, the clear demarcations between fields that we see today did not exist, meaning that scientists were also philosophers and religious practitioners) were therefore objects to be understood as males sought to once again peer further into the unknown. This understanding of the original image is reinforced when one contrasts it with its male counterparts from the same exhibit, revealing two noticeable differences. First, the female figure possesses skin, hair, and lips, which serve as reminders of the body’s femininity and humanity. Second, the male body remains intact, while the female body has been ruptured/opened to reveal its secrets. The male body, it seems, had nothing to hide. Moreover, the position of the female model is somewhat evocative, with its arched back, pursed lips, and visual similarity to Snow White in her coffin, which undoubtedly speaks to the posing of women’s bodies and how such forms were intended to be consumed.

Also important, however, is the female nature of the body, which itself reflected a then-fascination with women in Science. Take, for example, the notion that the Venus lay ensconced in a room full of uteruses and we immediately gain more information about the significance of the image above: in rather straightforward terms, the male scientist fascination with the female body and process of reproduction becomes evident. Although a more detailed discussion is warranted, this interest spoke to developments in the Enlightenment that began a systematic study of Nature, wresting way its secrets through the development of empirical modes of inquiry. Women, long aligned with Nature through religion (an additional point to be made here is that in its early incarnations, the clear demarcations between fields that we see today did not exist, meaning that scientists were also philosophers and religious practitioners) were therefore objects to be understood as males sought to once again peer further into the unknown. This understanding of the original image is reinforced when one contrasts it with its male counterparts from the same exhibit, revealing two noticeable differences. First, the female figure possesses skin, hair, and lips, which serve as reminders of the body’s femininity and humanity. Second, the male body remains intact, while the female body has been ruptured/opened to reveal its secrets. The male body, it seems, had nothing to hide. Moreover, the position of the female model is somewhat evocative, with its arched back, pursed lips, and visual similarity to Snow White in her coffin, which undoubtedly speaks to the posing of women’s bodies and how such forms were intended to be consumed.

Thus, the fascination with women’s bodies—and the mystery they conveyed—manifested in the physical placement of the models on display at La Specola, both in terms of distribution and posture. In short, comprehension of the museum’s layout helps one to understand not only the relative significance of the image above, but also speaks more generally to the role that women’s bodies held in 19th-century Italy, with the implications of this positioning resounding throughout Western history. (As a brief side note, this touches upon another area of interest for me with horror films of the 20th century: slasher films veiled an impulse to “know” women, with the phrase “I want to see/feel your insides” being one of my absolute favorites as it spoke to the psychosexual component of serial killers while continuing the trend established above. Additionally, we also witness a rise in movies wherein females give birth to demon spawn (e.g. The Omen), are possessed by male forces (e.g., The Exorcist), and are also shown as objects of inquiry for men who also seek to “know” women through science (e.g., Poltergeist). Recall the interactivity with the Venus and we begin to sense a thematic continuity between the renegotiation of women’s bodies, the manipulation of women’s bodies, and knowledge. For some additional writings on this, La Specola, and the television show Caprica, please refer to a previous entry on my blog.)

Thus, the fascination with women’s bodies—and the mystery they conveyed—manifested in the physical placement of the models on display at La Specola, both in terms of distribution and posture. In short, comprehension of the museum’s layout helps one to understand not only the relative significance of the image above, but also speaks more generally to the role that women’s bodies held in 19th-century Italy, with the implications of this positioning resounding throughout Western history. (As a brief side note, this touches upon another area of interest for me with horror films of the 20th century: slasher films veiled an impulse to “know” women, with the phrase “I want to see/feel your insides” being one of my absolute favorites as it spoke to the psychosexual component of serial killers while continuing the trend established above. Additionally, we also witness a rise in movies wherein females give birth to demon spawn (e.g. The Omen), are possessed by male forces (e.g., The Exorcist), and are also shown as objects of inquiry for men who also seek to “know” women through science (e.g., Poltergeist). Recall the interactivity with the Venus and we begin to sense a thematic continuity between the renegotiation of women’s bodies, the manipulation of women’s bodies, and knowledge. For some additional writings on this, La Specola, and the television show Caprica, please refer to a previous entry on my blog.)

This differential treatment of bodies continues to exist today, with the aforementioned Saw providing a pertinent (and graphic) example. Compare the image of a female victim to the right with that of the (male) antagonist Jigsaw below. Although the situational context of these images differ, with the bodies’ death states providing commentary on the respective characters, both bodies are featured with exposed chests in a manner similar to the Venus depicted at the outset of this piece. Extensive discussion is beyond the scope of this writing, but I would like to mention that an interesting—and potentially productive—sort of triangulation occurs when one compares the images of the past/present female figures (the latter of whom is caught in an “angel” trap) with each other and with that of the past/present male figures.

This differential treatment of bodies continues to exist today, with the aforementioned Saw providing a pertinent (and graphic) example. Compare the image of a female victim to the right with that of the (male) antagonist Jigsaw below. Although the situational context of these images differ, with the bodies’ death states providing commentary on the respective characters, both bodies are featured with exposed chests in a manner similar to the Venus depicted at the outset of this piece. Extensive discussion is beyond the scope of this writing, but I would like to mention that an interesting—and potentially productive—sort of triangulation occurs when one compares the images of the past/present female figures (the latter of whom is caught in an “angel” trap) with each other and with that of the past/present male figures.  Understanding these images as points in a constellation helps one to see interesting themes: for example, as opposed to the 19th-century practice (i.e, past male), the image of Jigsaw (i.e., present male) cut open is intended to humanize the body, suggesting that although he masterminded incredibly detailed traps his body was also fragile and susceptible to breakdown. Jigsaw’s body, then, presents some overlap with Venus (i.e., past female) particularly when one considers that Jigsaw’s body plays host to a wax-covered audiotape—in the modern interpretation, it seems that the male body is also capable of harboring secrets.

Understanding these images as points in a constellation helps one to see interesting themes: for example, as opposed to the 19th-century practice (i.e, past male), the image of Jigsaw (i.e., present male) cut open is intended to humanize the body, suggesting that although he masterminded incredibly detailed traps his body was also fragile and susceptible to breakdown. Jigsaw’s body, then, presents some overlap with Venus (i.e., past female) particularly when one considers that Jigsaw’s body plays host to a wax-covered audiotape—in the modern interpretation, it seems that the male body is also capable of harboring secrets.

Ultimately, a more detailed understanding of the original image would flush out its implications for the public of Italy in the 19th century and also look more broadly at the depictions of women, considering how “invasive practices” were not just limited to surgery. La Specola’s position as a state-sponsored institution also has implications for the socio-historical context for the image that should also be investigated. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, scholars should endeavor to understand the Medical Venus as not just reflective of cultural practice but also seek to ascertain how its presence (along with other models and the museum as a whole) provided new opportunities for thought, expression, and cultivation of bodies at the time.

The Real-Life Implications of Virtual Selves

“The end is nigh!”—the plethora of words, phrases, and warnings associated with the impending apocalypse has saturated American culture to the point of being jaded, as picketing figures bearing signs have become a fixture of political cartoons and echoes of the Book of Revelation appear in popular media like Legion and the short-lived television series Revelations. On a secular level, we grapple with the notion that our existence is a fragile one at best, with doom portended by natural disasters (e.g, Floodland and The Day after Tomorrow), rogue asteroids (e.g., Life as We Knew It and Armageddon), nuclear fallout (e.g., Z for Zachariah and The Terminator), biological malfunction (e.g., The Chrysalids and Children of Men) and the increasingly-visible zombie apocalypse (e.g., Rot and Ruin and The Walking Dead). Clearly, recent popular media offerings manifest the strain evident in our ongoing relationship with the end of days; to be an American in the modern age is to realize that everything under—and including—the sun will kill us if given half a chance. Given the prevalence of the themes like death and destruction in the current entertainment environment, it comes as no surprise that we turn to fiction to craft a kind of saving grace; although these impulses do not necessarily take the form of traditional utopias, our current culture definitely seems to yearn for something—or, more accurately, somewhere—better.

In particular, teenagers, as the subject of Young Adult (YA) fiction, have long been subjects for this kind of exploration with contemporary authors like Cory Doctorow, Paolo Bacigalupi, and M. T. Anderson exploring the myriad issues that American teenagers face as they build upon a trend that includes foundational works by Madeline L’Engle, Lois Lowry, and Robert C. O’Brien. Arguably darker in tone than previous iterations, modern YA dystopia now wrestles with the dangers of depression, purposelessness, self-harm, sexual trauma, and suicide. For American teenagers, psychological collapse can be just as damning as physical decay. Yet, rather than ascribe this shift to an increasingly rebellious, moody, or distraught teenage demographic, we might consider the cultural factors that contribute to the appeal of YA fiction in general—and themes of utopia/dystopia in particular—as manifestations spill beyond the confines of YA fiction, presenting through teenage characters in programming ostensibly designed for adult audiences as evidenced by television shows like Caprica (2009-2010).

Transcendence through Technology

A spin-off of, and prequel to, Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009), Caprica transported viewers to a world filled with futuristic technology, arguably the most prevalent of which was the holoband. Operating on basic notions of virtual reality and presence, the holoband allowed users to, in Matrix parlance, “jack into” an alternate computer-generated space, fittingly labeled by users as “V world.”[1] But despite its prominent place in the vocabulary of the show, the program itself never seemed to be overly concerned with the gadget; instead of spending an inordinate amount of time explaining how the device worked, Caprica chose to explore the effect that it had on society.

A spin-off of, and prequel to, Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009), Caprica transported viewers to a world filled with futuristic technology, arguably the most prevalent of which was the holoband. Operating on basic notions of virtual reality and presence, the holoband allowed users to, in Matrix parlance, “jack into” an alternate computer-generated space, fittingly labeled by users as “V world.”[1] But despite its prominent place in the vocabulary of the show, the program itself never seemed to be overly concerned with the gadget; instead of spending an inordinate amount of time explaining how the device worked, Caprica chose to explore the effect that it had on society.

Calling forth a tradition steeped in teenage hacker protagonists (or, at the very least, ones that belonged to the “younger” generation), our first exposure to V world—and to the series itself—comes in the form of an introduction to an underground space created by teenagers as an escape from the real world. Featuring graphic sex[2], violence, and murder, this iteration does not appear to align with traditional notions of a utopia but does represent the manifestation of Caprican teenagers’ desires for a world that is both something and somewhere else. And although immersive virtual environments are not necessarily a new feature in Science Fiction television,[3] with references stretching from Star Trek’s holodeck to Virtuality, Caprica’s real contribution to the field was its choice to foreground the process of V world’s creation and the implications of this construct for the shows inhabitants.

Taken at face value, shards like the one shown in Caprica’s first scene might appear to be nothing more than virtual parlors, the near-future extension of chat rooms[4] for a host of bored teenagers. And in some ways, we’d be justified in this reading as many, if not most, of the inhabitants of Caprica likely conceptualize the space in this fashion. Cultural critics might readily identify V world as a proxy for modern entertainment outlets, blaming media forms for increases in the expression of uncouth urges. Understood in this fashion, V world represents the worst of humanity as it provides an unreal (and surreal) existence that is without responsibilities or consequences. But Caprica also pushes beyond a surface understanding of virtuality, continually arguing for the importance of creation through one of its main characters, Zoe.[5]

Taken at face value, shards like the one shown in Caprica’s first scene might appear to be nothing more than virtual parlors, the near-future extension of chat rooms[4] for a host of bored teenagers. And in some ways, we’d be justified in this reading as many, if not most, of the inhabitants of Caprica likely conceptualize the space in this fashion. Cultural critics might readily identify V world as a proxy for modern entertainment outlets, blaming media forms for increases in the expression of uncouth urges. Understood in this fashion, V world represents the worst of humanity as it provides an unreal (and surreal) existence that is without responsibilities or consequences. But Caprica also pushes beyond a surface understanding of virtuality, continually arguing for the importance of creation through one of its main characters, Zoe.[5]

Seen one way, the very foundation of virtual reality and software—programming—is itself the language and act of world creation, with code serving as architecture (Pesce, 1999). If we accept Lawrence Lessig’s maxim that “code is law” (2006), we begin to see that cyberspace, as a construct, is infinitely malleable and the question then becomes not one of “What can we do?” but “What should we do?” In other words, if given the basic tools, what kind of existence will we create and why?

One answer to this presents in the form of Zoe, who creates an avatar that is not just a representation of herself but is, in effect, a type of virtual clone that is imbued with all of Zoe’s memories. Here we invoke a deep lineage of creation stories in Science Fiction that exhibit resonance with Frankenstein and even the Judeo-Christian God who creates man in his image. In effect, Zoe has not just created a piece of software but has, in fact, created life!—a discovery whose implications are immediate and pervasive in the world of Caprica. Although Zoe has not created a physical copy of her “self” (which would raise an entirely different set of issues), she has achieved two important milestones through her development of artificial sentience: the cyberpunk dream of integrating oneself into a large-scale computer network and the manufacture of a form of eternal life.[6]

Despite Caprica’s status as Science Fiction, we see glimpses of Zoe’s process in modern day culture as we increasingly upload bits of our identities onto the Internet, creating a type of personal information databank as we cultivate our digital selves.[7] Although these bits of information have not been constructed into a cohesive persona (much less one that is capable of achieving consciousness), we already sense that our online presence will likely outlive our physical bodies—long after we are dust, our photos, tweets, and blogs will most likely persist in some form, even if it is just on the dusty backup server of a search engine company—and, if we look closely, Caprica causes us to ruminate on how our data lives on after we’re gone. With no one to tend to it, does our data run amok? Take on a life of its own? Or does it adhere to the vision that we once had for it?

Despite Caprica’s status as Science Fiction, we see glimpses of Zoe’s process in modern day culture as we increasingly upload bits of our identities onto the Internet, creating a type of personal information databank as we cultivate our digital selves.[7] Although these bits of information have not been constructed into a cohesive persona (much less one that is capable of achieving consciousness), we already sense that our online presence will likely outlive our physical bodies—long after we are dust, our photos, tweets, and blogs will most likely persist in some form, even if it is just on the dusty backup server of a search engine company—and, if we look closely, Caprica causes us to ruminate on how our data lives on after we’re gone. With no one to tend to it, does our data run amok? Take on a life of its own? Or does it adhere to the vision that we once had for it?

Proposing an entirely different type of transcendence, another character in Caprica, Sister Clarice, hopes to use Zoe’s work in service of a project called “apotheosis.” Representing a more traditional type of utopia in that it represents a paradisiacal space offset from the normal, Clarice aims to construct a type of virtual heaven for believers of the One True God,[8] offering an eternal virtual life at the cost of one’s physical existence. Perhaps speaking to a sense of disengagement with the existent world, Clarice’s vision also reflects a tradition that conceptualizes cyberspace as a chance where humanity can try again, a blank slate where society can be re-engineered. Using the same principles that are available to Zoe, Clarice sees a chance to not only upload copies of existent human beings, but bring forth an entire world through code. Throughout the series, Clarice strives to realize her vision, culminating in a confrontation with Zoe’s avatar who has, by this time, obtained a measure of mastery over the virtual domain. Suggesting that apotheosis cannot be granted, only earned, Clarice’s dream of apotheosis literally crumbles around her as her followers give up their lives in vain.

Although it is unlikely that we will see a version of Clarice’s apotheosis anytime in the near future, the notion of constructed immersive virtual worlds does not seem so far off. At its core, Caprica asks us, as a society, to think carefully about the types of spaces that we endeavor to realize and the ideologies that drive such efforts. If we understand religion as a structured set of beliefs that structure and order this world through our belief in the next, we can see the overlap between traditional forms of religion and the efforts of technologists like hackers, computer scientists, and engineers. As noted by Mark Pesce, Vernor Vinge’s novella True Names spoke to a measure of apotheosis and offered a new way of understanding the relationship between the present and the future—what Vinge offered to hackers was, in fact, a new form of religion (Pesce, 1999). Furthermore, aren’t we, as creators of these virtual worlds fulfilling one of the functions of God? Revisiting the overlap between doomsday/apocalyptic/dystopian fiction as noted in the paper’s opening and Science Fiction, we see a rather seamless integration of ideas that challenges the traditional notion of a profane/sacred divide; in their own ways, both the writings of religion and science both concern themselves with some of the same themes, although they may, at times, use seemingly incompatible language.

Ultimately, however, the most powerful statement made by Caprica comes about as a result of the extension to arguments made on screen: by invoking virtual reality, the series begs viewers to consider the overlay of an entirely subjective reality onto a more objective one.[9] Not only presenting the coexistence of multiple realities as a fact, Caprica asks us to understand how actions undertaken in one world affect the other. On a literal level, we see that the rail line of New Cap City (a virtual analogue of Caprica City, the capital of the planet of Caprica)[10] is degraded (i.e., “updated) to reflect a destroyed offline train, but, more significantly, the efforts of Zoe and Clarice speak to the ways in which our faith in virtual worlds can have a profound impact on “real” ones. How, then, do our own beliefs about alternate realities (be it heaven, spirits, string theory, or media-generated fiction) shape actions that greatly affect our current existence? What does our vision of the future make startlingly clear to us and what does it occlude? What will happen as future developments in technology increase our sense of presence and further blur the line between fiction and reality? What will we do if the presence of eternal virtual life means that “life” loses its meaning? Will we reinscribe rules onto the world to bring mortality back (and with it, a sense of urgency and finality) like Capricans did in New Cap City? Will there come a day where we choose a virtual existence over a physical one, participating in a mass exodus to cyberspace as we initiate a type of secular rapture?

As we have seen, online environments have allowed for incredible amounts of innovation and, on some days, the future seems inexplicably bright. Shows like Caprica are valuable for us as they provide a framework through which the average viewer can discuss issues of presence and virtuality without getting overly bogged down by technospeak. On some level, we surely understand the issues we see on screen as dilemmas that are playing out in a very human drama and Science Fiction offerings like Caprica provide us with a way to talk about subjects that we will confront in the future although we may not even realize that we are doing so at the time. Without a doubt, we should nurture this potential while remaining mindful of our actions; we should strive to attain apotheosis but never forget why we wanted to get there in the first place.

Works Cited

Lessig, L. (2006, January). Socialtext. Retrieved September 10, 2011, from Code 2.0: https://www.socialtext.net/codev2/

Pesce, M. (1999, December 19). MIT Communications Forum. Retrieved September 12, 2011, from Magic Mirror: The Novel as a Software Development Platform: http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/papers/pesce.html

[1] Although the show is generally quite smart about displaying the right kind of content for the medium of television (e.g., flushing out the world through channel surfing, which not only gives viewers glimpses of the world of Caprica but also reinforces the notion that Capricans experience their world through technology), the ability to visualize V world (and the transitions into it) are certainly an element unique to an audio-visual presentation. One of the strengths of the show, I think, is its ability to add layers of information through visuals that do not call attention to themselves. These details, which are not crucial to the story, flush out the world of Caprica in a way that a book could not, for while a book must generally mention items (or at least allude to them) in order to bring them into existence, the show does not have to ever name aspects of the world or actively acknowledge that they exist. Moreover, I think that there is something rather interesting about presenting a heavily visual concept through a visual medium that allows viewers to identify with the material in a way that they could not if it were presented through text (or even a comic book). Likewise, reading Neal Stephenson’s A Diamond Age (which prominently features a book) allows one to reflect on one’s own interaction with the book itself—an opportunity that would not be afforded to you if you watched a television or movie adaptation.

[2] By American cable television standards, with the unrated and extended pilot featuring some nudity.

[3] Much less Science Fiction as a genre!

[4] One could equally make the case that V world also represents a logical extension of MUDs, MOOs, and MMORPGs. The closest modern analogy might, in fact, be a type of Second Life space where users interact in a variety of ways through avatars that represent users’ virtual selves.

[5] Although beyond the scope of this paper, Zoe also represents an interesting figure as both the daughter of the founder of holoband technology and a hacker who actively worked to subvert her father’s creation. Representing a certain type of stability/structure through her blood relation, Zoe also introduced an incredible amount of instability into the system. Building upon the aforementioned hacker tradition, which itself incorporates ideas about youth movements from the 1960s and lone tinkerer/inventor motifs from Science Fiction in the early 20th century, Zoe embodies teenage rebellion even as she figures in a father-daughter relationship, which speaks to a particular type of familial bond/relationship of protection and perhaps stability.

[6] Although the link is not directly made, fans of Battlestar Galactica might see this as the start of resurrection, a process that allows consciousness to be recycled after a body dies.

[7] In addition, of course, is the data that is collected about us involuntarily or without our express consent.

[8] As background context for those who are unfamiliar with the show, the majority of Capricans worship a pantheon of gods, with monotheism looked upon negatively as it is associated with a fundamentalist terrorist organization called Soldiers of The One.

[9] One might in fact argue that there is no such thing as an “objective” reality as all experiences are filtered in various ways through culture, personal history, memory, and context. What I hope to indicate here, however, is that the reality experienced in the V world is almost entirely divorced from the physical world of its users (with the possible exception of avatars that resembled one’s “real” appearance) and that virtual interactions, while still very real, are, in a way, less grounded than their offline counterparts.

[10] Readers unfamiliar with the show should note that “Caprica” refers to both the name of the series and a planet that is part of a set of colonies. Throughout the paper, italicized versions of the word have been used to refer to the television show while an unaltered font has been employed to refer to the planet.

A Spoonful of Fiction Helps the Science Go Down

Despite not being an avid fan of Science Fiction when I was younger (unless you count random viewings of Star Trek reruns), I engaged in a thorough study of scientific literature in the course of pursuing a degree in the Natural Sciences. Instead of Nineteen Eighty-Four, I read books about the discovery of the cell and of cloning; instead of Jules Verne’s literary journeys, I followed the real-life treks of Albert Schweitzer. I studied Biology and was proud of it! I was smart and cool (as much as a high school student can be) for although I loved Science, I never would have identified as a Sci-Fi nerd.

But, looking back, I begin to wonder.

For those who have never had the distinct pleasure of studying Biology (or who have pushed the memory far into the recesses of their minds), let me offer a brief taste via this diagram of the Krebs Cycle:

Admittedly, not overly complicated (but certainly a lot for my high school mind to understand), I found myself making up a story of sorts in order to remember the steps. The details are fuzzy, but I seem to recall some sort of bus with passengers getting on and off as the vehicle made a circuit and ended up back at a station. I will be the first to admit that this particular tale wasn’t overly sophisticated or spectacular, but, when you think about it, wasn’t it a form of science fiction? So my story didn’t feature futuristic cars, robots, aliens, or rockets—but, at its core, it represented a narrative that helped me to make sense of my world, reconciling the language of science with my everyday vernacular. At the very least, it was a fiction about science fact.

And, ultimately, isn’t this what Science Fiction is all about (at least in part)? We can have discussions about hard vs. soft or realistic vs. imaginary, but, for me, the genre has always been about people’s connection to concepts in science and their resulting relationships with each other. Narrative allows us to explore ethical, moral, and technological issues in science that scientists themselves might not even think about. We respond to innovations with a mixture of anxiety, hope, and curiosity and the stories that we tell often reveal that we are capable of experiencing all three emotional states simultaneously! For those of us who do not know jargon, Science Fiction allows us to respond to the field on our terms as we simply try to make sense of it all. Moreover, because of its status as genre, Science Fiction also affords us the ability to touch upon deeply ingrained issues in a non-threatening manner: as was mentioned in our first class with respect to humor, our attention is so focused on tech that we “forget” that we are actually talking about things of serious import. From Frankenstein to Dr. Moreau, the Golem, Faust, Francis Bacon, Battlestar Galactica and Caprica (among many others), we have continued to struggle with our relationship to Nature and God (and, for that matter, what are Noah and Babel about if not technology!) all while using Science Fiction as a conduit. Through Sci-Fi we not only concern ourselves with issues of technology but also juggle concepts of creation/eschatology, autonomy, agency, free will, family, and society.

And, ultimately, isn’t this what Science Fiction is all about (at least in part)? We can have discussions about hard vs. soft or realistic vs. imaginary, but, for me, the genre has always been about people’s connection to concepts in science and their resulting relationships with each other. Narrative allows us to explore ethical, moral, and technological issues in science that scientists themselves might not even think about. We respond to innovations with a mixture of anxiety, hope, and curiosity and the stories that we tell often reveal that we are capable of experiencing all three emotional states simultaneously! For those of us who do not know jargon, Science Fiction allows us to respond to the field on our terms as we simply try to make sense of it all. Moreover, because of its status as genre, Science Fiction also affords us the ability to touch upon deeply ingrained issues in a non-threatening manner: as was mentioned in our first class with respect to humor, our attention is so focused on tech that we “forget” that we are actually talking about things of serious import. From Frankenstein to Dr. Moreau, the Golem, Faust, Francis Bacon, Battlestar Galactica and Caprica (among many others), we have continued to struggle with our relationship to Nature and God (and, for that matter, what are Noah and Babel about if not technology!) all while using Science Fiction as a conduit. Through Sci-Fi we not only concern ourselves with issues of technology but also juggle concepts of creation/eschatology, autonomy, agency, free will, family, and society.

It would make sense, then, that modern science fiction seemed to rise concurrent with post-Industrial Revolution advancements as the public was presented with a whole host of new opportunities and challenges. Taken this way, Science Fiction has always been about the people—call it low culture if you must—and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Rip My Feelings Out Before They Make Me Doubt

The sun!

It’s hard to come back from an episode that ends with a fade to white and a gasp. Taking a bit of a breather (was there ever any doubt that Jessica was in real danger?), it gives us a chance to reflect on times when the one thing the want—the thing that we burn for—is the very thing that will kill us. This story has been told time and again throughout history, with varying levels of moral shading, but, in some ways, it’s one of the things this show has always been about. It’s really kind of amazing, when you think about it—in this season, there’s the idea that the repressed part of you is going to destroy you, the notion that we will kill ourselves in order to save or protect the ones we love, and this last bit about the death drive.

And maybe this is particular to me, or the way that I see the world, but my favorite episodes with this, Caprica, BSG, or Six Feet Under are always ones where things are crumbling down everywhere you look. I suppose that part of it is that I trust these shows and know that the breakdown is delicious because it helps the characters prioritize and realize what is really important and what is really worth fighting for. I am always interested in the the choice to become hard or to become strong and episodes penned by Alan Ball do that so well.

Knowing, for example, that Eric will eventually get his memory back only makes it sweeter when Sookie allows herself to believe that Eric will never betray her. Sookie being happy and/or in love are somewhat surface issues for me—the real question is how, when, and why we choose to pursue a path that we know is going to come back to bite us in the end. The pain is going to be that much worse for all that we put into it. I don’t think the show comes down on either side but hopefully causes viewers to think about which choice is right in their own lives.

Simply Passing

Shots fired. A breath taken. Reset, reload, refocus. Faith tested and testaments of faith.

Indeed, on one level, “Blowback” was an episode rife with tests: from the A story of Lacy to the background created by Daniel and the literal blowback of Durham/Clarice, we see characters subject to various types of tests. Who succeeds? More importantly, who fails? Why?

But also consider that our main cast suffers setbacks, learning to triumph in their own ways. Facing challenges small and large (Lacy’s whole trip to Gemenon–and her life in general–is, in its way, one big setback, is it not?), we see characters hardening before our eyes. Although the easy connection presence of faith in the show can be discussed in the context of mono/polytheists, terrorism, and the kissing of Apollo’s arrow, I would argue that a more interesting discussion to be had centers around the role of faith (is it even there?) in the face of adversity.

Focus on the Family

This week, our class continued to explore ideas of gender in the world of Caprica. Focusing primarily on the women, students began to contemplate the ways in which sexuality and gender intersect. Although I study this particular overlap extensively in respect to Horror, our class evidenced some interesting ideas in this arena and I will leave it to them to carry on the discussion.

This week, our class continued to explore ideas of gender in the world of Caprica. Focusing primarily on the women, students began to contemplate the ways in which sexuality and gender intersect. Although I study this particular overlap extensively in respect to Horror, our class evidenced some interesting ideas in this arena and I will leave it to them to carry on the discussion.

Before proceeding, I should take a quick second to differentiate the terms “sex” and “gender”: I use “sex” in reference to a biological classification while I see “gender” as socially constructed. Although patriarchal/heteronormative stances have traditionally aligned the two concepts, positioning them along a static binary, scholarship in fields such as Gender Studies and Sociology has effectively demonstrated that the interaction between sex and gender is much more fluid and dynamic (Rowley, 2007). For example, in our current culture, we have metrosexuals coexisting alongside retrosexuals and movements to redefine female beauty (the Dove “Real Beauty” ads were mentioned in class and their relative merits–or lack thereof—deserve a much deeper treatment than I can provide here).

Although a number of students in our class focused on the sexuality ofAmanda Graystone, Diane Winston poignantly noted that the character of Amanda also invoked the complex web of associations between motherhood, women, and gender. Motherhood, I would argue, plays an important part in the definition of female identity in America; our construction of the “female” continually assigns meaning to women’s lives based on their status as, or desire to be, mothers. (Again, drawing upon my history with gender and violence, I suggest that we can partially understand the pervasive nature of this concept by considering how society variously views murderers, female murderers, and mothers who murder their children.) In line with this idea, we see that almost every female featured in the episode was directly connected to motherhood in some fashion (with Evelyn perhaps being the weakest manifestation, although we know that she has just started down the path that will lead her into becoming the mother of young Willie).

Although a number of students in our class focused on the sexuality ofAmanda Graystone, Diane Winston poignantly noted that the character of Amanda also invoked the complex web of associations between motherhood, women, and gender. Motherhood, I would argue, plays an important part in the definition of female identity in America; our construction of the “female” continually assigns meaning to women’s lives based on their status as, or desire to be, mothers. (Again, drawing upon my history with gender and violence, I suggest that we can partially understand the pervasive nature of this concept by considering how society variously views murderers, female murderers, and mothers who murder their children.) In line with this idea, we see that almost every female featured in the episode was directly connected to motherhood in some fashion (with Evelyn perhaps being the weakest manifestation, although we know that she has just started down the path that will lead her into becoming the mother of young Willie).

Amanda, the easiest depiction to deconstruct, voices a struggle of modern career women as she feels the pressure to “have it all.” Although Amanda tells Mar-Beth that she suffered from Post-Partum Depression, and explains her general inability to connect with her daughter as a newborn (the ramifications of which we have already seen played out over the course of the series thus far), she later informs Agent Durham that she circumvented Mar-Beth’s suspicions by lying (we assume that she was referring to the aforementioned interaction, but this is not specified). For me, this moment was significant in that it made Amanda instantly more relatable—something that I have struggled with for a while now—as a woman who may have, in fact, tried desperately to connect with her daughter but simply could not.

Both Daniel and Amanda, it seems, had trouble fully understanding their daughter Zoe. While Amanda’s struggles play out on an emotional level, Daniel labors to decipher the secret behind Zoe’s resurrection program (a term charged with religious significance and also resonance within the world ofBattlestar Galactica). Here we see a parallel to the female notion of motherhood–Daniel, in his own way, is giving birth to a new life (he hopes). Yet, as the title alludes to, Daniel experiences a false labor: his baby is not quite ready to be let loose in the world. Moreover, like his wife, Daniel attempts to force something that should occur naturally, resulting in a less-than-desired outcome.

For Daniel, this product is a virtual Amanda, who was discussed by some of our class as they pointed out stark differences in sexuality and sexualization. Although the contrast between the real and virtual versions of Amanda holds mild interest, the larger question becomes one of the intrinsic value of “realness.” Despite Daniel’s best attempts, he continues to berate the virtual Amanda for not being real, much to her dismay as she, through no fault of her own, cannot understand that she is fundamentally broken. Although not necessarily appropriate for this course, we can think about the issues raised by virtual reality, identities, and reputations along with our constant drive for “authenticity” in a world forever affected by mediated representations. Popular culture has depicted dystopian scenarios like The Matrix that argue against our infatuation with the veneer—underneath a shiny exterior, some would argue, we are rotting. Images, according to critics like Daniel Boorstin and Walter Benjamin, leave something to be desired.

For Daniel, this product is a virtual Amanda, who was discussed by some of our class as they pointed out stark differences in sexuality and sexualization. Although the contrast between the real and virtual versions of Amanda holds mild interest, the larger question becomes one of the intrinsic value of “realness.” Despite Daniel’s best attempts, he continues to berate the virtual Amanda for not being real, much to her dismay as she, through no fault of her own, cannot understand that she is fundamentally broken. Although not necessarily appropriate for this course, we can think about the issues raised by virtual reality, identities, and reputations along with our constant drive for “authenticity” in a world forever affected by mediated representations. Popular culture has depicted dystopian scenarios like The Matrix that argue against our infatuation with the veneer—underneath a shiny exterior, some would argue, we are rotting. Images, according to critics like Daniel Boorstin and Walter Benjamin, leave something to be desired.

Sub-par copies also appear in Graystone Industries’ newest advertisement for “Grace,” the commercial deployment of Daniel’s efforts, along with a contestation over image. Daniel quibbles about his virtual image (which is admittedly similar to the one that Joe Adama saw the first time that he entered V world) but doesn’t balk at selling the bigger lie of reunification. (Exploring this, I think, tells us a lot about Daniel and his perception of the world.)

On one level, what Daniel offers is a sort of profane/perverted Grace that is situated firmly in the realm of the material; although it addresses notions of the afterlife and death, it attempts to exert control over them through science. Drawing again from my background in Horror and Science Fiction, we can see that while Daniel’s promise is appealing, we can come back “wrong” (Buffy) or degrade as we continue to be recycled (Aeon Flux). Media warnings aside, I would argue that the allure of Daniel’s Grace is the promise of eternal life but would ultimately be undermined by the program’s fulfillment. In a similar fashion, religion, I think, holds meaning for us because it offers a glimpse of the world beyond but does not force us to contemplate what it would actually be like to live forever without any hope of escaping the mundanity of our lives (Horror, on the other hand, firmly places us in the void of infinity and explores what happens to us once we’ve crossed over to the other side).

Perhaps more importantly, however, the reunited parties in the commercial for Grace reconstitute a family: after panning over a torch bearing two triangles (which, if we ascribe to Dan Brown’s symbology lessons, could represent male/female), we see a husband returned to his wife and children. Needless to say, the similarities between the situation portrayed and Daniel’s own are obvious. On one level, the commercial has a certain poignancy when juxtaposed with Daniel’s low-grade avatar but also subtly reinforces the deeper narrative thread of the family within the episode.

Perhaps more importantly, however, the reunited parties in the commercial for Grace reconstitute a family: after panning over a torch bearing two triangles (which, if we ascribe to Dan Brown’s symbology lessons, could represent male/female), we see a husband returned to his wife and children. Needless to say, the similarities between the situation portrayed and Daniel’s own are obvious. On one level, the commercial has a certain poignancy when juxtaposed with Daniel’s low-grade avatar but also subtly reinforces the deeper narrative thread of the family within the episode.

Picking up on a different representation of the family, classmates also wrote about the contrasting depictions of motherhood as embodied in Mar-Beth andClarice. Although some students focused on the connections between genderroles and parenting, others commented on the divergent views of Mar-Beth and Clarice concerning God and family. One student even mentioned parallels between Clarice and Abraham in order to explore the relationship between the self, the family, and God. Culminating in a post that considers the role of mothers and females in the structure of the family, this succession of blog entries examines family dynamics from the interpersonal level to the metaphysical.

Although we each inevitably respond to different things in these episodes, I believe that there is much to gain by looking at “False Birth” through the lens of the family. For example, what if we look back at a relatively minor (if creepy) scene where Ruth effectively tells Evelyn to sleep with her son? Much like Clarice (and arguably Mar-Beth) is/are the matriarchs of their house, Ruth rules over the Adamas. Since we are exploring gender, let’s contrast these examples with that of the Guatrau, who holds sway over a different type of family—how does Clarice compare with Ruth? Ruth with the Guatrau? How does the organizational structure of the family in each case work with (or against) religion? We often talk about the ability of religion (organized or lived) to provide meaning, to tell us who/what we are, and to develop community—and yet these are also functions of family.

OTHER OBSERVATIONS

-

Hinted at by the inclusion of Atreus, whose story is firmly situated in family in a fashion that would give any modern soap opera a run for its money, we begin to see a pattern as the writers continually reinforce the connections between family and the divine. The short version of this saga is that Atreus’ grandfather cooked and served his son Pelops as a test to the gods (and you thought Clarice was ruthless) and incurs wrath and a curse. After Pelops causes the death of his father-in-law, Atreus and his brother Thyestes murder their step-brother and are banished. In their new home, Atreus becomes king and Thyestes wrests the throne away from Atreus (after previously starting an affair with his wife). In revenge Atreus kills and cooks Thyestes’ son (and taunts him with parts of the body!) and Thyestes eventually has sex with his daughter (Pelopia) in order to produce a son (Aegisthus) who is fated to kill Atreus. Before Atreus dies, however, he fathers Agamemnon and Menelaus, two brothers with their own sordid history that includes marrying sisters (one of whom is the famous Helen). As most of you know, the Trojan war then ensues and Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia; although Iphigenia is happy to die for the war, her mother, Clytemnestra, holds a grudge and sleeps with Aegisthus (remember him?) and eventually kills Agamemnon out of anger. The son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, Orestes, kills his mother in order to avenge his father and, in so doing, becomes one of the first tragic heroes who has to choose between two evils. If we want to take this a step further, we can also examine the resonance between Orestes and Mal from Firefly, to bring it back full circle.

-

The name of Mar-Beth may be an allusion to MacBeth (although it is entirely possible that I am reading too much into this), which is also a story about power, kings, and family. Although I am most familiar with Lady MacBeth and her OCD (obsessed with her guilt, she is compelled to wash invisible blood off of her hands), I would also suggest that Lady MacBeth overlaps with Clarice and the relationship between the MacBeths is similar to that of the Clarice and her husbands.

-

As much as our class does not focus on institutional religion, a background in the Christian concept of Grace provides some interesting insight into Daniel’s project. Although I am not an expert in the subject—I very much defer to Diane—I think that we could make a strong argument for the role of Grace in Christianity and its links to salvation as thematic elements in “False Labor.” Building off of my reaction post, we might think about the role that Grace plays in Daniel’s life and how Joe’s words to Daniel on the landing of the Graystone building speak to exactly this concept.

-

There seems to be an interesting distinction developing between notions of the earth/soil and the air/sky. The Taurons/Halatha, as we have seen before and continue to see in this episode, evidence a strong spiritual connection with the soil (and are also called “Dirteaters”) as Sam utters a prayer before he is about to be executed. We also see the Halatha grumble when the figure of Phaulkon on a television screen, whose name can be associated with flying and the sky. Moreover, in their ways, Daniel and Joe embody this duality as they both show concern for their families but attempt to resolve their issues in different ways–Joe, as is his want, concentrates on the material while Daniel looks toward the intangible.

I’m Dreaming, I’m Tripping over You

I see you.

To see is to dream. To see is to know, to understand, and to accept. To see is to recognize what is still pure and true underneath all of the lies. To see is to unearth all that I have tried to hide, all that is broken and dirty.

To forgive is not to wipe the slate clean; to forgive is not to forget. To forgive is to love in spite of what you know. To forgive is to love because of what you know. To forgive is to love more than you ever thought you could, in the process becoming more than you ever thought you could. To forgive is to truly see.

And to truly see is to look past the facade–the image, the representation–as an inferior copy of who I really am (and maybe it’s not really even me at all). To truly see is to love.

I see you.

The Agony and the Ecstasy

To this day, I still remember the first time that I rejected Gender Studies as a valid area of concern: in college, a friend had joined the Feminist Majority Leadership Alliance and I had declined an invitation to attend. I was, at the time, sympathetic toward women but still too caught up in notions of second wave feminism to identify with a cause in any formal way (well, that and the challenge to the already fragile male ego made joining such an organization an impossibility for me at the time). I am not proud of this moment, but not particularly ashamed either—it was what it was.

How ironic, then, that issues of gender have become one of my primary focuses in media: the representation, construction, configuration, positioning, and subversion of gender is what often excites me about the texts that I study. Primarily rooted in Horror and Science Fiction, I look at archetypes ranging from the Final Girl and New Male (Clover, 1992), to the sympathetic/noble male and predatory lesbian vampires of the 1970s, to the extreme sexualities of the future.

In particular, I enjoy the genres of Horror, Fantasy, and Science Fiction because they allow us to grapple with deeply-seeded thoughts, feelings, and attitudes in ways that we could never confront directly. And, unlike traditional religion, which often attempts to tackle “the big questions” head on, media can provide a space to explore and experiment as we struggle to find the answers that we so desperately seek. The challenge for our students is that so much of American culture is steeped in traditions that reflect underlying aspects of patriarchy; from economics, to religion, to politics and culture, America’s values, thought, and language have been influenced by patriarchal hegemony (King, 1993). All of a sudden, we begin to question what we have been taught and wonder how history has been inscribed by men, afforded privilege to males, restricted the power of the female, and subjugated the female body (Creed, 1993).

In particular, I enjoy the genres of Horror, Fantasy, and Science Fiction because they allow us to grapple with deeply-seeded thoughts, feelings, and attitudes in ways that we could never confront directly. And, unlike traditional religion, which often attempts to tackle “the big questions” head on, media can provide a space to explore and experiment as we struggle to find the answers that we so desperately seek. The challenge for our students is that so much of American culture is steeped in traditions that reflect underlying aspects of patriarchy; from economics, to religion, to politics and culture, America’s values, thought, and language have been influenced by patriarchal hegemony (King, 1993). All of a sudden, we begin to question what we have been taught and wonder how history has been inscribed by men, afforded privilege to males, restricted the power of the female, and subjugated the female body (Creed, 1993).

And, the female body, as a site of contestation, provides a solid point of entry for a discussion of gender issues; gender is inextricably linked with sex—Clover, for example, argues that sex follows gender performance in Horror films (1992)—and also inseparable from discussion of the bodies that manifest and enact issues of gender. Consider how women’s bodies have traditionally been tied to notions of home, family, and reproduction. The basic biological processes inherent to women serve to define them in a way that is inescapable; as opposed to the hardness of men, women are soft, permeable, and oozing. On another level, we are treated to an examination of the female body through depictions of birth gone awry: from Alien, to possession (and its inevitable consequence of female-to-male transformation), to devil spawn, we have been conditioned to understand women as the bearers of the world’s evil.

Issues of birth also raise important notions at the intersection of science, gender, and the occult. Possession movies, in particular, have an odd history of female “victims” that undergo a series of medical tests (evidencing a binary that our class has come to label as Science vs. Magic/Faith) and feature male doctors who typically try to figure out what’s wrong with the female patient—they are literally trying to determine her secret (Burfoot & Lord, 2006). Looking at this theme in a larger context, we reference the Enlightenment (which was previously discussed in our course) and La Specola’s wax models as examples of scientific movements in the 17th century (and again in the 19th century) that sought to wrest secrets from the bodies of women, evidencing a fascination with the miracle of birth and understanding the human (particularly female) body. (La Specola as a public museum had an interesting role in introducing images of the female body into visual culture and into the minds of the public.) Underscoring the presence of wax models is a desire to delve deeper, peeling away the successive layers of the female form in order to “know” her (echoes of this same process can assuredly be found in modern horror films). It seems, then, that the rise of Science has coincided with an increased desire to deconstruct the female body (and, by extension, the female identity).

Issues of birth also raise important notions at the intersection of science, gender, and the occult. Possession movies, in particular, have an odd history of female “victims” that undergo a series of medical tests (evidencing a binary that our class has come to label as Science vs. Magic/Faith) and feature male doctors who typically try to figure out what’s wrong with the female patient—they are literally trying to determine her secret (Burfoot & Lord, 2006). Looking at this theme in a larger context, we reference the Enlightenment (which was previously discussed in our course) and La Specola’s wax models as examples of scientific movements in the 17th century (and again in the 19th century) that sought to wrest secrets from the bodies of women, evidencing a fascination with the miracle of birth and understanding the human (particularly female) body. (La Specola as a public museum had an interesting role in introducing images of the female body into visual culture and into the minds of the public.) Underscoring the presence of wax models is a desire to delve deeper, peeling away the successive layers of the female form in order to “know” her (echoes of this same process can assuredly be found in modern horror films). It seems, then, that the rise of Science has coincided with an increased desire to deconstruct the female body (and, by extension, the female identity).

In similar ways, we saw echoes of this mentality embodied by Daniel Graystone as he struggled to understand Automaton Zoe’s secret earlier in the season. Speaking to a larger ideology of Science/Reason/Logic as the ultimate path to truth (as opposed to emotion/intuition), we again see an example of the female body being probed. And although Automaton Zoe is not a cyborg in the strictest sense of the term, we can understand her as a synthesis of human/machine components–this then allows us to incorporate previous readings on the presence of the female cyborg in Science Fiction.

Given our class’ focus on faith in television, however, we can also consider how female transgression has roots in Christian tradition as demonstrated by the story of Eve (which is also a story about the consequences of female curiosity in line with Pandora and Bluebeard)—how many ways can we keep women in check?